At a Senate hearing this week Jerome Powell was asked about balancing the Fed’s duel-mandate of price stability and maximum employment.

Powell said, “Right now the labor market is extremely tight and I would say unsustainably hot. And there is a mismatch between supply and demand there.”

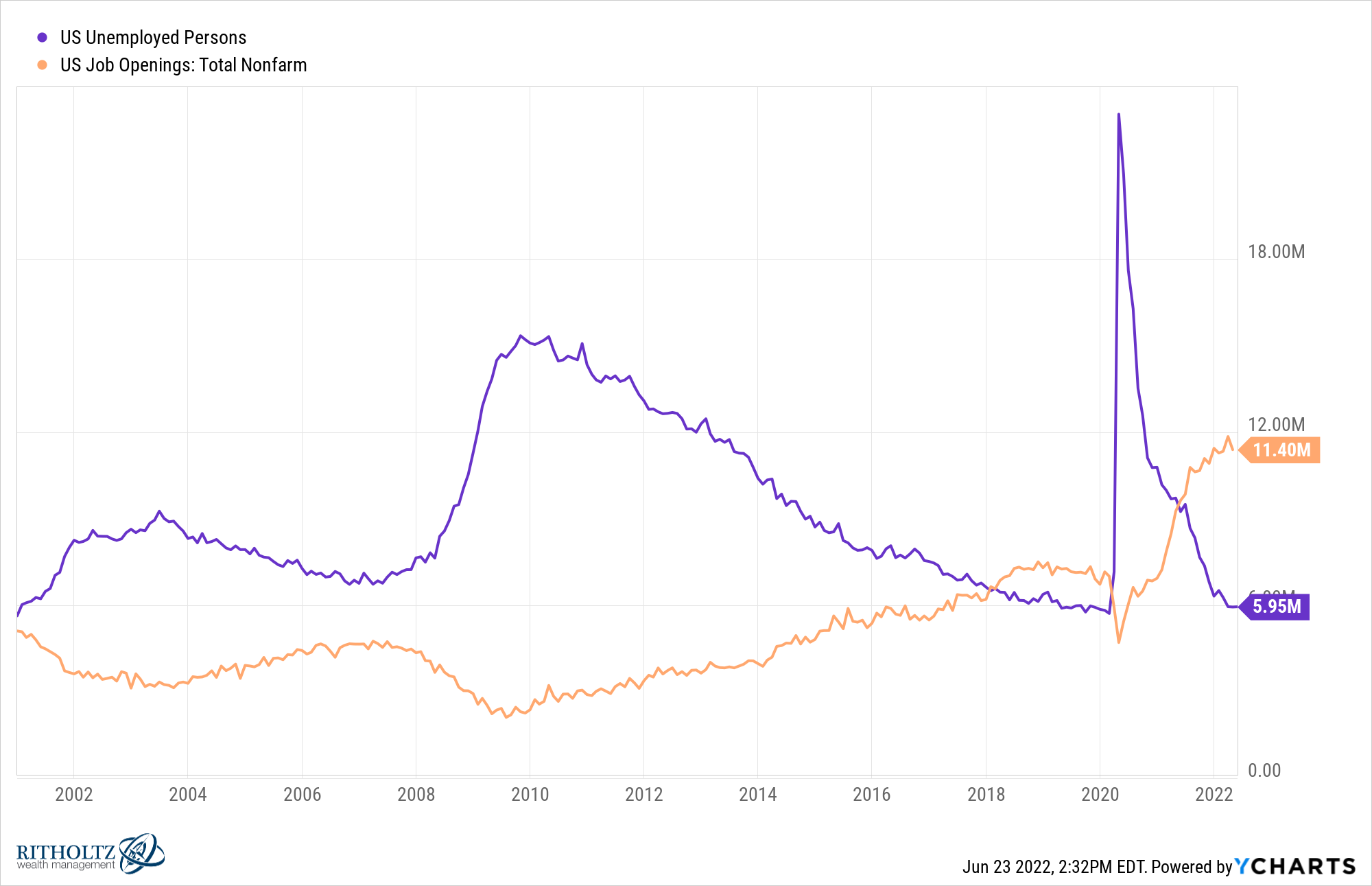

I’ve used this chart before but it bears reposting:

There are two jobs available in this country for every one person who is unemployed and looking for work.

I would say that constitutes a supply and demand mismatch.

We’ve never seen anything like this so Powell’s description of the labor market as unsustainably hot makes sense.

The fact that the labor market is so hot is one of the main reasons the Fed is focusing so much attention on the price stability component of its duel mandate.

By raising interest rates the Fed is hoping to slow demand but also cool the jobs market to temper inflation.

Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers said this week that the unemployment rate needs to be above 5% to contain inflation:

We need five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation — in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment.

I’m sure Summers is using some sort of economic formula to come up with this level but all you have to do is look back at history to see what happens when the unemployment rate rises.

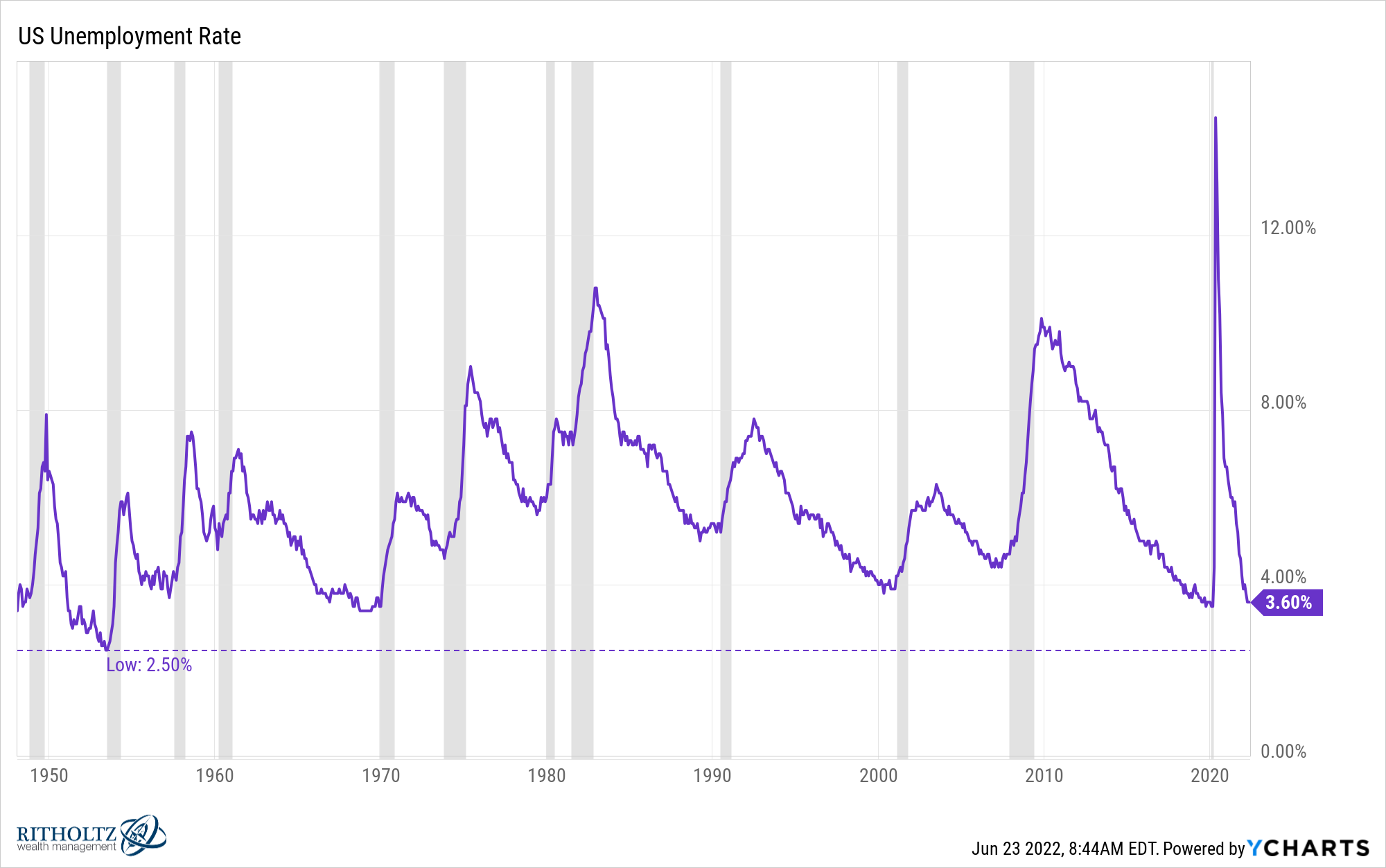

Here’s the unemployment rate going back to the late-1940s:

When the unemployment rate comes off a low it always goes much higher. This makes sense when you consider those spikes are caused by a recession in every instance.

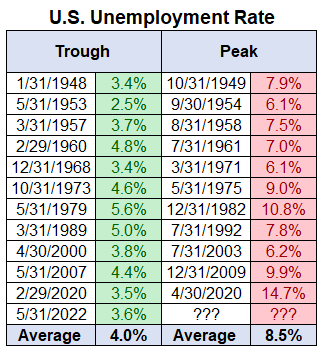

Here are the lows and highs from every cycle:

The lowest unemployment rate in modern times was 2.5% in the early-1950s. That was also the lowest high the unemployment rate has ever seen following a recession at 6.1%.

The average increase in the unemployment rate is more than 4%. On average, the unemployment rate doubles when it goes up during an economic slowdown.

While the unemployment rate hasn’t started going up just yet, all sorts of other rates have already moved higher.

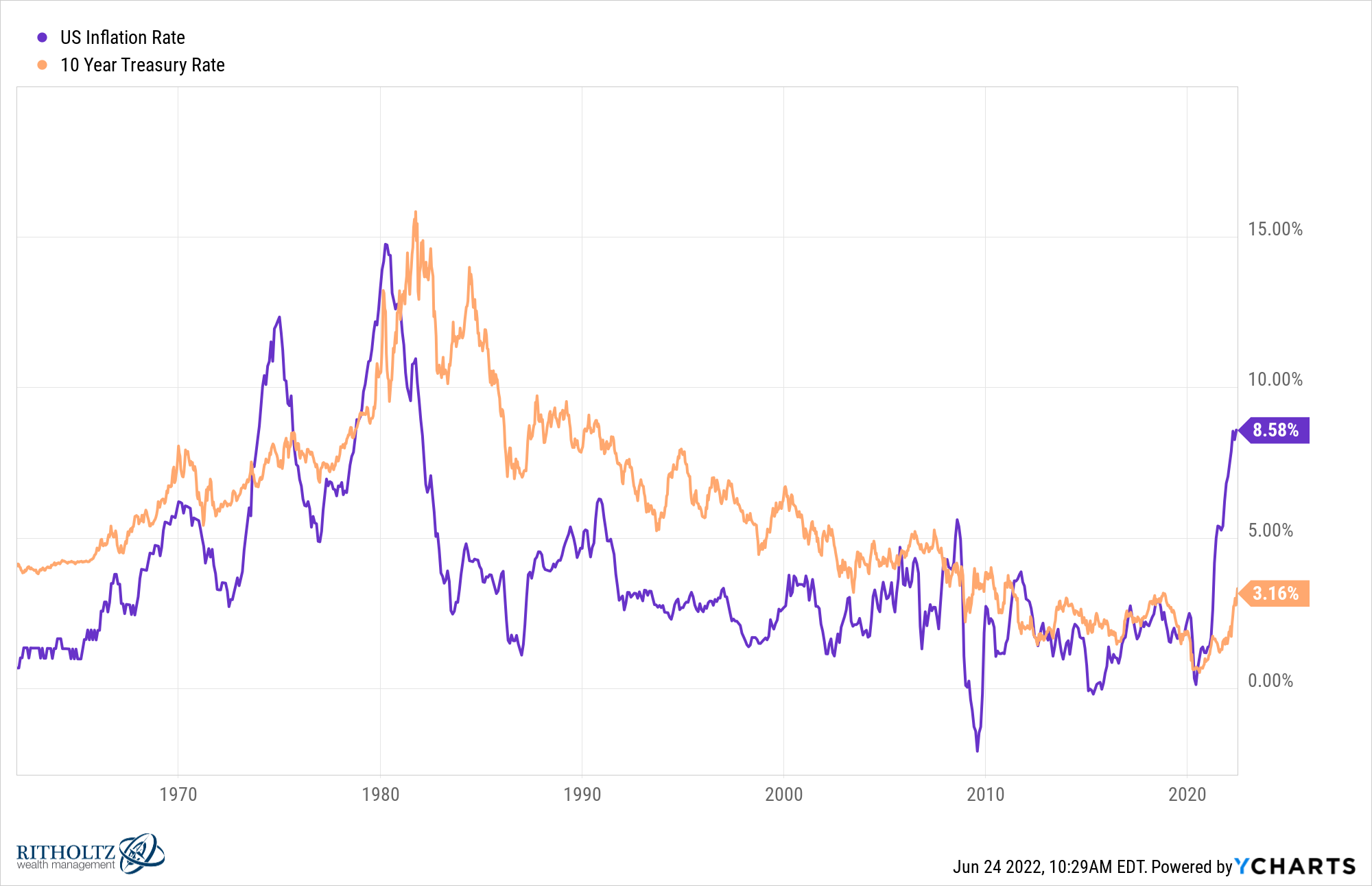

Everyone already knows the inflation rate has shot up but that’s bringing up bond yields too. The only other time inflation was this much higher than 10 year treasury yields was in the mid-1970s:

In fact, from 1981 to 2005, the inflation rate was never higher than U.S. government bond yields.

The thing you have to understand about interest rates is that while they generally move in the same direction, they don’t do so at the same magnitude.

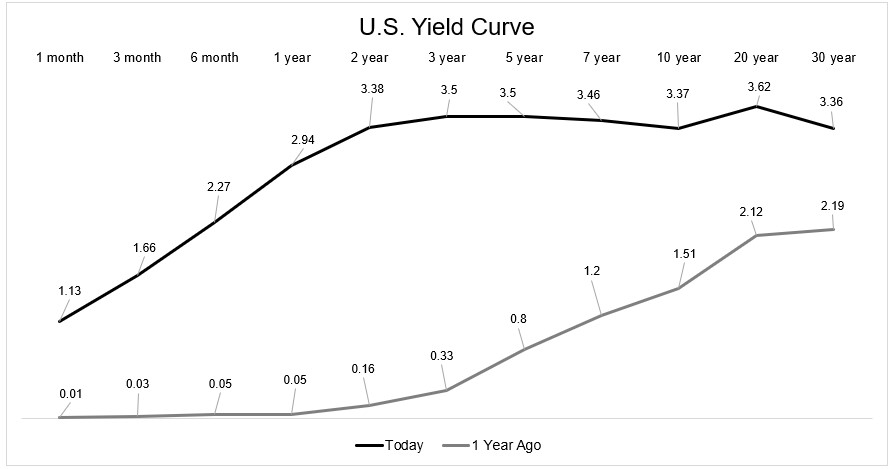

Last week Michael plotted out the one year rate change across the treasury yield curve:

The one month to 3 year bonds have seen appreciably higher increases than the 20 or 30 year yields.

Unfortunately for consumers of debt, interest rates for borrowing are moving up much faster as well.

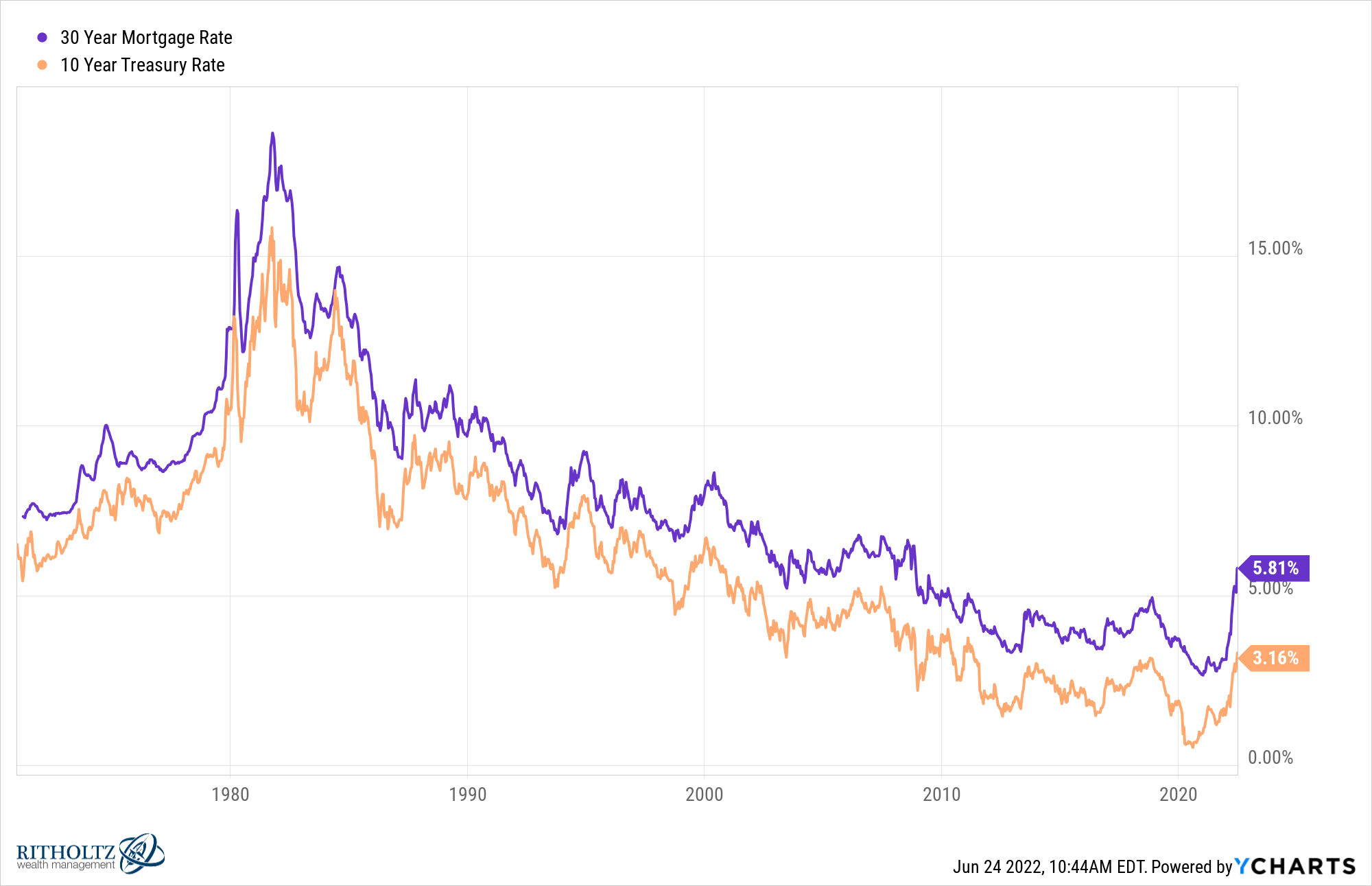

The 30 year fixed rate mortgage tends to track the 10 year treasury yield fairly closely:

This is a good thing for future bond returns but a bad thing for current borrowers.

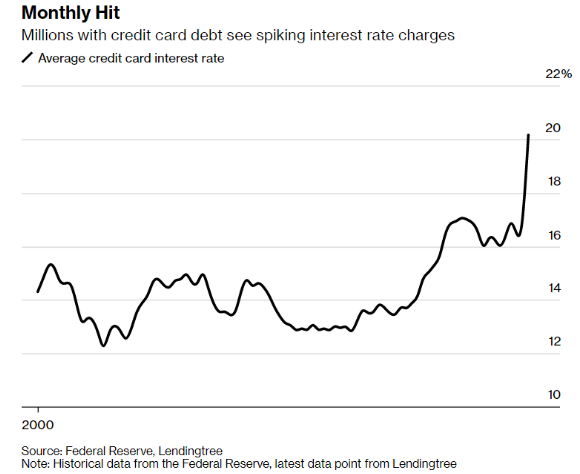

This is especially true of credit card borrowers. Just look at how high those rates have shot up:

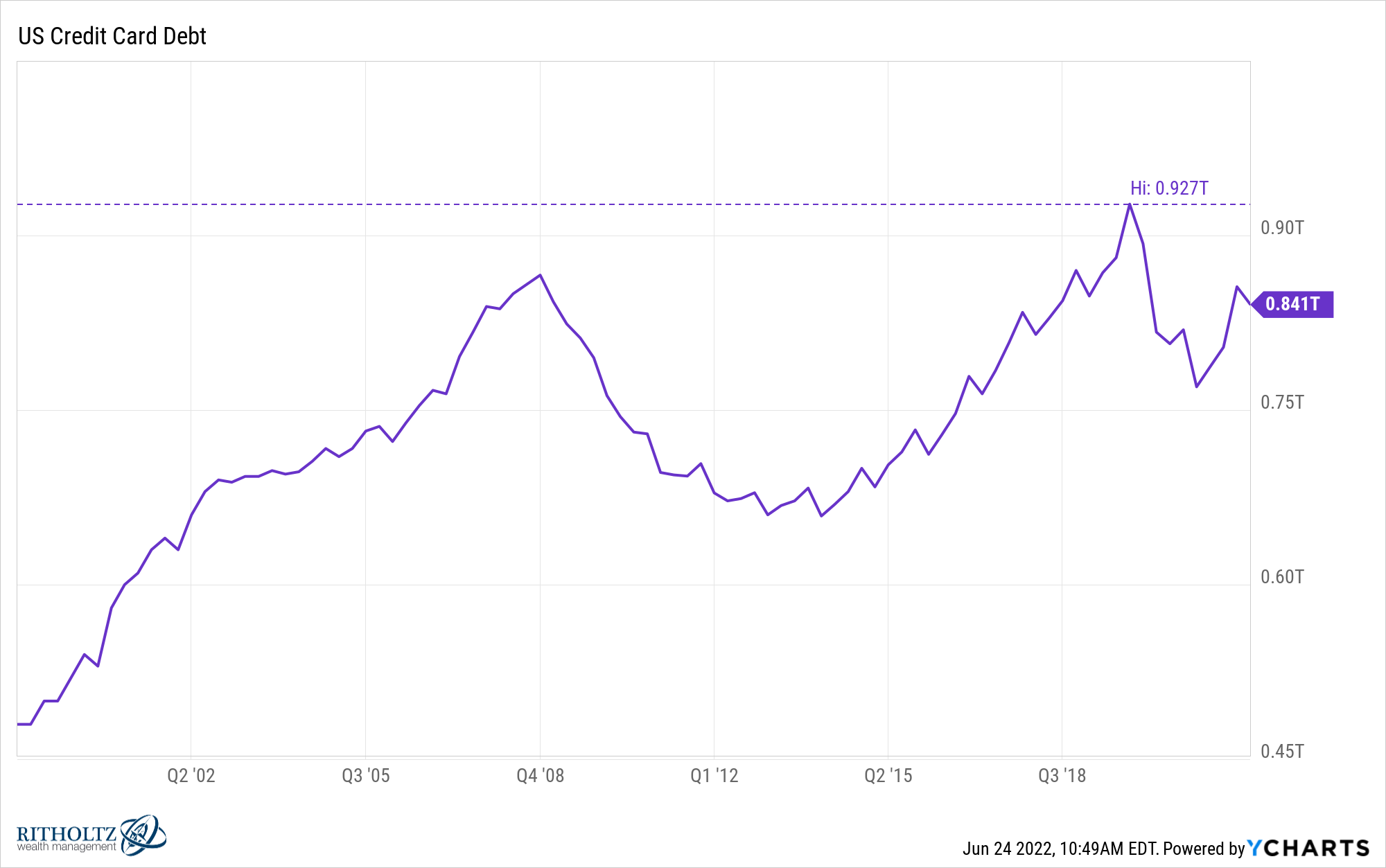

The good news is many borrowers used the pandemic as a chance to pay down their credit card debt. Total credit card debt in the U.S. is still lower than it was pre-pandemic:

The bad news is that those who still hold that debt and don’t pay off their balance every month are now going to be in trouble.

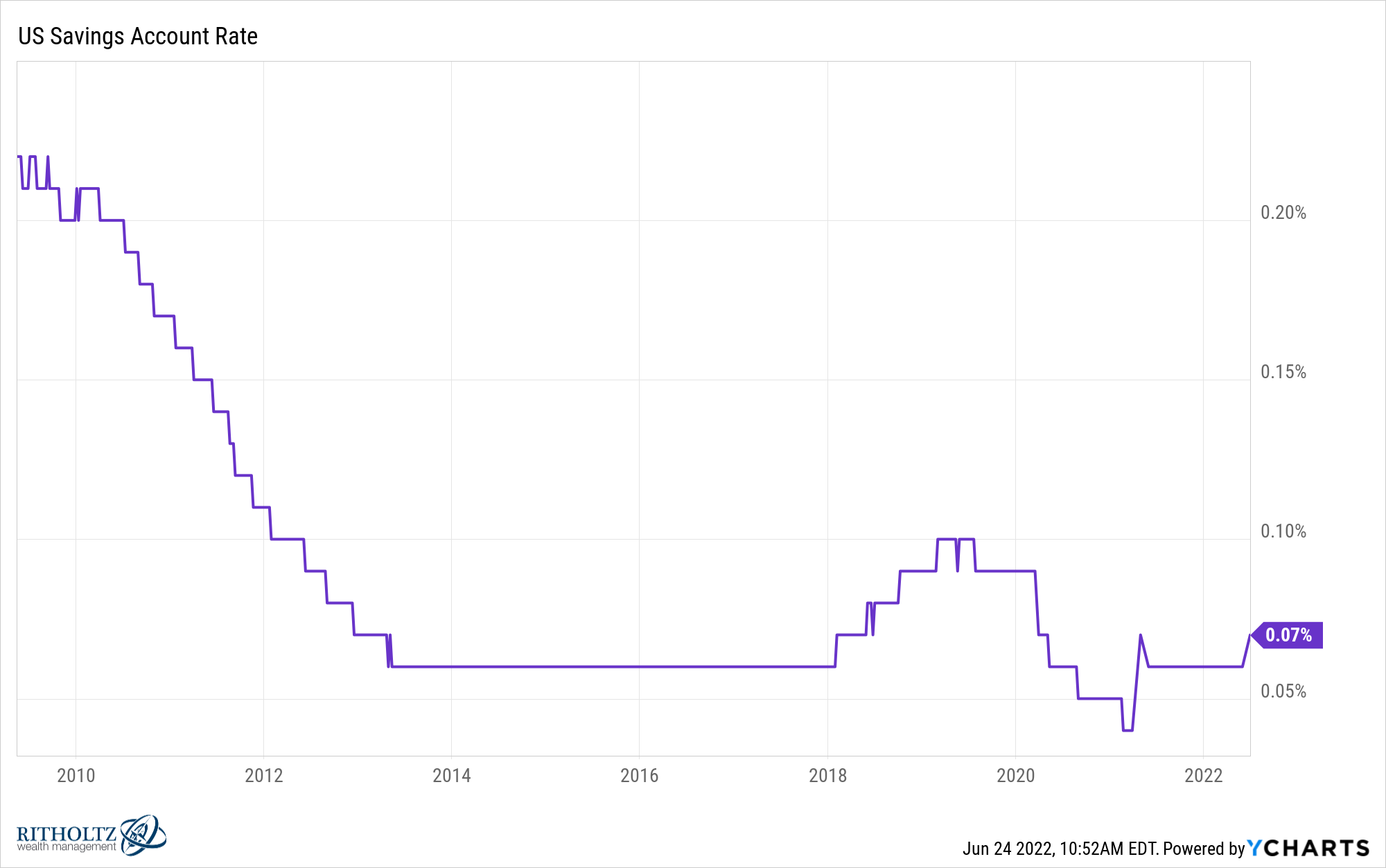

Contrast credit card rates going from 16% and change to more than 20% in the blink of an eye with the average savings account yield at brick and mortar banks:

You might have to squint to see it.

Seven basis points!

Obviously, you can earn more money in an online savings account but those rates are nothing to write home about just yet. I use Marcus and they finally raised their yields to 1% this week.

It’s funny how quickly the banks will raise borrowing rates for things like mortgages and credit cards but move at a sloth’s pace when adjusting savings account yields.

Michael and I spoke about all of these rates and much more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Interest Rates Are Getting Weird

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately: