This article is an on-site version of our Trade Secrets newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every Monday

Hello and welcome to Trade Secrets. If you’ve not noticed it, there’s a G7 heads of government summit going on in the Bavarian mountains today. Among other things, the leaders formally launched a supposed $600bn plan for infrastructure and investment to challenge China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which sounds like yet another iteration of the stuff we’ve been hearing for several years. Today’s main piece looks at the latest of an array of shocks to the world trading system — a high-inflationary environment and the rising risk of recessions — and whether this will be the one that finally sends globalisation into long-term retreat. Regular readers won’t be astounded to hear that I remain quite optimistic it won’t. If you think I’m wrong about that or anything else and want to let me know about it, I’m on alan.beattie@ft.com. Charted waters looks at the food crisis fuelled by conflict in Ukraine.

Get in touch. Email me at alan.beattie@ft.com

Supply shocks haven’t worked, let’s try demand

It’s quite honestly like a gang of malicious economists (that is, economists) have taken a fairly well-functioning global goods trading system and repeatedly bashed it hard in quick succession from a variety of angles just to see whether it falls over.

In 2020 we got the negative shock to goods production and demand from the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. Then through most of 2021 the demand bit reversed and there was a massive resurgence of consumer durables sales and hence trade volumes, putting pressure on sclerotic ports. Demand for consumer goods also created upstream supply problems such as shortages of semiconductors.

In late 2021 the Omicron wave brought a fresh negative supply shock to production, especially in China. The Russian invasion in Ukraine has since created a whole new container-load of effects: an initial negative supply shock to shipping from blocking Russian ports and ships, a second upward push to freight costs from higher fuel prices and a rupturing of global food markets from the disruption of grain shipments in the Black Sea.

Now, with the global rise in energy prices and inflation comes a potentially hefty negative macro shock from falling real incomes and higher interest rates, and we’re all worrying about the bullwhip effect amplifying consumer demand disruptions up the supply chain. Since goods trade is historically more volatile than gross domestic product, recessions in the big economies could cause a serious contraction in cross-border commerce.

Ralf Belusa, managing director for digital business and transformation at the German-based global container shipping group Hapag-Lloyd, summed it up at a recent FT event: “Our reality today is based on increased, accelerating and interconnected volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity.” A cheery thought.

The various effects of all of this so far has been as follows. Volumes of goods trade have held up pretty well: they’ve pulled back a bit in the past few months, but there’s little sign of a collapse yet. The surge in consumer demand for goods relative to services that followed the first wave of Covid is still largely in place. Flexport, the freight forwarding and supply chain company, says that its measure of preference for goods is tracking back only slowly to 2020 values.

Freight rates have similarly been drifting down, though from historically very elevated levels. Port congestion, which last year was particularly a US west coast phenomenon — Ryan Peterson, chief executive of Flexport, repeatedly compared the underinvested Long Beach/Los Angeles unfavourably with Rotterdam — is also affecting Europe. The first of what could be a wave of dock strikes in Hamburg and elsewhere isn’t helping.

The threat: a new negative global demand shock on top of existing supply disruptions causing a big crunch in trade later in the year or in 2023 and inflicting longer-term damage. The first is a distinct possibility, noted by CEOs as well as macroeconomists. Although the combination of high volumes and freight rates means shipping companies (including bulk carriers bringing fuel and food over longer distances to replace the Black Sea supply) have been coining it in, companies such as Maersk are warning about weakening demand in the second half of the year.

On the other hand, a cyclical correction, even an abrupt one, doesn’t necessarily mean a trend reversal. What with energy shocks and high inflation there are lots of references to the 1970s kicking about. But though there were cyclical movements back then, they didn’t reverse the long-term postwar increase in global trade, despite the collapse of the postwar Bretton Woods trading system in 1971.

And here’s the thing: despite shipping companies worrying about the short term, they are putting big bets on the future. Maersk is warning about the next few quarters, but it is bullish for the longer term. The ratio of new container ships ordered to the existing global fleet is heading to more than 30 per cent for the first time in almost a decade. The companies may be way too optimistic, obviously — there’s a long history of overcorrections in the shipping industry and there was serious overcapacity in 2020 before the pandemic hit. And of course shipping owners are not publicly going to predict a collapse in demand for their services. But still, it’s striking that such huge bets are being taken on global goods trade powering ahead in years to come.

Esben Poulsson, chair of the International Chamber of Shipping, told a recent FT event: “Those owners are investing in new ships in the belief that free trade is here to stay, despite talk of reshoring. I don’t see evidence of [the end of globalisation]. I see a lot of political posturing about it.” Until I’m shown some pretty chunky evidence otherwise, that remains my view too.

As well as this newsletter, I write a Trade Secrets column for FT.com every Wednesday. Click here to read the latest, and visit ft.com/trade-secrets to see all my columns and previous newsletters.

Charted waters

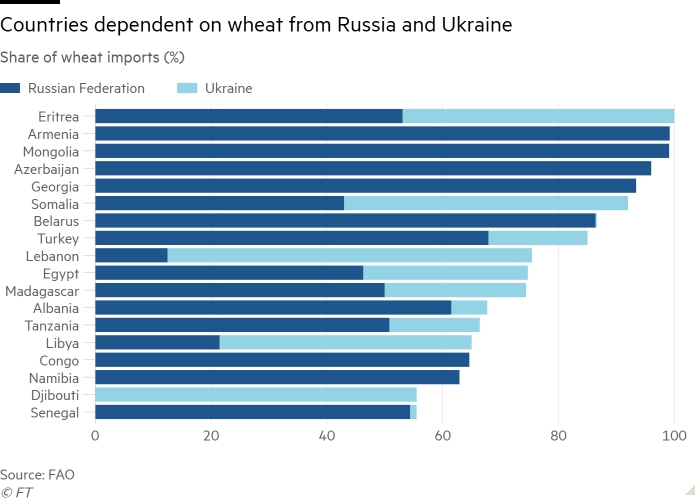

The unfolding food crisis is a key issue of concern for the G7 heads of state meeting today in Germany. But in other parts of the world — notably Africa — it is a real and present catastrophe, as my colleagues Andres Schipani and Emiko Terazono explain. Today’s chart shows how many African nations are reliant on imports of grain from Russia and Ukraine — Eritrea topping the list.

This breakdown in trade caused by conflict in Europe is not the only reason the struggle to eat has become acute in several African nations. The worst drought in four decades across northern Kenya, Somalia and large parts of Ethiopia will mean that up to 20mn people could go hungry in that region this year, according to the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organization. Tragically, further problems are likely to occur as food shortages fuel conflict within the region. (Jonathan Moules)

Trade links

The news service Borderlex explains that the Energy Charter Treaty, accused of exposing governments to expensive litigation if they shift to renewable energy, has been reformed, though it remains to be seen whether enough has been done to placate critics in the EU in particular.

The Essential Goods Monitoring Initiative reports that governments have (sensibly) been cutting import restrictions on food and fertiliser in response to soaring prices.

Three analysts from the Brookings Institution look at the need for the US to attract and admit skilled immigrants if its attempt to expand its domestic semiconductor industry is going to work.

Sam Lowe’s Most-Favoured Nation newsletter (£ but free trial) looks at the UK government getting itself into a tangle by overriding its own trade defence authorities to keep import safeguards on Chinese steel.

An online exhibition of photographs of trade diplomats at the recent WTO ministerial negotiations shows the human stories behind the bureaucracy.

Trade Secrets is edited by Jonathan Moules