As a species, human beings love to compete with one another. I see this competitive nature on display every day with my six-year-old James and nine-year-old Max. Who can get up the stairs first? Who can finish their dinner first? Who gets to cuddle with daddy first? (Okay, full disclosure here, it’s usually a battle over who can cuddle with mommy!) Winning, doing better than someone else, and outperforming are in our blood. In many ways, this concept also applies to analyzing your portfolio’s investment performance. But to accurately determine outperformance, it’s important to compare your results against the proper standard or benchmark.

What Is Winning?

The other day after Max’s baseball game, James (full of liquid courage from drinking his blue slushy) challenged me to a race around the bases. Not being from the “participation trophy era” of today, I went full out and handily beat him. Now, my friends often joke that my legs are so skinny that people might chalk them up if I passed a pool hall. Nonetheless, it was not a “fair” race, as my legs are much longer and my body is more developed than my son’s. (I be old!) Of course, if James were to run against kids who were closer to his age, it would provide a much better litmus test of how fast he really is.

The same idea holds true for comparing the performance of your portfolio. Often, advisors request that I take a second look at a portfolio when clients ask about their returns compared with “the market.” For most investors, the market refers to the S&P 500. For the most part, this index is composed of large-cap U.S. equity. So, unless you own a similarly constructed portfolio, it is not a fair comparison.

Instead, a more appropriate benchmark is a blended index that includes the Russell 3000 (domestic equity), the MSCI World ex-U.S. (international equity), and the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond (bonds) indices, as well as cash. In addition, the percentage in each index should mirror a client’s actual allocation to domestic equities, international equities, bonds, and cash. To “win,” clients should evaluate whether their investments beat this blended benchmark.

Everybody Want to Rule the World

The above references a song from 1985 by Tears for Fears. It falls outside my top 1,000 favorite songs; however, it does speak to how the average investor wants to make as much as the market, as long as the market is up. It is also perfectly normal to have a short-term memory and forget that the S&P 500 was down 37 percent in 2008. Advisors work with clients to determine their risk tolerance and, in turn, the asset allocation that aligns with it. The more risk that you are willing to take on, the better the probability that your return will be higher because of it. Conversely, with higher risk comes a higher chance of more loss of principal when the market falls.

What Goes Around, Comes Around

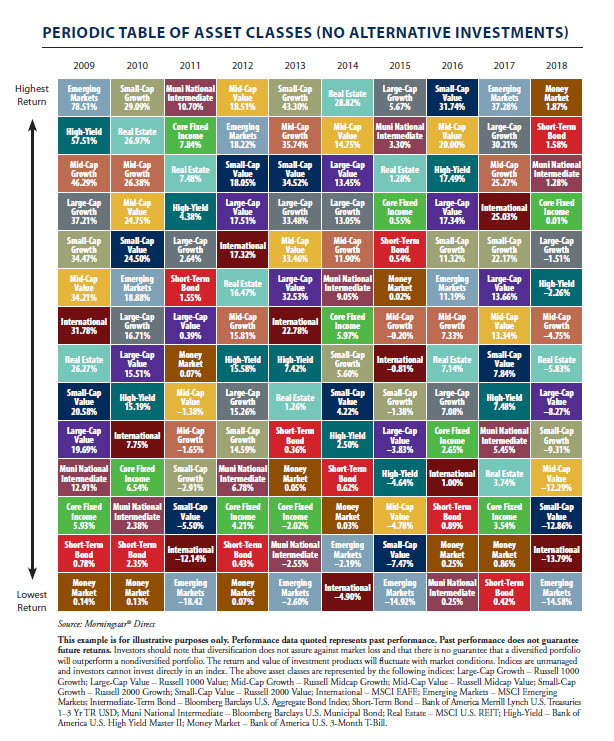

This brings us to the concept of diversification. With hindsight, it is not unusual for an investor to think, “why didn’t my advisor just put all my money into Amazon and Apple?!” Cue the reference to the dot-com bubble of 2000 that I witnessed firsthand as a stock trader. Now, I am not saying that today’s tech giants are analogous to those that crashed like Pets.com. But Newton’s law of gravity of what goes up must come down applies here. How much they go down is another story. The point is something that has been constantly emphasized with all investors: diversification is essential to long-term performance. Like the circle of life (the new Lion King now playing in a theater near you!), an asset class can do great one year and terrible the next. For instance, emerging markets equity was up 37.28 percent in 2017 and down 14.58 percent in 2018. The Callan chart below illustrates this concept best.

A Marathon . . . Not a Sprint

Back in 2000, I decided to run the Boston Marathon even though I had never run more than 5 miles at a time in my life. Shaped more like a rhombus than a runner, I realized that the only way that I could run 26.2 miles would be to run relatively slow and gradually build up my endurance. In the short run (pun intended!), my tortoise-like pace kept me in the back of the pack. In the long run? I was able to endure and finish the race, while others that were once ahead of me fell by the wayside. I had accomplished my goal.

Investing can be looked at in the same light. It is about accomplishing your goal, whether that’s owning a home, putting your kids through college, or retiring at a certain age. You can only sprint for so long. The old adage of slow and steady wins the race applies here.

The Bottom Line

I teach my boys that it is okay to be competitive but that it is also okay to lose. Both, in the long run, will make them stronger and help them achieve their goals in life. They should measure their relative success or failure against appropriate benchmarks. Investors would do well to do the same.

Editor’s Note: The original version of this article appeared on the Independent Market Observer.