From all accounts, floating-rate mortgages continue to outsell 5-year fixed terms.

It doesn’t hurt that variables are priced at an average of 184 basis points below 5-year fixed rates.

Come June 22, however, more people will be questioning their faith in variables. That’s when we’ll receive May inflation data, and it should be enough to give over-leveraged borrowers the chills. Economists are calling for a CPI reading of anywhere from 7.1% to 7.5%. That would make it the most menacing inflation print since 1983 when prime rate was 11.5%.

As some second-guess the “variable-rate advantage,” we’ll hear more people asking things like, “Is it too late to lock in?”

But with that 184-basis point fixed-variable spread intact (for now), most will probably conclude that floating rates still have too much of a lead to pass up.

Mortgage spreads aren’t just random

You may have noticed something interesting about the almost-200 bps fixed-variable spread. It’s roughly the same as the degree of rate tightening expected by the bond market.

And that makes sense, if you think about it. “The market is smart and is usually good at setting 5-year [fixed] rates at a level that reflects expectations for future variable-rate movements,” BMO economist Robert Kavcic said in an emailed interview.

As most readers here know, 5-year fixed rates move with 5-year bond yields. Canadian yields are determined by all sorts of factors, but essentially the 5-year yield reflects the average expected Bank of Canada overnight rate over the next half-decade, plus a term premium.

Jargon buster: A term premium is simply the extra yield investors demand for the risk of locking up their money for five years.

That is to say, the bond market—which discounts more information about future rates than we could fathom—is telling us the overnight rate will top out roughly in the mid-3% range.

Is the bond market wrong a lot? Heck, ya. But it’s less wrong than the experts you see on TV or in the papers.

So, if rates are priced efficiently, and if we have a rough sense of where rates will likely end up (based on the best information available), what point is there in trying to forecast which term will be least expensive?

Projecting which mortgage will win over five years “can be hard when the market is priced to reflect expected changes,” Kavcic says. You’re usually better off focusing on factors you know, he says, like the “applicant’s financial situation and tolerance for payment risk.” That includes the borrower’s five-year plan, their prepayment likelihood (given prepayment penalty differences), and so on.

The urge to float

If you have to lean one way or the other, consider this. Prime rate should be almost double its post-pandemic low within six to nine months. The only time in history when variable rates under-performed 5-year fixed rates after prime was over 30% above its five-year average was during a short stretch in 1979.

In other words, rates are cyclical because the economy is cyclical. As a result, prime rate usually reverts (lower) to its mean after being significantly above average.

But, if you’re going to try and out-guess the market and favour a short-term fixed or variable, it means one thing. You’re facing the chance we’ll see an exception, as we did in 1979.

If you go that route, know that exceptions can be painful. The 1979 case saw rates run up 1000 basis points in people’s faces after the “experts” told them to renew into 1-year fixed terms. Given Canadians are over twice as sensitive to rates today (source: CIBC’s Benjamin Tal), emergency hikes probably wouldn’t exceed half that. But even a 500-bps hiking cycle would still wreak financial devastation.

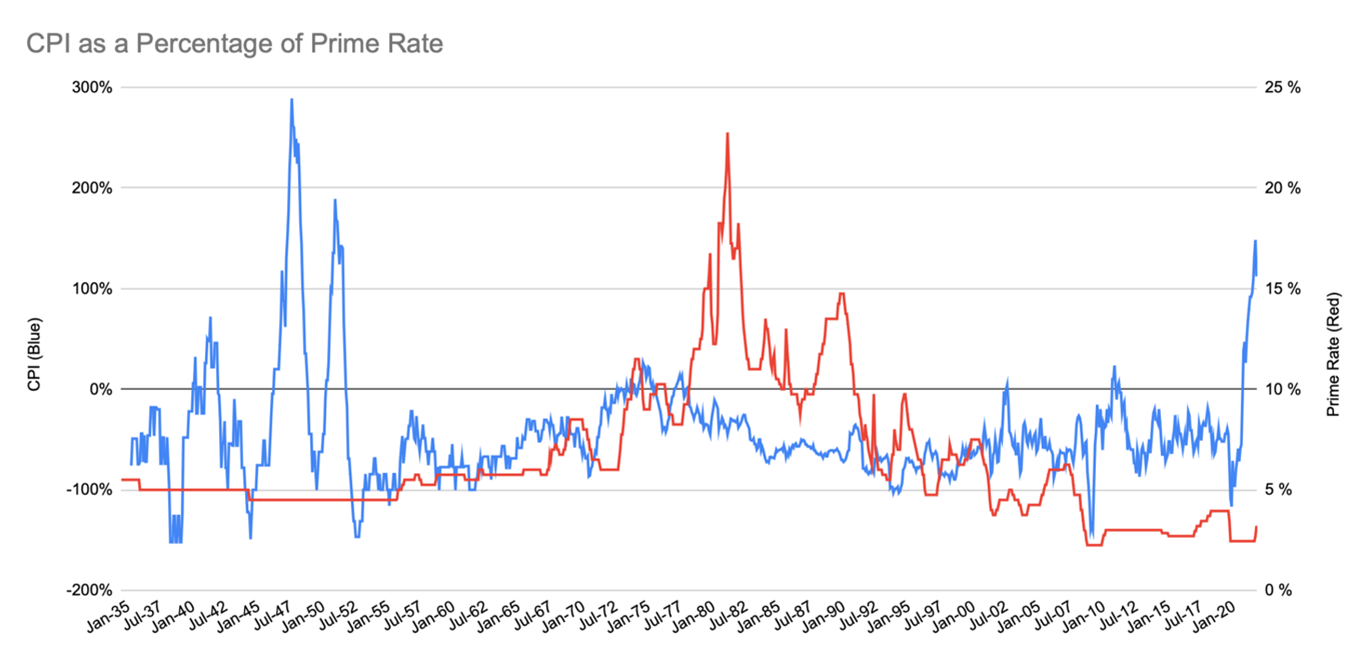

Fast-forward to 2022, and inflation is once again dramatically above prime rate to a degree we haven’t seen since the 1950s. The blue line (CPI) in the chart above shows how far from the barn the horse has run.

If you buy into the argument that Canadians are over-leveraged, and therefore rates can’t go up significantly, remember that magnitude is only one factor. Duration matters too, and high rates could stay with us longer than expected, especially if there’s another inflation shock from Russia, China, oil or pandemic waves #5, 6, 7….

The fact that inflation could persist longer than anticipated—thanks to the historic detachment of inflation expectations, high energy prices and trade disruptions—means there’s a chance that market rate expectations are too low.

Sage mortgage professionals know that the future likes to surprise people. They don’t try to guess future rates or over-rely on historical research that may not currently apply. They use forward rates only as a guide to potential rate risk and where we might be in the business cycle. Job #1 remains recommending suitable products based on what’s known about the borrower.

One product solution

That brings us back to Robert Kavcic’s point about rate market efficiency. If we resign ourselves to the fact we’re no smarter than the market, and that the market has fairly priced both 5-year fixed and variable terms, then having both fixed and variable exposure would seem logical to avoid a guessing game.

That’s precisely why diversified risk products—i.e., hybrid (part fixed / part variable) mortgages—exist. A hybrid simultaneously protects against the risk rates may have to rise significantly, while offering the chance to overweight in a variable when appropriate (e.g., a 65/35 variable/fixed split) to potentially take advantage of cyclical peaks.

And, despite my rule of thumb about not mixing term lengths in a hybrid, this case could warrant mixing in a cheaper 3- or 4-year fixed with the variable instead of a 5-year in the 5% range. When the shorter term comes up from renewal, there will be options at that time.

Of course, once core inflation starts making relative lows (plural, not just one down-tick) and once the OIS market starts pricing in rate cuts 12-18 months out, a borrower’s variable exposure can be more safely increased, potentially up to 100% depending on their circumstances.

Rate data source: MortgageLogic.news.