The pandemic-induced recession is going to go down as one of the most bizarre economic contractions in history.

The National Bureau of Economic Research didn’t officially recognize the start of the recession that began in February 2020 until June of that year.

No one actually needed economic research to tell us we experienced a recession. Everyone knew the same day the NBA postponed its season, Tom Hanks contracted Covid and schools across the country were closed that a recession was at our doorstep.

It’s not always going to be that easy.

For starters, the definition of a recession itself is difficult to pin down. Some people claim its two consecutive negative GDP prints.

NBER has its own definition:

The NBER’s traditional definition of a recession is that it is a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and that lasts more than a few months. The committee’s view is that while each of the three criteria—depth, diffusion, and duration—needs to be met individually to some degree, extreme conditions revealed by one criterion may partially offset weaker indications from another.

Economic data is not like the stock market. It’s not updated every single day. It can be difficult to pin down. It requires estimates, surveys, updates and adjustments.

The U.S. economy is something like $25 trillion consisting of millions of workers and businesses. There are lots of moving pieces so it can be difficult to get a grasp on what’s going on in real-time.

For instance, there was a brief recession that began in January 1980. NBER officially called the January recession start date in June, just a month before the recession was over in July. By the time NBER made it official that the recession ended in July 1980, a new economic contraction was already starting in July 1981.

The recession that lasted from July 1981 until November 1982 wasn’t declared until January 1982.

The recession that began in the summer of 1990 wasn’t determined until the spring of 1991.

The March 2001 recession wasn’t officially called declared by NBER until November 2001, the month it ended.

The Great Financial Crisis recession started in December 2007. It wasn’t made official until December 2008, the same month Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme finally came to light.

The interesting thing this time around is everyone — even Cardi B — seems to be predicting a recession right now.

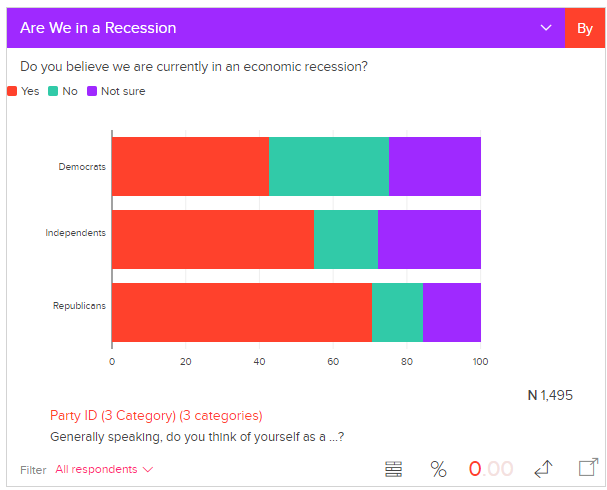

In fact, a lot of people seem to think we’re already in a recession. Just look at these survey results:

Seven out of 10 Republicans think we’re currently in a recession. More than half of all independents and 43% of Democrats think the same.

The unemployment rate is still 3.6%. Wages are rising. Consumers are still spending money like crazy.

We could be in a recession right now but the fact that the U.S. economy added 1.2 million jobs in the past 3 months would seem to counter that argument.

Maybe this is just a poorly worded survey or maybe people really hate inflation.

Yes, inflation is the highest it’s been in 40 years but high inflation does not mean we are currently in an economic slowdown.

However, the possibility of a recession is certainly elevated because inflation is so high at the moment. It’s going to be difficult to bring it back down without causing a recession.

Recessions have caused the majority of the biggest crashes in history so it’s understandable that stock market investors are nervous. The S&P 500 is currently down 14% or so from all-time highs.

Many pundits feel like that’s not bad enough considering the Fed is raising rates and inflation remains elevated.

The stock market could certainly fall further from here but it won’t be easy to use the economy as some sort of signal for stock market performance if we do go into a recession.

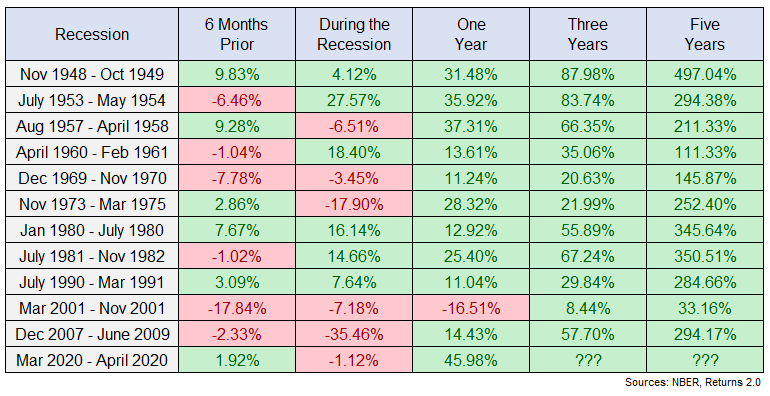

Here is a look at every recession since WWII along with S&P 500 returns in the 6 months leading up to the recession, during the actual recession itself and then one, three and five years from the end of the recession:

The stock market and the economy are not always in sync with one another.

Sometimes the stock market front runs the economy. Sometimes the stock market is too slow to react to economic data. Sometimes stocks fall as the economy is contracting. Sometimes stocks bottom well before the economy does.

Most of the time, the stock market does very well after a recession is over.

The average one, three and five year forward returns for the S&P 500 following a recession are +20.9%, +48.6% and +256.4%, respectively.

That’s pretty good.

Unfortunately, the average recessionary correction since WWII is -31%.

Not good.

We all know about all of the worst-case scenarios for a market crash in this group — 1973-74, the dot-com blow-up, the Great Recession, the Corona Crash, etc.

But what about the best-case scenario for the stock market during a recession?

The 1953-1954 recession caused a drawdown of less than 15% in the stock market. In 1980, the S&P fell just 17%. The 1948-1949 and 1957-1958 recessions saw stocks to fall a little more than 20%. In 1990 it was less than 20%.

So there have been instances when the economy took a step back but the stock market didn’t completely fall apart.

This is what makes investors so anxious right now — things could get way worse or the worst could be behind us. We’ll only know with the benefit of hindsight.

It makes sense to see a stock market decline when the economy slows so I understand the desire to time the market when it seems like a recession is imminent.

The problem here is twofold:

(1) Predicting the timing of a recession is hard to do.

(2) Predicting how and when the stock market will react to a recession is also hard to do.

You could nail the timing of the recession but completely whiff on the bottom of the stock market.

It’s important to remember even if you knew the exact start and end dates of the next recession, it wouldn’t necessarily help you in determining the path of the stock market in the meantime.

Timing the economy is hard.

Timing the stock market is harder.

Further Reading:

The 2 Types of Bear Markets