This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Thanks for all the replies to yesterday’s letter. We discuss them below, along with some thoughts on the current bout of market illiquidity. Are we missing something important? Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Return to the market matrix

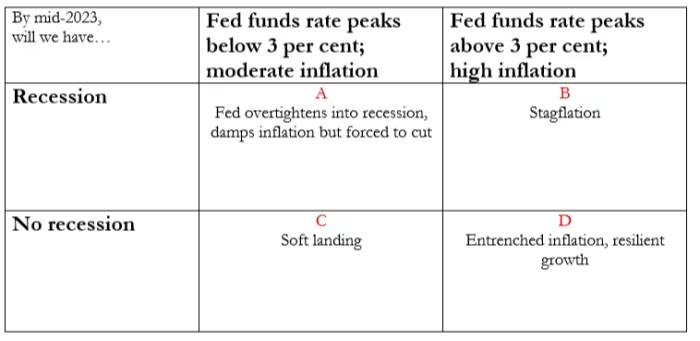

Yesterday we presented this matrix of possible economic scenarios for the next 12 months, and asked readers to weigh in with probabilities and preferred asset classes for each cell:

Anyone who offered hard numerical probabilities is included in the chart below, alongside the Unhedged house opinion:

Mostly everyone seemed in agreement that soft landing (C) and growthflation (D) are lower probability. Readers see a two-in-three chance of recession in the next 12 months. Stagflation (B) was the most divisive cell. Some were completely certain that we are, as reader Todd Foley put it, “on the precipice of a stagflation tsunami”. Others thought it unlikely.

Unhedged tends toward a successful inflation-fighting campaign that sinks us into recession (A). We figure that the Federal Reserve is dug in on bringing down inflation — but both growth and inflation are showing signs of peaking already. The Fed may push on an opening door, hard. Housing inflation will ease as wages continue moderating, and bloated inventories will prove disinflationary. Unfortunately that will spell a recession.

Our friend/nemesis John Authers at Bloomberg offered a probability distribution very much in line with Unhedged readership (in alphabetical order, 40/40/15/5). He thinks inflation is a bigger threat than we do: “I see more of an inflation risk than you do, partly for reasons beyond the Fed’s control.” Oil and food commodity inflation may indeed prove decisive.

What about asset class picks? Here’s ours:

-

A (low inflation and recession): keep it simple and own longish-duration Treasuries.

-

B (stagflation): high-quality, dividend-paying staples stocks for relative price stability and a little return. All assets may perform badly under stagflation, but we’d rather own Pepsi, Johnson & Johnson, Kimberly-Clark, Bristol-Myers et al than sit and watch our cash lose its earnings power. We wish these stocks were cheaper; we can only stand to own so many Treasury inflation-protected securities at zero-ish yields.

-

C (soft landing): equities and corporate credit.

-

D (growthflation): commodities.

Several of our picks overlapped with those of Matthew Klein at The Overshoot. He picked Tips under stagflation; John says buy precious metals.

Readers were even more imaginative. In scenario A, John Clardy notes an out-of-fashion pick that could come back into vogue: emerging market equities. He expects the dollar to weaken, which could help growth in EMs as the US sags. Dominic White at Absolute Strategy Research disagrees. He picks EMs in scenario C instead. Or if the future seems too unsure, Hans Ole Lørup suggests looking for promising growth stocks positioned for decarbonisation.

Several readers proposed buying value stocks as the best all-weather pick. We’re not so sure. Value stocks tend to be cyclical, and get whipped heading into a recession.

Keep sending your probabilities and picks our way. If there’s interest, we’ll keep updating the reader average. There is wisdom in the crowd. (Wu & Armstrong)

A few words in praise of illiquidity

The FT’s Eric Platt, Joe Rennison and Kate Duguid have written a nice piece about falling liquidity in US markets:

Liquidity across US markets is now at its worst level since the early days of the pandemic in 2020 . . . Relatively small deals worth just $50mn could knock the price or prompt a rally in exchange traded funds and index futures contracts that typically trade hands without causing major ripples.

Slowing growth, rising rates, and high inflation don’t support trading volumes. And then there is the old chestnut about post-crisis regulation:

The trading landscape changed dramatically after policymakers in Washington and Brussels sought to safeguard Main Street from Wall Street in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Through a series of regulations introduced over the past 12 years, banks are now required to hold bigger capital cushions to protect their balance sheets against major swings. It has meant banks now hold far fewer assets, like stocks and bonds, making them less nimble at responding to investors’ requests to buy or sell

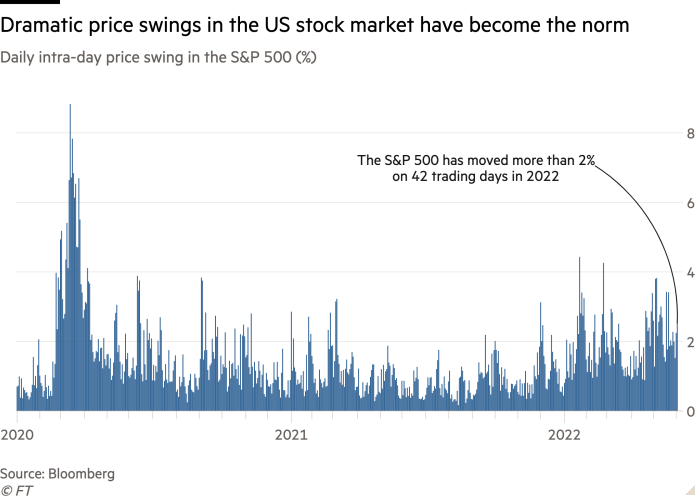

The result has been lot of days where prices swing more than 2 per cent:

Stable prices are nice and we all like being able to trade things when we want to trade them. All else equal, liquidity is good. But all else is not equal, so a few words should be said in praise of illiquidity.

But note, first, that liquidity in the Treasury market is a special case. When the risk-free asset is hard to transact in, the zillions of credit instruments it collateralises and all the balance sheets it anchors become suspect, and bad things happen.

Second, market liquidity (broadly, the ability to trade significant volumes of whatever security without big price disruption) and system liquidity (roughly, how much cash-like stuff there is washing around the financial system) are different (but related) concepts. We blather on quite a bit here about the relationship between system liquidity and asset prices, driven by investors’ preferred allocation to cash and risk assets. Market liquidity and prices are of course related, too. Illiquidity can radically change prices in the short run, but this is different from the portfolio allocation effect.

The reason that silky-smooth market liquidity and low volatility are not an unalloyed good is that they are easily mistaken for, but are not indicative of, the absence of risk. In the hyperliquid low-vol world it is tempting to leverage everything to the hilt and otherwise push the risk envelope, leading to a proper mess when something really goes wrong. The metaphor is forest fires: if you don’t get lots of little ones to clear the underbrush, you get one big one, which kills the trees, too.

There are advantages to a world where institutions must be able to hold the things they buy. The Platt/Rennison/Duguid piece mentions one:

The Vix index, a gauge of volatility in the US stock market, had jumped more than 5 points on a single trading day nine times in the 15 years before the financial crisis. In the 15 years after the crisis, it has happened 68 times. And yet during that period, trading losses incurred by major US banks have been manageable and not threatened the overall financial system. It is a fact not lost on traders and investors, particularly after the fallout from the collapse of family office Archegos last year was broadly contained.

Risk markets exist for two reasons. They let companies raise capital efficiently, and let individuals earn fair risk-adjusted returns on their savings over the long run. Illiquidity is a problem only if it interferes with those two activities. The market does not owe speculators a nice, predictable living.

One good read

Making guns may or may not be an evil business. It is undoubtedly a bad one: commoditised, low growth, and risky.