Executive Summary

Advisors occasionally encounter situations where their recommendations conflict with a prospect’s or a client’s opinions or beliefs. When encountering this resistance, the advisor has a choice to make: either to alter their recommendation to make it more acceptable to the client’s way of thinking, or to dig in and attempt to change the client’s mind on the subject (or, in the most extreme cases where the difference cannot be resolved, to re-evaluate the engagement and perhaps end it altogether).

In some cases, it is clear to advisors that it would be inappropriate to try to persuade a client to go against their values. For example, when a client and advisor are divided on a subject stemming from the client’s religious beliefs (e.g., a client who is requesting to use Shariah-compliant funds), few advisors are going to try and talk a client out of those beliefs. And if the advisor is not familiar enough with such religious funds to advise on, the advisor may simply refer the client out to another advisor who is a better fit. But in other cases, such as when a prospect or client wants to follow the advice of a popular financial guru, the advisor may be more tempted to push back.

For advisors in this situation, the Japanese martial art aikido can provide perspective on how to respond. In aikido, rather than fighting or resisting an attack, a defender redirects the attacker’s energy, rendering it harmless. Likewise, when advisors receive pushback from clients which they feel could be harmful to the client if carried out, rather than arguing or persuading the client to change their mind, it may be helpful instead to think about how they could redirect that energy in a harmless (or even beneficial) direction.

While many financial advisors may disagree with the opinions espoused by pundits like Dave Ramsey and others (e.g., their views on asset allocation or paying down debt), nonexperts often find them very compelling. Furthermore, in some cases, following the advice of a financial guru might have had a real positive impact on a client’s life – meaning that, for the advisor, convincing a client to simply ignore a popular pundit’s advice and start following the advisor’s (possibly conflicting) recommendations might be a difficult and even unrealistic proposition for the client.

Advisors in this situation can consider using the lessons of aikido. Instead of trying to change their clients’ beliefs, it may be possible to channel them in a more productive manner. For example, if a client wants to follow a pundit’s asset allocation advice, an advisor could – rather than taking a hard line – try to see what it is about the pundit’s advice that appeals to the client, and then construct a portfolio that aligns with those values (while still being sound from the advisor’s perspective).

From this perspective, building the portfolio becomes an exercise that is similar to any other values-based investment philosophy (e.g., Socially Responsible Investing). In order to best align with the client’s values, the advisor may need to operate from a slightly limited fund universe – which, despite not being 100% optimized from the advisor’s perspective, can still be a worthwhile compromise as a way to build a portfolio that aligns with a client’s bigger-picture values (and that they, therefore, may be more likely to stick with in the long run).

Ultimately, the key point is that for financial advisors, understanding and appreciating a client’s values can make all the difference between working with an engaged and enthusiastic client, and one with whom the advisor might fight long and hard to ‘detox’ of their beliefs (and potentially end up losing the battle anyway). This is the core of investment management aikido – instead of fighting the client’s values, an advisor can redirect their energy in as beneficial of a way as possible!

Aikido is a Japanese martial art developed by Morihei Ueshiba. It has been described as a “synthesis of [Ueshiba’s] martial studies, philosophy, and religious beliefs.” As such, while aikido is a martial art, it is more than just a martial art and is intended to also provide insight into other areas of life.

Aikido is a Japanese martial art developed by Morihei Ueshiba. It has been described as a “synthesis of [Ueshiba’s] martial studies, philosophy, and religious beliefs.” As such, while aikido is a martial art, it is more than just a martial art and is intended to also provide insight into other areas of life.

In the book The Art of Aikido: Principles and Essential Techniques, Kisshomaru Ueshiba states:

The Founder Morihei was a genius who raised his art from a martial system of battle to a way of life, a spiritual path. He wanted his disciples not to fight but to work together, making a great joint effort to understand the true nature of Aiki [which roughly translates as ‘harmonized energy/spirit’]. This perfection of the human character is the first principle of Aikido. In Aikido, a mind set on victory by any means is not allowed, as it creates a very bad environment; rather one must learn how to work together with a partner, in a spirit of mutual protection, and to strive to demonstrate that harmony when performing the techniques.

According to aikido practitioner Eri Izawa, “the foundation of the self-defense aspect of aikido is the act of redirecting the attacker’s energy, rendering it harmless or even beneficial.” Likewise, when advisors receive pushback from clients that they feel could be harmful to the client if carried out, rather than arguing or persuading the client to change their mind, it may be helpful instead to think about how they could redirect that energy in a harmless (or even beneficial) direction.

While framing the financial planning process as a back-and-forth battle between opponents is perhaps not an ideal way to think about working with clients, viewing it through the lens of the principles of aikido can nonetheless provide insights for thinking about how to assist clients – particularly when there is a conflict of values between the advisor and client.

Values-Based Investing And Ideological Conflict

Because many clients have strong feelings around values that are relevant to their finances, many values-based investing strategies have become more widely available to appeal to investor values over the past decade. Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) practices often involve the use of particular funds that focus on companies with low risk ratings across various Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) criteria. Other values-based strategies may involve choosing funds that invest in companies that support an individual’s core values around areas such as sustainability, religion, and diversity.

One underappreciated aspect of values-based investing is the inevitability of an ideological conflict between an advisor and their client. This is because advisors will, at least in certain instances, be bound to have conflicting values from their clients, which can present a challenge for advisors trying to offer the ‘right’ advice to clients who may be reticent to take the advice on account of potentially conflicting personal values.

That ideological disagreements are inevitable is simply due to the fact that people are different. Even two individuals who broadly agree on some principle may still disagree on the specific points of the principle. For instance, two individuals who are passionate about protecting the environment may still disagree on whether nuclear energy is a harmful technology that ought to be avoided, or an environmentally-friendly technology that should be encouraged to reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Many advisors try hard not to impose their views on clients and stay neutral when it comes to client values related to political or religious affiliation. In some cases, advisors may agree to work within the constraints of the investor’s values, such as limiting the universe of potential investments to funds that avoid investing in fossil fuels. In other cases, however, advisors may conclude that they are not the right fit for a given client based on values-based needs (e.g., an advisor unfamiliar with Islamic tradition may not feel comfortable advising on Shariah-compliant funds). In these instances, advisors would generally just refer a prospect out to an advisor who may be a better fit rather than trying to change a prospective client’s religious values.

Interestingly, however, there is one area where advisors tend to be far more combative than others: dealing with fans of well-known financial pundits.

Fighting Pundit-Driven Client Values

While many financial advisors may disagree with the techniques espoused by popular financial media pundits, nonexperts often find them very compelling (as evidenced by the popularity of the pundits in the first place). Furthermore, in some cases, following the advice of a financial guru might have had a real positive impact on a client’s life – meaning that, for the advisor, convincing a client to simply ignore a popular pundit’s advice and start following the advisor’s (possibly conflicting) recommendations might be a difficult and even unrealistic proposition for the client.

For instance, the following comment was recently posted in an online community of financial advisors and garnered a fair amount of attention and support:

What is perhaps most interesting about the comment is the use of the term “detox”. It is essentially suggesting that, because Ramsey’s methods represent the ‘wrong’ approach to financial planning, advisors must overcome those ‘wrong’ views in the client’s mind, rather than looking for a way to channel such views in a more productive manner.

Notably, it’s hard to imagine an advisor wanting to “detox” a client of their religious, political, or other social ideologies – even when those beliefs could impact their finances. But once we enter the realm of financial ideology, it’s possible our own expertise – perceived or real – makes it harder for advisors to resist the urge to change their clients’ viewpoint.

Recall the core principles of aikido, which emphasize working in harmony with the opponent to redirect their energy in a beneficial way rather than trying to oppose or fight against it. Going back to the principles of Aikido, Eri Izawa has published a list of core principles/lessons of Aikido that include (with some excluded for brevity):

The foundation of the self-defense aspect of aikido is the act of redirecting the attacker’s energy, rendering it harmless or even beneficial.

For every attacking energy, there is a way to redirect it.

When presented with an attack, say “Thank you,” with a genuine smile as you neutralize the attack. This gives the aikidoka a real “boost” in effectiveness.

Put yourself in your opponent’s place, sometimes by physically moving closer to him so that you can better lead him.

If you use your muscles, the opponent will resist and it becomes a strength contest. You must lead with Ki (mental attention, mental direction, and energy).

Don’t think of the other as Someone Else. Think of both of you as “us.” It is easier to “lead us” than it is to “move you.”

If you become a very good aikidoka, you often simply “see” the right thing to do.

Notably, the list above contains many themes around understanding and accepting the intentions of one’s opponent, which, in the context of financial advice, corresponds with empathizing with clients first and foremost.

If an advisor is approaching a client engagement from the perspective of, “Dave Ramsey is an idiot and I need to detox my client of his dumb ideas”, there’s a notable lack of empathy and curiosity for why the client may have found Ramsey’s ideas so intriguing in the first place. Even if an advisor is ultimately going to suggest moving in a different direction on some topic, that doesn’t preclude that advisor from putting themselves in the client’s place to appreciate and genuinely try to understand what about the pundit’s advice resonated with the client.

And this is important because, ultimately, if an advisor can truly put themselves in the client’s shoes, it is likely the advisor will be better positioned to both help the client, and possibly even learn from them by gaining a greater appreciation for some element of a pundit’s philosophy (which may have been otherwise lost in the advisor’s knee-jerk reaction to reject those ideas).

This principle may be particularly useful for advisors to consider when deciding how to address clients who are fans of Dave Ramsey and other financial pundits. Instead of trying to change their clients’ beliefs, it may be possible to channel them in a more productive manner.

In order to use this strategy successfully, though, it is important for advisors to start from a place of genuine curiosity and interest in the client. If they approach a situation with absolute certainty that they are ‘right’, then it will be incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to learn or truly appreciate the client’s perspective.

Moreover, it is worth being very careful to appreciate the benefits an ideology may have for one person that don’t necessarily apply to all individuals. In other words, just because something works (or doesn’t work) for me doesn’t mean that the same will be true for someone else.

To relate back to the “Ramsey Detox”, imagine an advisor who is well-educated on the subjects of debt and behavioral finance, and may be completely comfortable with the idea of debt as a tool that (when used wisely) can lead to better financial outcomes.

Now imagine a client of that advisor who, after listening to Ramsey’s radio show, has decided to commit to living a debt-free life. In a meeting with the advisor, the client brings up Ramsey and the satisfying, debt-free life they have adopted, but the advisor interrupts and starts talking about why Ramsey is wrong to recommend living fully without debt.

In the case of this advisor, whose first reaction is to start fighting their client’s ideology to ‘detox’ them of their Ramsey-inspired views, they have already missed a key aspect of aikido by failing to try to genuinely understand their ‘opponent’ so that they can imagine themselves in that opponent’s place.

Simply because the advisor understands the potential benefits of debt doesn’t necessarily mean that all clients will benefit from leveraging debt. In particular, when an individual is susceptible to behavioral impulses that may lead to irresponsible spending, a no-debt constraint can have a lot of protective value for that individual (even if, when generalized to the whole population, it may not represent the ‘optimal’ strategy).

If advisors don’t take the time to appreciate and understand why a financial ideology may be beneficial to an individual, they may open the door to not helping (and possibly even doing harm) when they try to break down that ideology without understanding why it exists in the first place.

This is, in many ways, similar to appreciating “Chesterton’s Fence” – the principle, proposed by English writer and philosopher G. K. Chesterton, that no one should tear down a fence without first understanding why it was put there to begin with. More fully, Chesterton said the following:

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

If we don’t fully understand why a financial ideology/belief exists (and what value it may be providing), then we run a real risk of accidentally doing harm by trying to break down that ideology/belief. Of course, this is certainly not to say that we should never try to change a client’s mind (such as when following a certain path would likely be truly harmful), but simply that we need to take the time to better appreciate that ideology or belief before attempting to change it.

Moreover, even once we have identified why that ideology or belief may exist, it still may not be immediately clear that the proper course of action would be to try to destroy or defeat it. Rather, advisors can first consider whether that ideology or belief could be redirected in a manner that leads to an even better outcome for the client.

An Investment Portfolio Case Study: Building A Ramsey Portfolio

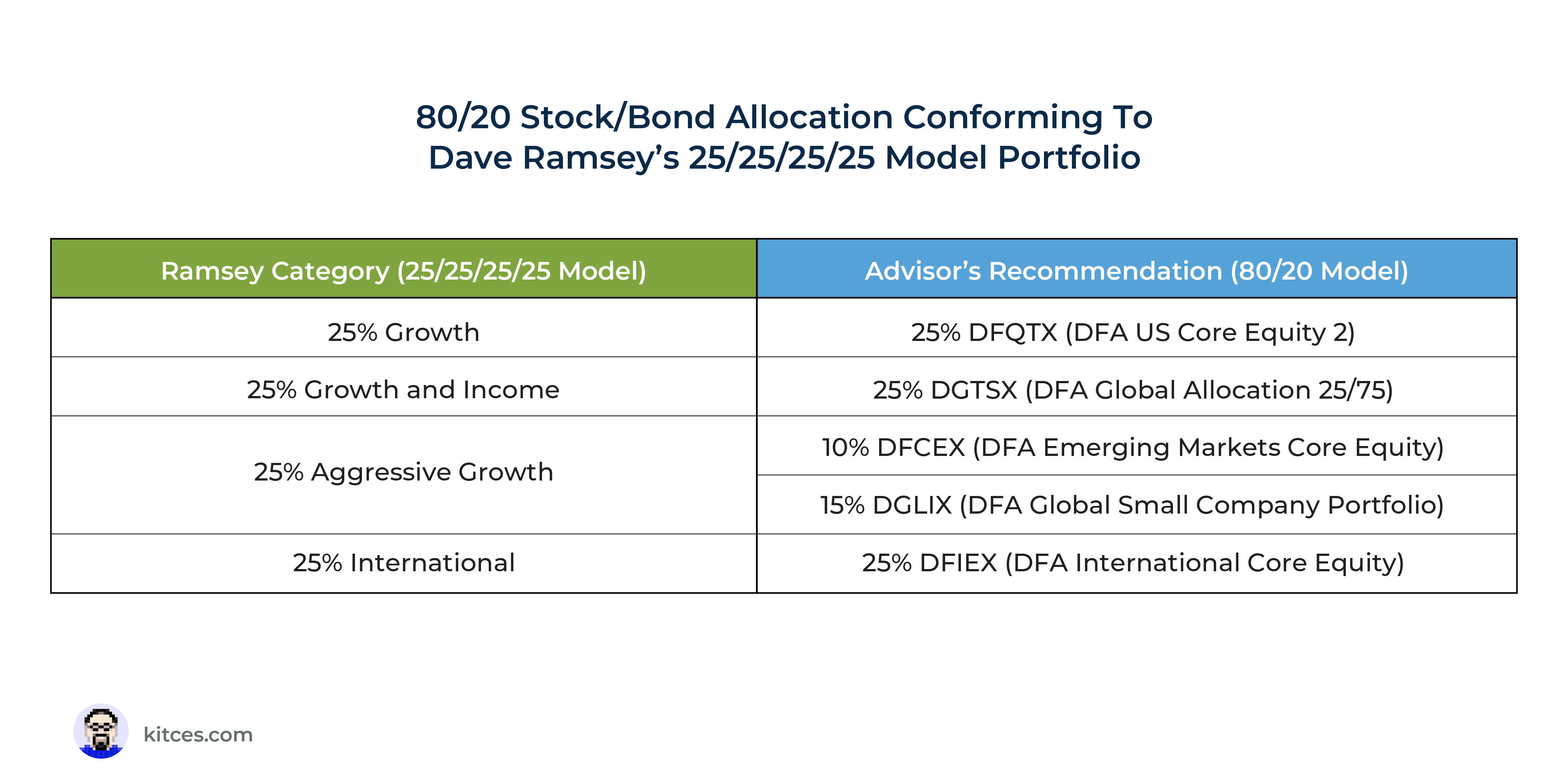

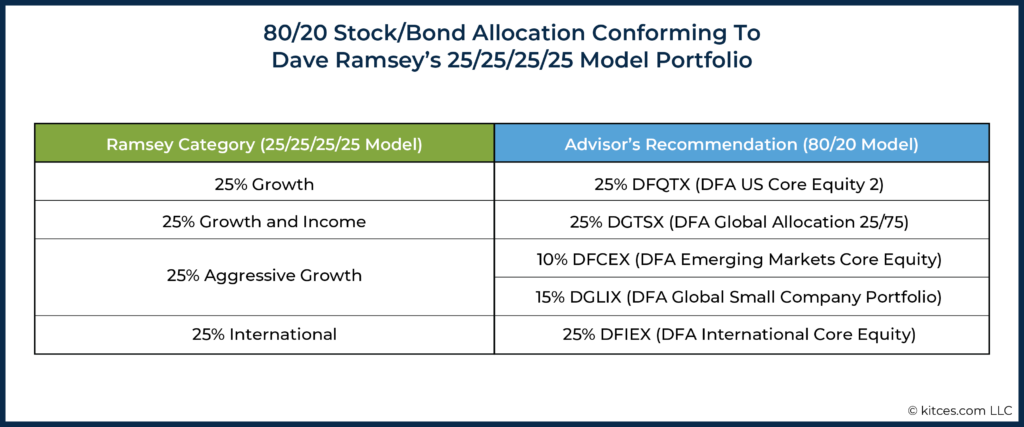

Another common belief that an advisor may wish to ‘detox’ from a Ramsey fan is Ramsey’s philosophy for building an investment portfolio, which generally consists of the following allocation:

- 25% Growth

- 25% Growth and Income

- 25% International

- 25% Aggressive Growth

The asset allocation categories above certainly diverge from the categories most familiar to advisors. They may seem a bit vague, since they are partially a relic from an older generation of actively managed mutual funds (and do not align very closely to the more descriptive Morningstar-style categories that have gained popularity in recent years), but Ramsey does provide further insight into what he has in mind with respect to each category.

Generally speaking, you could think of Ramsey’s “Growth” allocation as broad US stocks, “Growth and Income” as balanced funds that include both stocks and bonds (there’s a common misconception that Ramsey is not a fan of bonds, but his opposition appears to more so be standalone bond funds), “International” as developed international stocks, and “Aggressive Growth” as inclusive of categories like small-cap and emerging markets stocks.

Now suppose an advisor who takes an academic approach to investing, following evidence-based principles such as factor investing, is approached by a Ramsey fan who is interested in building a portfolio that follows the 25% allocation to each of the categories above. More likely than not, the advisor’s immediate reaction to the proposal is that they hate it.

But rather than immediately arguing that the prospective client is wrong in wanting to follow Ramsey’s advice, let’s take a step back and try to appreciate why someone might like a portfolio like the one above.

For advisors with access to sophisticated modeling and rebalancing software, one aspect of such a portfolio that can be easy to overlook is the value of simple 25% allocations to four different categories. For someone building a portfolio on their own, the risk of making a mistake with their asset allocation has dropped dramatically by applying consistent 25% weightings across each category. Contrast a 25/25/25/25 allocation with say, a 36/18/8/40 allocation, and it is easy to see how the potential number of errors may be dramatically higher with the unequally-weighted portfolio.

Moreover, even for someone working with an advisor, insisting on a simple 25/25/25/25-type portfolio can make it much easier for the client to understand the ongoing process of managing and rebalancing the portfolio. If a portfolio is made up of 15 different ETFs – some of which have names that might mean absolutely nothing to the non-initiated – it would be much harder for a client to understand when (and why) their advisor would recommend rebalancing their portfolio than when there is a basic 25% target to each category.

Another aspect to appreciate about a 25/25/25/25 allocation like Ramsey’s is that the categories aren’t overly rigid to the point that an investor would struggle to apply them in practice. Of course, that can be both a strength and a weakness, but there’s definitely some potential value in being able to apply the same broad framework whether one is investing in, say, a Roth IRA or a 401(k) plan with more limited fund selection.

For instance, perhaps an individual using Ramsey’s investing approach has a 401(k) plan that doesn’t have a standalone emerging markets fund, but does have a small-cap fund. Because the Aggressive Growth category is relatively flexible and can include both small-cap and emerging markets, that allocation could be fully comprised of small-cap funds and remain in line with the overall strategy.

There’s likely far more to appreciate from a simple allocation like the one above, but it is much easier to gain that appreciation by trying to understand why such a portfolio could be useful before fixating on the reasons it isn’t.

Next, we can also think about the non-monetary value that a client may receive from holding a portfolio that aligns with the allocation above. Again, let’s suppose we are talking about a client who is a devoted Ramsey fan. In this case, the reality – perhaps unfortunate, if one wishes to view it that way – is that an avid Ramsey listener is probably going to engage with Ramsey far more than they will with their advisor.

Ramsey puts out so much content that most people would struggle to even keep up with all of it over the course of a week. By contrast, an advisor who holds meetings with clients only once or twice a year has far fewer opportunities to get their message across. Ramsey fans also tend to find the content highly entertaining and authentic in a way that many advisors struggle to emulate in their own messaging. So, for better or worse, Ramsey fans who trust Dave are going to place a lot of weight on his teachings.

If advisors give advice that aligns with Ramsey’s teachings, it can be reasonable to presume that their Ramsey-fan clients will be less skeptical of such advice and more excited about putting what they’ve learned about into practice. By contrast, if there’s a constant tension between what advisors are telling them and what they’ve learned to do elsewhere, that’s likely going to reduce enthusiasm and present a cause for concern (as well as a substantial level of confusion).

So how should an advisor respond?

Using Investment Management Aikido To Advise Clients With Conflicting Beliefs

When an advisor is faced with a client with different beliefs or values from their own, and who is resistant to their advice, one option is to fight that client’s beliefs and try to explain why the client (and Ramsey himself, for clients who are fans) are wrong, and why instead they should invest according to the advisor’s preferred approach. In other words, the advisor might want to ‘detox’ the client of their beliefs (which, as noted in the Internet post above, can be a long and ultimately losing struggle).

Alternatively, an advisor could embrace the principles of aikido, and, instead of trying to ‘defeat’ the client through sheer force of will by telling them they are wrong, try to redirect the client’s energy in a more productive manner.

Perhaps, rather than approaching the situation from the perspective of trying to tear down the client’s beliefs, the advisor might instead choose to build a portfolio that honors those beliefs while still being a high-quality portfolio that the advisor has conviction in. Because ultimately, while many advisors might focus on the differences between Ramsey’s investing philosophy and their own, there still could be enough overlapping concepts between the two (such as diversification and keeping a long-term perspective) to allow for broad agreement between them.

From this perspective, building the portfolio becomes an exercise that is essentially the same as any other SRI/ESG/other values-based investment philosophy. In order to best align with the client’s values, the advisor may need to operate from a slightly limited fund universe, which (despite not being 100% optimized from the advisor’s perspective) can still be completely worthwhile as a means to building a portfolio that aligns with a client’s bigger-picture values.

Returning to the example above, imagine that our hypothetical advisor in this scenario has listened to and understands the client’s reasons for following the Dave Ramsey portfolio approach. Rather than attempting to ‘fight’ the client and try to talk them out of their belief, the advisor instead chooses to implement investment management aikido by adapting their own recommendation of an 80/20 stock/bond allocation to Ramsey’s strategy, knowing that the client has already bought into it.

Let’s presume that the advisor, who likes to factor-tilt portfolios and appreciates an academic approach to investing, chooses to use DFA funds; this gives them plenty of options to build a portfolio allocating 25% to each of the asset classes that Ramsey is a fan of.

Here’s an example of how a hypothetical portfolio could conform to Ramsey’s 25/25/25/25 model:

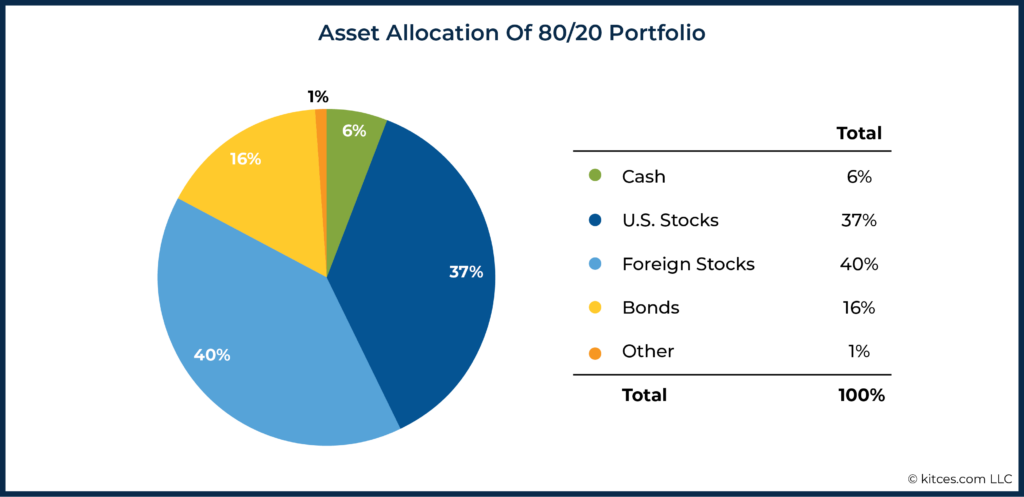

The resulting portfolio has a roughly 80/20 stock/bond allocation with reasonable global diversification while still otherwise meeting all of Ramsey’s 25/25/25/25 criteria.

While the portfolio diverges from Ramsey’s approach in some minor ways (such as by including 2 funds in the “Aggressive Growth” category instead of just 1), these could be acceptable changes for the client because the advisor can still summarize the 25/25/25/25 allocation, which helps the client understand the portfolio at the rolled-up level consistent with the Ramsey model.

Now suppose that the advisor had instead fought hard to persuade the client to invest in their ‘standard’ 80/20 stock/bond portfolio model. Even if that represented the ‘ideal’ portfolio from the advisor’s subjective perspective, the portfolios still would have ended up being very similar – with the exception that the 25/25/25/25 portfolio would be far more psychologically appealing to the client. Which means that pushing for the 80/20 model would simply make the client feel less inclined to trust the advisor’s advice, even if the underlying 80/20 investments still fit the 25/25/25/25 portfolio!

Just as an environmentally conscious investor might be more excited about saving and building wealth by using sustainable funds, a Ramsey fan may be more excited to save and invest when their methods for doing so map onto their Ramsey-influenced understanding of the world. For financial advisors, understanding – and appreciating! – the client’s values can make all the difference between working with an engaged and enthusiastic client, and one with whom the advisor might fight long and hard to ‘detox’ their beliefs (and end out losing the battle anyway).

This is the core of investment management aikido – instead of fighting the client’s values, an advisor can redirect their energy in as beneficial of a way as possible, while also appreciating that there may be wisdom to any particular approach that we as individuals can easily overlook.