After the strong performance run of growth versus value investing in recent years, many investors have started to question the validity of the latter investment style, particularly after the most recent few months. Value stocks underperformed when the markets were on the way down in March, and they’re lagging other investments with the markets on the way up.

Through many discussions I’ve had with the diligent value disciples out there, I can see that their patience is starting to run thin. The centerpieces of the value argument are attractive valuations and mean reversion—the theory that asset prices and returns will revert to their historical averages. Yet many market participants are finding it increasingly difficult to stomach the disparity in performance between growth and value investing, which continues to grow by the day, quarter, and year. To the value diehards, though, the answer is simple: mean reversion has worked in the past, overcoming periods of volatility, and this market environment is no different. They say patience is the answer, because the value premium will always exist.

The Value Premium Argument

The value premium argument has been forever linked to Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, two academics who published a groundbreaking study in 1992 stating that value and size of market capitalization play a part in describing differences in a company’s returns. According to this theory, Fama and French suggested that portfolios investing in smaller companies and companies with low price-to-book values should outperform a market-weighted portfolio over time. The purpose of this approach is to capture what are commonly referred to as the “value” and “small-cap” premiums.

“Value” can be defined as the ratio between a company’s book value and market price. The value premium refers to returns in excess of the market price. The small-cap premium refers to the higher return expected from a company with low market value versus that of a company with large capitalization and high market value.

Value Versus Growth

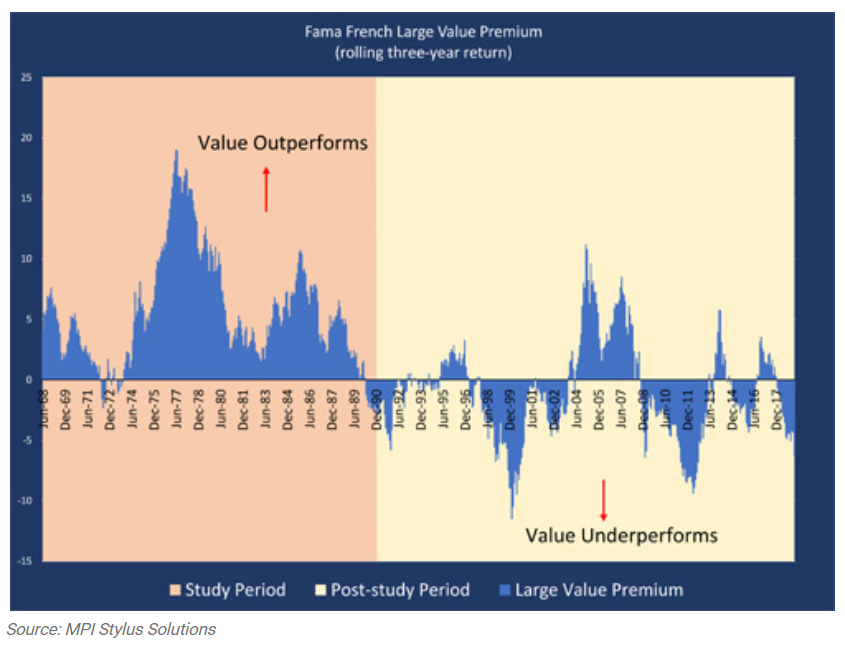

The pink-shaded area in the figure below shows the performance of the value premium (with value outperforming growth) over the study period from 1963 to December 1990 on a rolling three-year basis. Data from the post–study period of January 1991 until the present is shown in the yellow-shaded background.

Note that there are two very different return patterns pre- and post-study. In the pre-study period, value outperformed growth 92 percent of the time, and this data was the basis for the 1992 study’s findings. In the post-study period of the past 30 years, however, growth outperformed value 64 percent of the time. The longest stretch of value outperformance in the past 30 years came during the economic and commodity boom of 2000 to 2008. In other years, the value premium has been largely nonexistent.

Does the Value Premium Still Exist?

In January 2020, Fama and French published an update of their work titled “The Value Premium.” In this report, the two authors revisit the findings from their original study, which was based on nearly 30 years of data that clearly showed the existence of a large value premium. In it they acknowledge that value premiums in the post-study period are rather weak and do fall from the first half of the study to the second. It’s also notable that other studies have come out over the years making similar claims (Schwert, 2003; Linnainmaa and Roberts, 2018).

What can we take away from the data presented by Fama and French? To me, it seems reasonable to ask, if the roughly 30 years of pre-study data was sufficient to conclude that the value premium existed, is not the 30-year post-study period (during which value clearly underperformed) enough time to suggest the value premium has diminished or no longer exists?

When considering this data, investors may wish to question whether mean reversion should continue to be a centerpiece in the value-growth debate. They might also ask whether strategically allocating portfolios to capture a seemingly diminishing premium makes sense. According to the data, we have a few reasons to consider why growth might become the dominant asset class for many investors. When doing so, however, it’s important to keep in mind the potential risks of growth stocks, which may be susceptible to big price swings.

All this makes value versus growth an interesting topic, which I will address further in a future post for this blog. In the meantime, if you’d like to engage in a conversation about value versus growth, please comment in the box below. I’ll be happy to share my thoughts and perspective.

Editor’s Note: The original version of this article appeared on the Independent Market Observer.