There has been a lot of recession talk in recent months so it shouldn’t have come as a surprise when my wife asked me to explain to her what a recession actually is a few weeks ago.

To which I replied:

It’s harder than it sounds at first blush.

Some people assume a recession is when real GDP contracts for two consecutive quarters.

Simple enough, right?

But this definition hasn’t been fulfilled in two out of the last three recessions.

The 2020 downturn lasted just two months, not two quarters. And in the brief 2001 recession real GDP didn’t contract for two quarters in a row either.

That’s because recessions are officially determined by a group of economists at the National Bureau of Economics (NBER) and they use a host of measures beyond real GDP to make it official.

Here’s how they describe their Business Cycle Dating criteria:

The NBER’s definition emphasizes that a recession involves a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months. In our interpretation of this definition, we treat the three criteria—depth, diffusion, and duration—as somewhat interchangeable.

The determination of the months of peaks and troughs is based on a range of monthly measures of aggregate real economic activity published by the federal statistical agencies. These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions. In recent decades, the two measures we have put the most weight on are real personal income less transfers and nonfarm payroll employment.

That’s a mouthful but we can basically boil it down to income and employment. If income and employment turn south, there’s a good chance economic output will be lower.

The strange thing about the current setup is output is slowing but income and the labor market are still solid.

Jon Hilsenrath wrote about this divergence in a recent piece for the Wall Street Journal:

Robert Gordon, a Northwestern University economics professor and member of the NBER’s business cycle dating committee, said this might be a situation in which other indicators point to recession but the job market doesn’t, or it lags behind atypically for several months.

“We are going to have a very unusual conflict between the employment numbers and the output numbers for a while,” he said.

Matthew Klein says personal income is as high as it’s ever been:

The typical U.S. household earned more than ever as of May—even after accounting for inflation. And their finances were secure, with consumer spending rising at a steady clip even as their saving rate remained elevated.

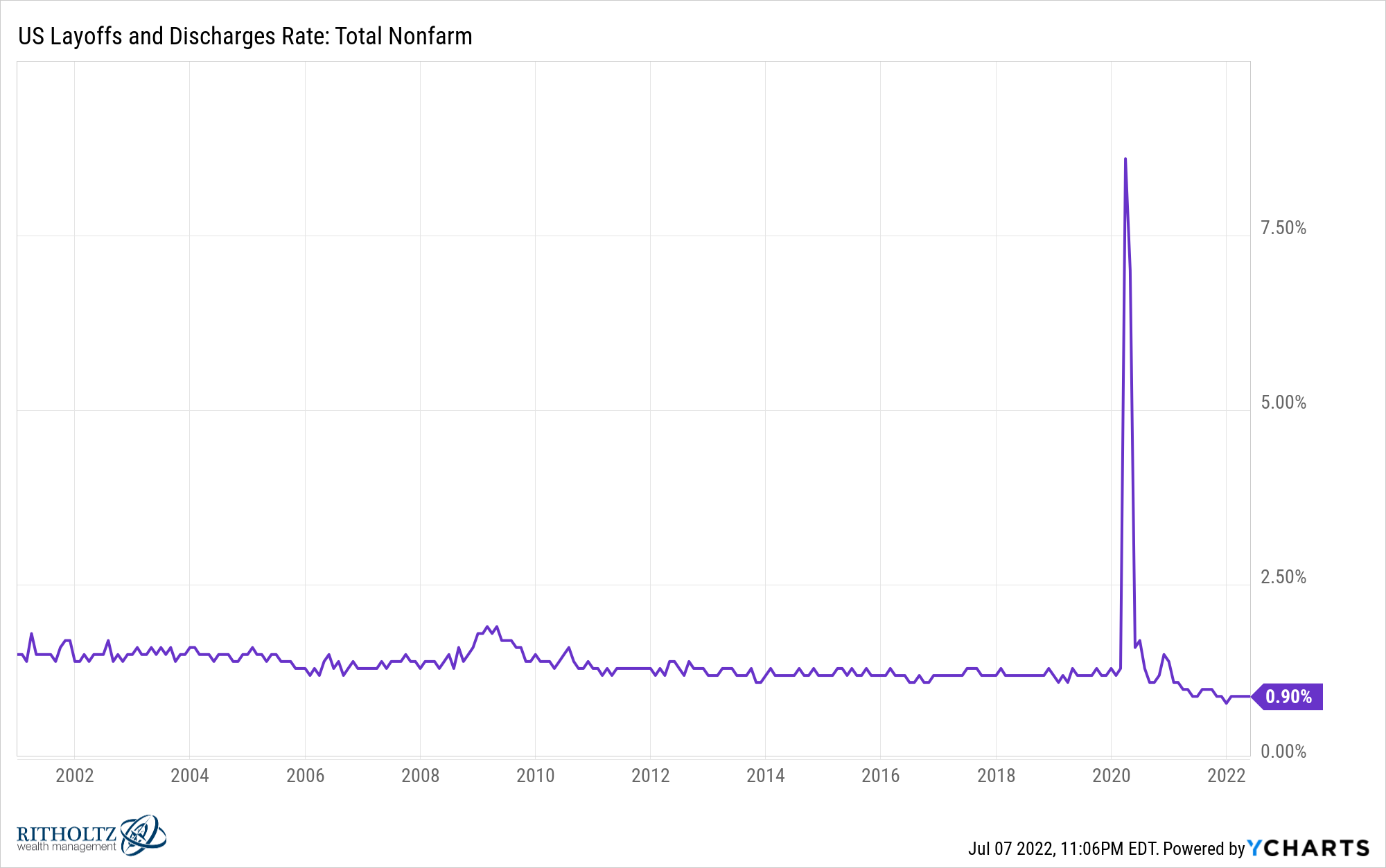

Before the pandemic, the lowest layoff rate ever was 1.1%. It’s now been lower than that for more than a year:

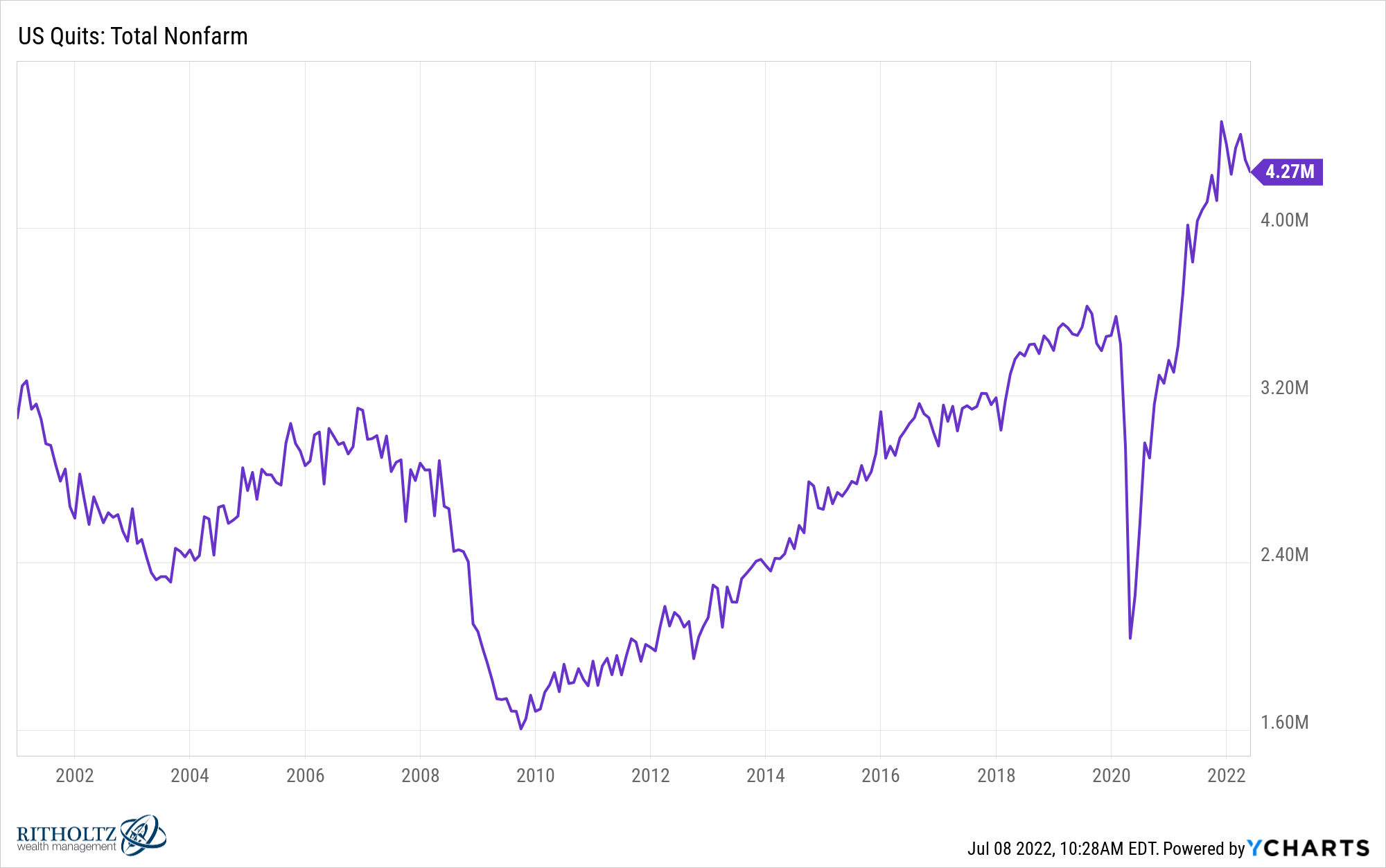

And this is happening at a time when the quits rate is higher than at any point pre-pandemic:

So people aren’t afraid to quit their job and they’re not getting laid off. This is a sign of a healthy labor market.

The unemployment rate also remains low at just 3.6%.

The U.S. economy added 1.6 million jobs in the first quarter of this year. Another 1.1 million jobs were added in the second quarter.

Those numbers don’t look recessionary to me.

Now, it’s possible personal income and unemployment data will soften in the coming months from some combination of the Fed raising interest rates and inflation remaining stubbornly high.

But it’s also increasingly likely we could see real GDP contract while these measures remain strong.

And if that happens, certain people are going to lose their minds.

Some people want to be right about a recession prediction. Some people in finance are pessimistic by nature. Some people think the system is rigged. Some people just want to watch the world burn.

Here’s the thing — it doesn’t really matter to most regular people if real GDP falls two quarters in a row but NBER doesn’t label it an official recession.

Policy wonks, macro tourists and markets people like me who find this stuff interesting will care but the only thing that matters to normal people is their own personal economy.

There’s the old saying that a recession is when your neighbors lose their job while a depression is when you lose your job.

If you get laid off in the coming months it doesn’t matter what some council of economists says about the economy. You’re going to feel it, emotionally and financially. Losing your job is a personal recession no matter when it takes place in the economic cycle.

And even if we do go into the official definition of a recession, if you’re able to hold onto your job, keep saving money and avoid working in a segment of the economy that gets hammered, it won’t really feel like a recession to you personally.

Unemployment rates, inflation rates, personal income averages, savings rates and all kinds of other economic data can do a decent job of helping understand trends in the economy on the aggregate.

Yet no individual or household is representative of those averages. We all have our own unique preferences, spending habits, finances and circumstances.

It may seem like splitting hairs to argue about the definition of a recession but I just want to prepare you for a potentially bizarre economic scenario in the months ahead where some people will argue we’re in a recession while others will refute that idea vigorously.

Things are going to get weird.

Michael and I discussed the weird economic times we find ourselves in and more on this week’s Animal Spirits video:

Subscribe to The Compound so you never miss an episode.

Further Reading:

Why Everyone Thinks the Inflation Numbers Are Wrong

Now here’s what I’ve been reading lately: