The writer is global chief economist at Morgan Stanley

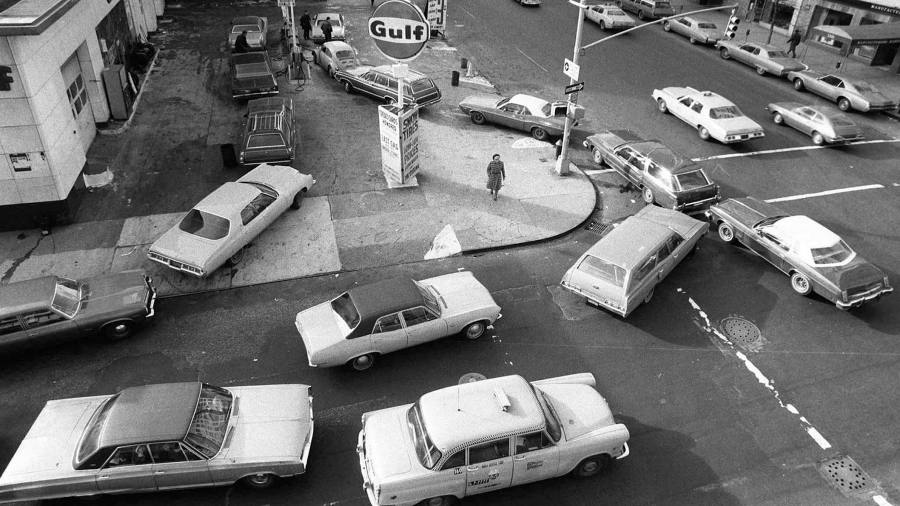

Easy monetary policy, expansionary fiscal policy, rising inflation and then a surge in oil prices — it is very difficult to resist the temptation to draw parallels with the 1970s.

I suggest, however, that the current circumstances are not a repeat of that decade, doomed to end in a deep, policy-induced recession that drags much of the world down. There are several meaningful reasons why today is not yesterday. That said, even if we are not reliving the 1970s, neither are we on an easy path.

In the latter half of the 1960s, the US economy grew ever tighter with stimulative fiscal and monetary policy. The first oil price shock in the early 1970s further ignited inflation. So far, so good as a comparison with today, but the differences quickly become apparent.

The economy’s dependency on oil is substantially smaller now than it was in 1970 — in no small part because services now account for a much larger share of gross domestic product. Indeed, with the US having become the world’s largest oil producer, there is actually now a boost to at least one part of the economy.

Of course, inflation is the percentage change in prices and, viewed through that lens, today’s oil price shocks are not remotely close to what they were five decades ago.

At the end of 2019, just before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, oil was in the neighbourhood of $60 a barrel; it is now roughly double that price. In 1970, West Texas Intermediate, the benchmark for American oil, was running at just over $3 a barrel. In 1974, after the first steep rise in inflation, it had moved to over $10 a barrel — a tripling in the price. By 1980, it approached $40 a barrel, or more than 10 times as expensive as at the onset. A doubling in oil prices is a lot; increasing by an order of magnitude is something completely different.

In the 1960s, inflation began broadly based, with prices of both goods and services rising. Last year, inflation started narrowly, with consumer goods demand soaring as global supply was unable to keep up in the face of a sclerotic supply chain held back by the coronavirus pandemic.

By now, of course, inflation has spread across all categories in the consumer price index, but goods inflation looks ready to bid a retreat. Consider recent earnings reports from retailers who are overstocked and trying to unload inventory. Overspending on consumer goods seems about to correct, and with it, at least some portion of the inflationary pressures.

Nevertheless, the current breadth of inflation cannot be denied, and one fear from the 1970s is that it may become entrenched in the economy. And indeed, some of the longer-term measures of inflation expectations are now starting to rise.

FT survey: How are you handling higher inflation?

We are exploring the impact of rising living costs on people around the world and want to hear from readers about what you are doing to combat costs. Tell us via a short survey.

But consider the following: in 1970, anyone 40 or older had already seen three episodes of inflation comparable to that of the present day. Today’s 40-year-olds have seen nothing comparable, and in fact are more familiar with deflationary trends than inflationary ones.

In 1970, the thought must have been, “Here we go again”, whereas today the question is, “What is next?”

Ultimately, former Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker famously began to wring a decade’s worth of inflation out of the US economy in 1979 by sharply raising interest rates and inducing a recession. (I am happy to leave aside the semantics of whether the Fed raised interest rates or merely restricted money growth; that is a difference with no distinction in this case.)

But by that time, there had been a decade of high inflation, deeply embedded in the mindset of businesses and households that were already all too familiar with high inflation. The effort required to break that cycle was very different to what is needed to rein in today’s excesses.

And that point leads to perhaps the biggest difference of all. We can learn from history if we choose to.

Reams of paper have been filled explaining how and why the “Great Inflation” took root but, in all of the analysis, too-easy monetary policy figures prominently. Current Fed chair Jay Powell witnessed the cost of the Volcker disinflation and has already started to tighten policy meaningfully. To be sure, Powell will need skill, resolve and not a little luck, but — in stark comparison with Volcker’s predecessor, G William Miller — he knows what happens if high inflation is left unattended.

But even if I am right that we are not living a rerun of the 1970s, the path ahead is not rosy. Inflation is undeniably very high, and a large portion of it is in core services, driven by an economy that is trying to buy far more than can be comfortably produced.

Any empirical estimates of how much slack must be engendered in the economy to bring down structural inflation present a very unpleasant trade-off. Either the Fed can bring inflation down quickly by causing a meaningful recession, though likely one that is milder than in 1979, or it can slow the economy to just shy of a recession, but live with elevated inflation for the next few years. Judging from the forecasts the members of the Federal Open Market Committee made at their most recent meeting, they have chosen the latter path. But, as I noted, luck will play a role as well.