Executive Summary

Amid estimates that nearly 40% of all financial advisors are likely to retire in the next 10 years, the need for a new generation of advisor talent is clear. To meet this challenge, CFP Board’s Center For Financial Planning has engaged in fundraising for several years to fuel campaigns that have focused on building the advisor workforce of the future. But a recently announced increase in annual CFP certification fees – shifting the Center’s efforts from voluntary fundraising amongst donors to a mandatory cost for all CFP certificants, as 35% of the fee increase is allocated to Workforce Development efforts – raises an important question: Who actually benefits the most from increasing the number of students pursuing degrees in financial planning?

Insurance companies and broker-dealers in the business of manufacturing products and hiring advisors to sell them often dominate career fairs and job boards, frequently drawing in graduates of CFP Board-approved education programs. But these positions are often tenuous for new advisors, with extremely high failure rates, driven in large part by compensation that is reliant primarily on commissions from product sales. In fact, for decades, approximately 80% of those who take such ‘financial advisor’ sales jobs with product manufacturers leave those companies (and potentially the industry) after 3–5 years! And while CFP Board does emphasize in its Career Guide that commission-based income is lower initially for more upside in the long run, the guide does not acknowledge the drastically higher failure rates that come with commission-based roles.

The added complication is that, while this structure of hiring a large number of new advisor recruits with a high level of churn results in a high volume of aspiring planners potentially leaving the industry altogether, it is quite profitable for the insurance companies and broker-dealers themselves. As from the perspective of the product manufacturer, spending money on recruiting to get new advisors who bring their ‘natural-market’ list of 100 friends and family means that the company ‘gets’ 100 leads at the cost of nothing more than some licensing exams and a recruiter to bring them in – as new advisors who are recruited but don’t sell much of anything don’t get paid much of anything… but the insurance company still gets to keep the list of 100 prospects (and in many cases, the trails from the new advisor’s early sales that no longer have to be paid after the advisor leaves). Which, at scale, can actually be even more cost-effective as a lead generation strategy than simply buying leads from a third-party lead generation service (and thus why such high-turnover recruiting strategies have persisted for decades)! Because of this ‘cost-effective’ source of leads via high-turnover recruiting, a number of the industry’s product manufacturers have historically been corporate sponsors of the CFP Board-affiliated Center for Financial Planning’s Workforce Development initiatives in order to build the pool of potential recruits (for those companies to potentially hire as their lead-generation source!).

But now, with its recent increase in CFP certification fees, the Center’s funding appears to be shifting: out of CFP Board’s recent $100 increase to its annual certification fee, $35 is allotted to the Workforce Development program, which means now the Workforce Development initiatives that historically were funded voluntarily by product companies in alignment with their sales efforts will instead be funded on a mandatory basis by all CFP certificants… effectively turning a portion of the CFP Board’s certification fee into a marketing expense for product manufacturers via their high-turnover recruiting efforts (which will simultaneously undermine the CFP Board’s own growth goals as a result of that high turnover).

Given the substantial risk that CFP Board’s increase in certification fees is funding the marketing efforts of product manufacturers, there are steps that CFP Board can take to ensure that fee increases are actually supporting the long-term expansion in the number of financial planners. First and foremost, CFP Board needs to determine and demonstrate that young people who enter CFP Board-registered programs actually do end out becoming CFP certificants in meaningful numbers, and are not just a conduit to high-turnover sales jobs. This could be done through a study working with the largest CFP Board-registered programs to determine whether their students took an industry job after graduating, how many are still in the industry 3 years later, and how many of them ultimately got their CFP marks, among other questions. With this data, CFP Board could then update its Career Guide to reflect the realities of what career choices and starting firm paths really lead to increases in success (or failure) as a new financial advisor.

Ultimately, the key point is that if the CFP Board is going to turn the Center for Financial Planning from a voluntary contributed-income program into one funded by a mandatory portion of CFP certification fees – especially since nearly 50% of all CFP certification fees are no longer for the operation of the CFP Board itself, but for the organization’s own growth initiatives – it needs to do the research and bring the data to show that its initiatives will be a good allocation of capital. And until it can determine whether increasing the flow of students will result in a larger advisor workforce or just a higher volume of advisor churn (and also update its Career Guide to help students navigate those risks), CFP Board should delay the increase of at least the Workforce Development portion of its new certification fee.

Why High Advisor Turnover Is Actually Profitable For Insurance And Investment Companies

As the saying goes in the financial services industry, “Financial products are sold, not bought”.

What this means is that when an insurance or investment company manufactures a product – from a life insurance policy to a mutual fund – consumers rarely just raise their hand of their own volition to buy the product. It’s a crowded marketplace, consumers have an overwhelming number of products to choose from, and many or even most would rather spend their money on something more immediately gratifying. As a result, it requires someone to find potential customers and convince them to buy most insurance and investment products. The financial product usually has to be sold.

From the perspective of an insurance or investment product manufacturer, this necessitates an expense – typically in the form of an upfront and/or trailing commission – that is paid to the agent or representative selling the product. Simply put, if you manufacture a product, it costs money to get it distributed to customers. It’s a cost of doing business, and the cost is built into the price of the product itself.

The Cost Of Distributing Financial Products Through Advisors

The fact that distribution is a cost that raises the price of (and can lower the competitiveness of) the product gives manufacturers an incentive to find the most cost-effective ways to distribute their products.

As a result, some companies simply manufacture good products, pay competitive commissions, and try to make the product competitive enough that salespeople will want to sell its features and benefits. Others have tried to strip the commissions out of their products, and instead pay new RIA wholesalers to call on fee-only channels to use their products without the commission cost. Still other companies have adopted direct-to-consumer models, hoping that the cost of doing direct-to-consumer marketing – e.g., various forms of media advertising – in lieu of traditional commission-based distribution, will be more cost-effective. And some companies look to other intermediaries (like websites) and allocate their distribution costs there (which is why insurance isn’t necessarily cheaper on ‘buy-insurance.com’ type websites – they’re simply participating in the same distribution economics and collecting what would have gone to a salesperson’s commission because the cost is already built into the product).

And the cost of distribution matters, because the cost to get a client is expensive. In the last Kitces Research on Advisor Marketing, advisors averaged more than $3,000 in acquisition costs just to get a single client. Even ‘just’ getting cold leads of people who have expressed some kind of interest in learning more about some financial services product are often $75–$150+ per lead (and when only 1-in-20 or even fewer may close; the net cost is similar to other client acquisition costs).

In fact, the demand to get new clients is so high that lead-generation services are one of the fastest-growing AdvisorTech categories because at least some RIAs have shown a willingness to pay as much as 25% of lifetime revenue to get a single client via a high-quality introduction (which, for a $1M client, could amount to $2,500 per year, for literally a few decades). Which means that, when it comes to lead generation, there are few opportunities for ‘free’ (or even cheap) lunches.

Why Financial Services Firms Ask For ‘100 Friends And Family’ Natural Market Lists

For financial advisors starting their careers, the high cost and competitive challenges of getting new clients have translated into an extremely high failure rate – where, historically, it’s not uncommon for 60%+ of new hires to be gone in a year, and many insurance companies and wirehouses have struggled to lose anything less than 80% (!) of their new recruits over the first 3–5 years. (In other words, only 1-in-5 who joined a firm were typically still around at that company 5 years later!) As again, the competition to get new clients is brutal, and most people who try – especially with limited sales experience and limited capital to spend on marketing – just don’t succeed.

Which is why product manufacturers that hire financial advisors often seek out or encourage new advisors who have some kind of ‘natural market’ – an existing network of family and friends, or perhaps colleagues from a former career – to whom the new advisor can reach out and have better odds of getting successful sales than ‘just’ cold calling.

Still, though, one of the astonishing aspects of the financial services industry is that, even though this has been the model for decades upon decades, it still has a very high failure rate, where 80%+ gone-after-5-years remains common. Except, as it turns out, that’s because it’s actually profitable for product manufacturers to have high advisor attrition, especially for those who bring a natural market list of 100 friends and family to try to sell to.

From the insurance company’s perspective, often the primary benefit of hiring new advisors is their natural market list of friends and family. After all, if the insurance company ‘just’ wanted to hire people who knew how to sell, they could solicit them away from competing companies (e.g., by enticing them with better payouts or bonuses for the most productive salespeople). However, hiring a new advisor who brings their list of 100 friends and family brings an actual list of prospects. The same kind of list that other advisors are paying third-party lead generation companies to provide!

For instance, imagine for a moment that an insurance company has to pay $100,000/year (just to make the math round and easy) to a sales manager whose job is to recruit and train new advisors. Over the span of a year, the sales manager brings in 2 new recruits every month, or 24 throughout the year. And each new recruit, when they come on board, is required to bring their list of 100 friends and family.

That means, by the end of the year, the sales manager has brought in 2,400 new names of people that can be called upon. Otherwise known as 2,400 leads. In a world where leads can cost $100 each, that makes the ‘market value’ of those leads a whopping $240,000!

Except the insurance company got them for ‘free’ – as the new advisors aren’t paid until they actually sell anything – resulting in a lead cost of ‘only’ the cost of $100,000 of sales manager salary, and perhaps a few thousand dollars in initial licensing expenses to help all the new advisors pass their Series 6, 63, and Life & Health sales licensing exams. Which amounts to just $100,000 lead-generation costs ÷ 2,400 leads = $42/lead, or less than half the traditional cost for advisors to buy warm leads. The key point is that recruiting new advisors with friends-and-family lists is a cost-effective lead-generation strategy.

Of course, if/when those new advisor agents actually sell the company’s products to the names on their list, they will earn additional compensation in the form of commissions. But commissions are already built into product expenses. And product companies further mitigate this cost in the early years with a grid structure to its commission payout rates based on ‘production’.

In other words, advisors only get paid a percentage of the sales production that they generate, and those with lower sales numbers – most commonly, newer advisors who haven’t even had the opportunity to ramp up to a substantial volume yet – get paid a lower percentage of their commissions.

From the product manufacturer’s perspective, this helps to equalize their distribution costs across their entire sales force by having higher payouts for experienced advisors, and lower payouts coupled with additional recruiting and sales training expenses that add up to a similar total distribution cost for newer hires.

How Product Companies Profit From High Advisor Turnover

New recruits are profitable to product manufacturers because the company only pays for actual sales, can pay a lower commission percentage to help cover their training costs, and makes a ‘return on investment’ on their recruiting efforts because the new recruits bring their own marketing lists. Which, in the aggregate, across dozens and hundreds and thousands of new recruits, is the equivalent of hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars of ‘free’ lead generation.

This is also why, historically, product companies didn’t pay upfront salaries, and the initial income they did pay (if anything) was typically only a ‘draw’ against future commissions. Because paying an ongoing salary for a new advisor who brings a one-time marketing list of their existing friends and family won’t be profitable. The model only works when the costs are contingent on sales the advisor makes (commissions, and the draw against those commissions), or involve only the recruiting overhead (sales managers and other recruiting expenses) it takes to get the list of leads in the first place and then cutting costs once the leads have been obtained.

Because in such structures, it also means that when a new advisor ‘fails’, the insurance company has very little cost (if there were no sales made, there would be no commissions paid), but the insurance company still gets to keep the list of leads. As the whole point of this kind of recruiting approach is not simply to find new advisors; it’s also to get all the ‘free’ leads from the ones who fail. And the more advisors who fail – and the more quickly those advisors fail – the lower the cost of the natural market list of leads the product manufacturer gets to keep.

In addition, it’s important to remember that insurance and investment product commissions are typically not all upfront. Instead, there’s usually an upfront component, but also an ongoing trail in each year thereafter that the customer continues to maintain/renew. But if the advisor fails, the insurance company often no longer has to pay out that trail. The customer can become a ‘house account’, serviced directly by a centralized (at that point, salaried) home office staff member who handles a high volume of low-maintenance customer accounts/products. Which, in the aggregate at scale, is even less expensive than paying trails (and again, more profitable for the product manufacturer to have the original advisor recruit gone).

In other words, for new advisors who either can’t get any sales or only get ‘a few’ sales, it’s actually more profitable for the product manufacturer to see them terminated. Because the company still gets to keep the list of prospects and keeps all the future trails, all while it has little to no upfront obligation because it didn’t pay much of anything in the way of a salary.

Nerd Note:

In recent years, actual starting salaries have begun to emerge at many insurance companies and wirehouses, and the product manufacturer takes a greater ‘risk’ on its new advisors. However, this shift has largely been tied to the rise of product companies expanding their product bench – from insurance companies adding subsidiary broker-dealers to offer investments, to wirehouses increasingly offering banking and lending products – which means it’s more profitable in the long run to get that new advisor’s prospective client because of the new cross-selling potential.

In other words, an insurance client from a new advisor’s natural market list today may need more insurance later, and then mutual funds as they begin retirement savings and have their first job change and rollover, and then a 529 plan for the kids when they get married and start a family, etc. The end result is, simply put, that when companies have more products to sell, a lead is more valuable in the long run, which has made product manufacturers willing to ‘risk’ a little more on new advisors (in the form of a more attractive starting salary for a year or two), but only because their natural market lead list is more valuable now.

And salaries still often ‘wean’ after the first 1–2 years, because, in the long run, the product company doesn’t have an incentive to continue to pay beyond the point that it has already harvested the optimal value from the new advisor’s list of leads. (At that point, either the new advisor can independently generate new leads to generate ongoing ‘value’ in selling the company’s products, or the company ends the relationship.)

In fact, in this context, product manufacturers actually benefit from a higher attrition rate amongst their new advisors, where only the most effective ongoing prospectors who can continue bringing in new clients are able to stay. For the rest, once they have fully executed on their original 100-person list in the first ~3 years – where the product company still benefits from both the profitable product sales to those prospects, and improved profits because they won’t have to pay future trails – the company’s desire to retain that new advisor taps out when the sales opportunities are exhausted.

Thus why, in the end, the financial services industry recruits an astonishing number of ‘new recruits’ every year, with many of the leading insurance companies and wirehouses each hiring literally thousands of new recruits – who are each expected to bring their lists of 100 friends and family – year after year. Because from a marketing perspective for the product manufacturer, high turnover to get to the next new recruit and their prospect list is often more profitable than continuing to develop the struggling advisors who are already there.

How CFP Board’s Fee Increase For Workforce Development May Fund High-Attrition Sales To Its Own Detriment

Over the past 20 years, it has become less and less appealing to be a salesperson. In part, this appears to be driven by demographic trends, as Gen X and especially Millennials have not shown the same interest in sales positions as prior generations. And in part, it’s because the ‘sales’ side of the business has gotten harder, from consumers that are more resistant to sales pitches amidst the constant bombardment of advertising, to the rise of Do-Not-Call lists that undercut what was historically one of the primary alternatives to natural market lists (i.e., cold calling).

The end result of this dynamic is that the advisor workforce has been aging quite significantly, with Cerulli estimating that the average advisor today is in their early 50s, and that nearly 40% of all advisors are likely to retire in the next 10 years. Relative to a base of nearly 300,000 financial advisors, that means the industry needs to recruit more than 100,000 advisors in the next decade just to break even. And that’s especially challenging if a large volume of the financial advisor jobs being hired have 80%+ turnover in the first 3–5 years, as it means we may need to recruit half a million new advisors in the traditional model just to find 100,000 who remain by the 2030s!

CFP Board’s Center Begins Corporate Fundraising For Workforce Development

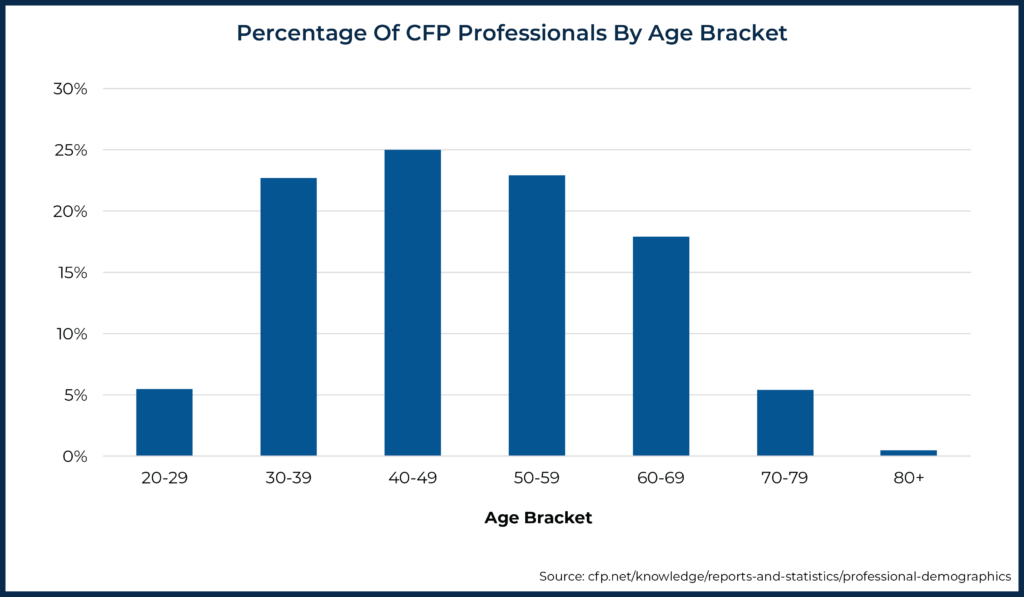

Over the past several years, CFP Board has become increasingly involved in the issue of advisor workforce development as well. As CFP professional demographics are similar to the overall advisor demographics – with an average age of just under 50 – there are still (slightly) more CFP practitioners over age 70 than under age 30.

And when, in the end, CFP Board’s mission is “to benefit the public by granting the CFP certification and upholding it as the recognized standard of excellence for competent and ethical personal financial planning”, which implicitly means granting the CFP marks to more advisors over time, seeing an ongoing influx of new advisors who can become CFP certificants (i.e., workforce development) is in the interests of CFP Board as well.

Which led several years ago to the launch of CFP Board’s “Center for Financial Planning” with an initial mission to “build a financial planner workforce for the 21st Century”, which would focus on 3 key pillars, including:

- Establishing an Academic Home for the profession (to support the growth of research on financial planning),

- Fostering increased Diversity and Inclusion efforts (given long-standing challenges in the lack of gender and racial diversity of CFP professionals), and

- Developing a “NextGen Pipeline” to attract more young people to the financial planning profession.

Recognizing that, in practice, one of the biggest blocking points to growing the number of CFP certificants has simply been a lack of awareness of what financial planning even is, to begin with (and how it differs from media depictions of financial salespeople and movies like “Wall Street” and “The Wolf Of Wall Street”).

Notably, CFP Board’s Center for Financial Planning is technically not an independent entity of CFP Board; it is simply an internal division within CFP Board, albeit one that was established to be funded independently through a combination of contributed income from individuals within the profession, and some (in some cases very substantial) corporate sponsorships.

Over the years, the Center has run a wide range of initiatives around its 3 core pillars. In the domain of developing the professional body of knowledge, this has included launching its Financial Planning Review journal for more academic financial planning research and a program to teach CFP Board-registered program instructors, along with a Client Psychology program at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and several books (e.g., Communication Essentials for Financial Planners: Strategies and Techniques). When it comes to diversity and inclusion, the Center has led a series of annual Diversity Summits, its “I Am A CFP Pro” campaign to highlight CFP professionals of color, along with an ongoing Women’s Initiative and a number of diversity research reports. And when it comes to Workforce Development, the Center has led the development of a number of CFP certification scholarship programs, a Guide to Financial Planning Career Paths that firms can develop, and a separate Career Guide for Financial Planners to teach future CFP certificants about the opportunities available in the profession.

Over the years, the Center has run a wide range of initiatives around its 3 core pillars. In the domain of developing the professional body of knowledge, this has included launching its Financial Planning Review journal for more academic financial planning research and a program to teach CFP Board-registered program instructors, along with a Client Psychology program at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and several books (e.g., Communication Essentials for Financial Planners: Strategies and Techniques). When it comes to diversity and inclusion, the Center has led a series of annual Diversity Summits, its “I Am A CFP Pro” campaign to highlight CFP professionals of color, along with an ongoing Women’s Initiative and a number of diversity research reports. And when it comes to Workforce Development, the Center has led the development of a number of CFP certification scholarship programs, a Guide to Financial Planning Career Paths that firms can develop, and a separate Career Guide for Financial Planners to teach future CFP certificants about the opportunities available in the profession.

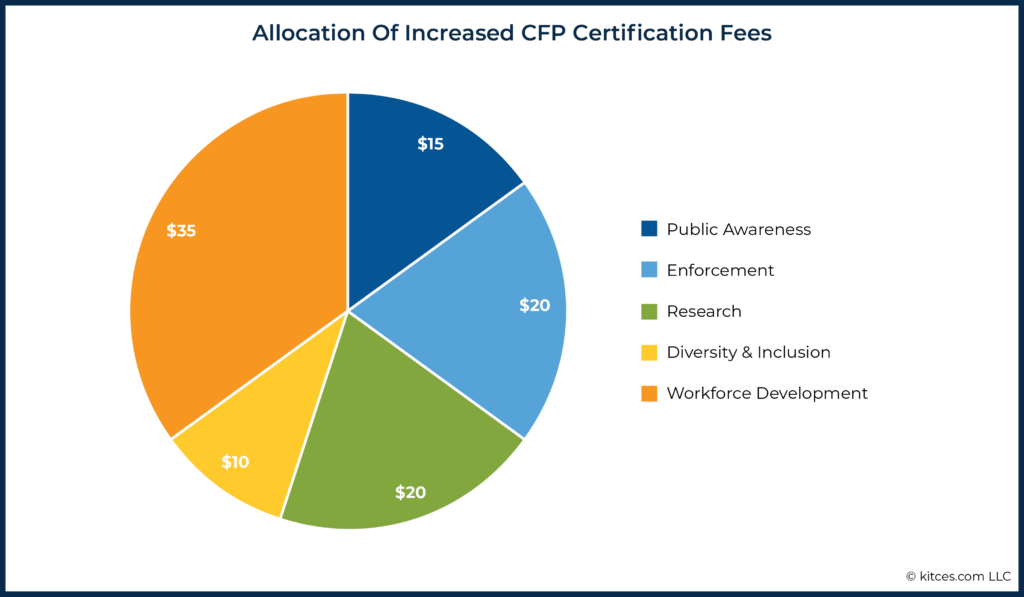

CFP Board Increases Certification Fees On All To Fund More Workforce Development

Earlier this year, though, CFP Board announced a substantial increase in its CFP certification fee… the bulk of which is earmarked for Center-for-Financial-Planning-related initiatives. Specifically, CFP Board announced that the annual certification fee would be increased by $100 – from $355/year to $455/year – to be allocated as $15 for its ongoing Public Awareness campaign, $20 for expanded Enforcement after its 2020 rollout of new Standards of Conduct, $20 for new Research to examine the impact of financial planning on clients, $10 towards Diversity & Inclusion initiatives, and $35 towards Workforce Development (to develop a national campaign that promotes financial planning as an attractive career for college-bound high school students). Meaning that $65 of the total $100 increase would be committed to Center-For Financial-Planning activities.

The announcement represents a major shift, as originally, when launched in 2015, the Center for Financial Planning was to be funded solely with donations from individuals, alongside corporate sponsors, with multi-million multi-year pledges from founding sponsors and a goal of raising $10M–$12M in donations over the subsequent 5 years. Yet, barely a year later, CFP Board introduced a $25 ‘voluntary’ contribution to the Center in its CFP certification renewal process… that CFP certificants were defaulted into, which was quickly unwound after the CFP professional community objected to the costs of the Center becoming a more-than-just-voluntary assessment.

But now, CFP Board is shifting from a voluntary fundraising contribution to a ‘mandatory’ assessment, by incorporating not just the prior $25/year but $65/year of Center-related activities (for Research, Diversity & Inclusion, and Workforce Development) directly into the annual CFP certification fee. Which across nearly 93,000 CFP certificants represents a more-than-$6M increase in CFP certification fees for programs that, while laudable, have been so far outside of CFP Board’s core purview that the organization had only ever funded it via independent fundraising in the past.

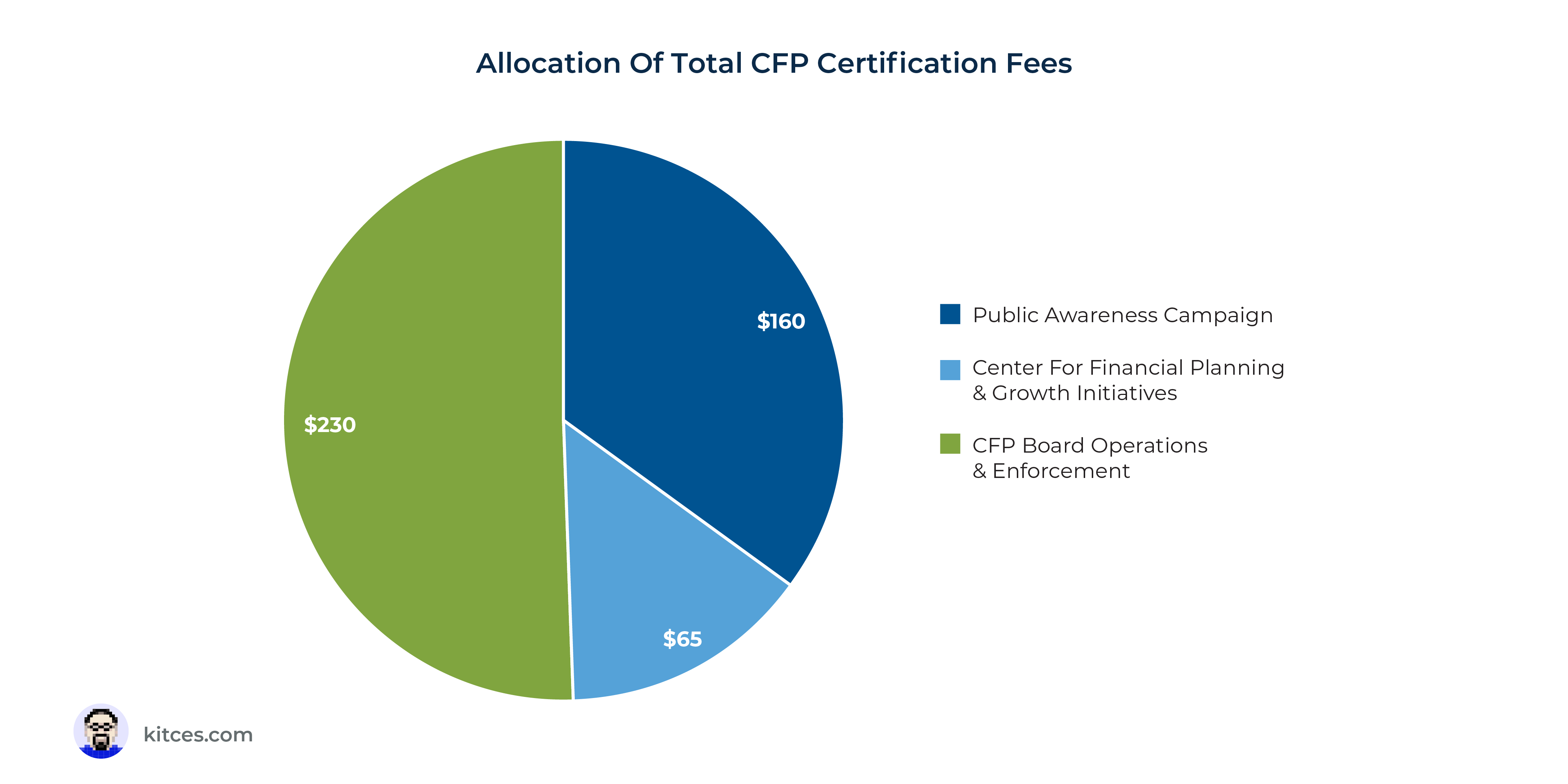

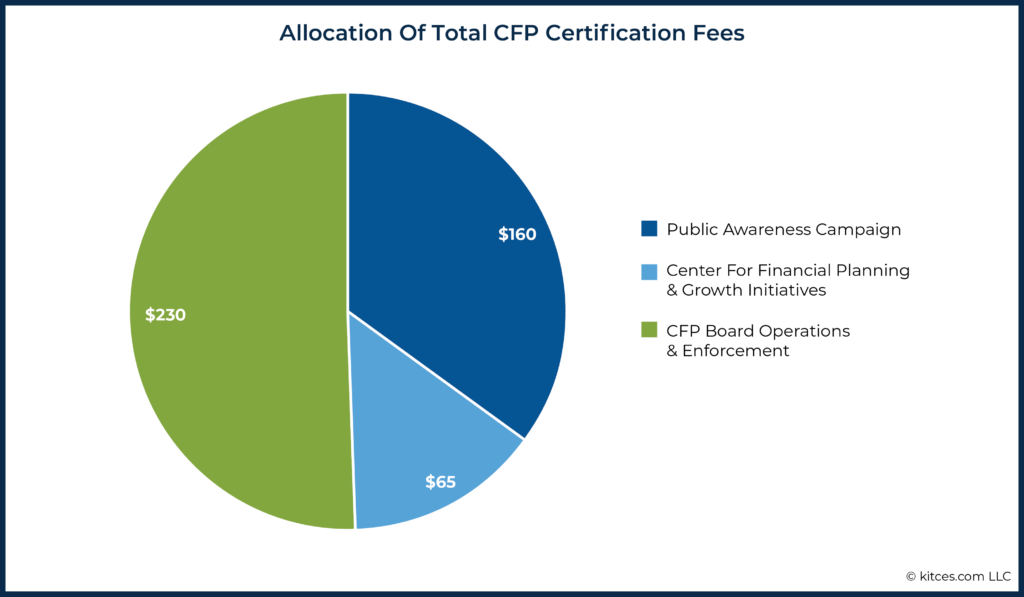

In fact, going forward, nearly half of the entire CFP certification fee will no longer be for the core operations of CFP Board. Instead, it will be allocated to its ‘other’ growth initiatives, including its Public Awareness Campaign and its Workforce Development (and other Center-for-Financial-Planning initiatives).

To some extent, this is concerning simply because barely half of CFP Board’s annual certification fee even covers CFP certification itself anymore, while the rest is focused on programs that perpetuate CFP Board’s own growth. Though, to be fair, all CFP certificants benefit from public awareness of the marks (it was popular amongst CFP certificants from the start more than 10 years ago), and the more CFP certificants there are (as CFP Board expands the ranks of CFP certificants), and the more that consumers have good interactions with CFP professionals, the better it is for the credibility of all CFP certificants.

Where Will All The New Students Seeking CFP Certification Go After Graduation?

While growth in CFP certificants can benefit all CFP certificants, the community of CFP professionals reasonably can and should still want to see what CFP Board is doing for non-operating assessments that have effectively doubled the cost of CFP certification.

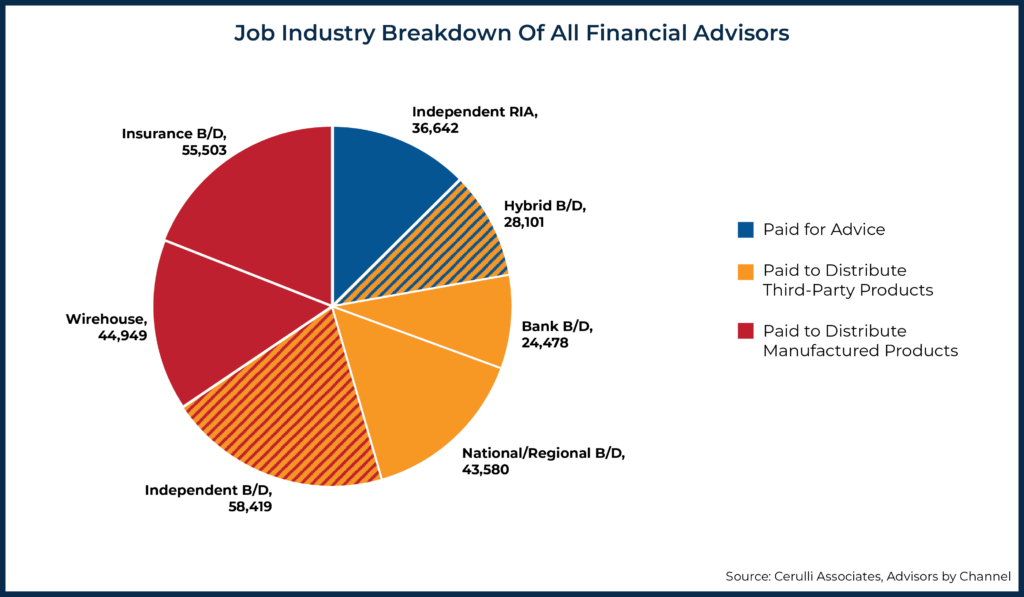

Especially when it comes to programs like Workforce Development… given the reality that the overwhelming majority of new entrants to the profession will still be likely to go into sales roles at product manufacturers, as those are still the companies that are trying to – and have to, because of their high-attrition model focused on marketing – hire the bulk of new industry entrants. Consequently, companies recruiting candidates for product sales roles are still prominently visible at career fairs and recruiting events for CFP exam and education programs, and literally have the overwhelming majority of job openings, given that the bulk of all advisor jobs are at product manufacturers (insurance companies and wirehouses) and distributors (broker-dealers), and not the RIA community that actually ‘sells’ (and charges for) financial planning advice.

Which is concerning… as, again, many of those – particularly the product manufacturers – are the companies that most often have sales roles with 80%+ attrition rates that they have maintained because, as a marketing strategy, high attrition is actually still quite profitable for product manufacturers!

In other words, CFP Board’s new Workforce Development initiative, in an effort to expand the ranks of CFP certificants by attracting new college-bound talent to the industry, appears to have unwittingly positioned itself to facilitate the high-churn recruiting strategy of product manufacturers. As the largest manufacturers are positioned all by themselves to hire more than 100% of all new recruits that CFP Board’s initiatives attract (given that CFP Board passes only 4,000–5,000 through the CFP exam every year, while single product manufacturers may hire that many new high-attrition advisor roles every year at just one company, not to mention what all of them hire in the aggregate!).

Even as the overwhelming majority of those recruits will likely be gone in just a few years… in a manner that is still profitable for manufacturers, it is a substantial loss for the CFP community’s now-forced funding of CFP Board’s program.

Lack Of Guidance In CFP Board’s Career Guide About The Risks of Failure

Unfortunately, CFP Board arguably may be amplifying the problem with its own Career Guide, which, in its discussion of “Financial Planner Compensation Methods”, only states that:

Other companies elect to compensate their financial planners (or at least their senior financial planners) based on a percentage of the revenue they [financial planners] generate. This payout method rewards productivity and business development success. The most significant risk with the payout method resides with new advisors. In the early years when professionals are still establishing their reputations and client bases, income may be quite low, though they may achieve much higher levels of income in the mature stages of their careers than they could with a salary. -CFP Board Career Guide

In essence, CFP Board’s explanation of salaried versus revenue-/commission-based compensation roles merely emphasizes that commission-based income is lower initially for more upside in the long run… without also acknowledging that commission-based roles also have drastically higher failure rates, and that the companies hiring into such roles even have a financial incentive to see high attrition and only a small subset of the ‘best’ business developers succeed. (Which is a great opportunity for those naturally skilled at business development… but a severe risk to CFP Board’s own Workforce Development program for the rest of the candidates seeking CFP certification that are never told about the risks of taking such a path in the first place.)

In the past, this dynamic wasn’t necessarily as problematic because CFP Board’s Workforce Development initiatives at the Center for Financial Planning were funded by a number of product manufacturers themselves who paid to sponsor its efforts – which means at least if their efforts resulted in higher attrition of candidates for CFP certification, the cost was primarily borne by the companies that caused the attrition to begin with.

But now, CFP Board is charging all CFP certificants to engage with its Workforce Development program, for an aggregate of 92,500 CFP certificants × $35/year = $3.2M per year… even as, in all likelihood, the bulk of the hiring will be done by the firms that cause the highest turnover and retention that created the shortage of young talent in the first place! And CFP Board and its Career Guide still aren’t even warning candidates of the high-failure-rate risks!

A More Data-Driven Approach To CFP Board’s Workforce Development Initiative

So given the substantial risk that CFP Board’s increase in certification fees may unwittingly fund the marketing efforts of product manufacturers instead of an actual long-term expansion in the number of financial planners (who can become CFP certificants), what should CFP Board do?

A Proposed Study On Students Graduating From CFP Board Registered Programs

First and foremost, if CFP Board wants to allocate dollars to Workforce Development with a strategy of building awareness in college-bound high-school students to lead more of them into CFP Board-approved education programs and become future financial planners, it needs to determine and demonstrate that young people who enter CFP Board-registered programs actually do end out becoming CFP certificants in meaningful numbers.

For instance, CFP Board might commission a study that works with 6–12 of the largest CFP Board-registered programs (which could amount to 1,000+ students) to do a comprehensive student-by-student analysis of all the graduates from 3 years ago. Where did the students actually end up? How many students in each program actually took an industry job after they graduated? What companies were they hired into? Of the various companies (or industry channels) that they were hired into, how many of each are still in the industry 3 years later? And how many of them ultimately got their CFP marks now that it’s been 3 years (and they had a chance to complete the experience requirement for CFP certification)?

By doing a focused cohort analysis that tracks down every student in the graduating cohort across a material sampling of programs, CFP Board can see who took which jobs and who remained in the industry or not (much of which can actually be tracked publicly from LinkedIn pages and, for most people who joined/stayed in the industry, from BrokerCheck/IAPD if they took any kind of advisor job that required registration/licensing). They can also determine whether boosting the flow of young people into CFP Board-registered programs will meaningfully expand the advisor workforce in the coming years, or just increase the volume of advisor recruits that succumb to the churn of product manufacturers looking to gather lists of 100 friends and family for their own marketing purposes.

Perhaps, in the end, it will reveal that rising candidates for CFP certification have already realized the risks and challenges of sales-centric jobs, and are effectively finding their way to more stable career paths with higher retention. Or alternatively, perhaps it will turn out that the only reason CFP Board already hasn’t been growing more is that sales jobs from product manufacturers with high attrition rates have been churning the majority of all graduates in the first place, and the real challenge is not attracting more young people, but providing them a better education than what CFP Board’s Career Guide explains about the real attrition risks of choosing certain industry channels over others!

Reporting Channel Failure Rates In CFP Board’s Career Guide For New Planners

Once CFP Board can take a more data-informed approach about whether and how often students who graduate from CFP Board-registered programs actually remain as long-standing advisors (and future CFP certificants), and what career choices really lead to increases in success (or failure) as a new financial advisor, it can and should update its Career Guide to reflect these realities.

As again, despite drastic differences in the success and failure rates that have long existed between the industry channels – where salary-based jobs that involve supporting clients with recurring revenue, from AUM-based independent RIAs (and increasingly hybrid B/Ds) to large platforms like Vanguard, Schwab, Fidelity, and Merrill Edge that are building out their own centralized platforms with a large volume of CFP certificants to service their existing clients, create far more stability than ‘eat-what-you-kill’ sales-based jobs – CFP Board’s current Career Guide says nothing about the relative risks and significant difference in failure rates between the channels.

After all, if the reality is that more than 80% of those who take sales jobs are gone in 3–5 years, and 80% of those who take service jobs may still be in the industry in 3–5 years, shouldn’t rising students know that? Not that there’s anything wrong with someone who is excited to prospect and sell and do business development, finding their way to a product company that will require their natural ability there. In fact, ideally, the Career Guide should highlight that those with the best natural business development skills (or those who have a particularly strong natural market to sell to) will thrive in such channels.

But that only works with a candid reflection of the associated risks and failure rate and more clarity about the relative risks between the channels. Which CFP Board’s Student Study could determine with real data, and the Career Guide could then reflect. Which, ironically, would simply make CFP Board’s own Workforce Development efforts more successful by appropriately guiding graduating students to truly understand the different risks between the channels!

Delay Workforce Dues Increase Until CFP Board Can Demonstrate Responsible Deployment

Until this work is done – that is, an effective study to show where students in CFP Board-registered programs actually go after they graduate, to understand whether increasing the flow of students will result in a larger advisor workforce or just a higher volume of advisor churn, and updates to CFP Board’s Career Guide to help students navigate those risks – CFP Board should delay the increase of at least the Workforce Development portion of its new certification fee.

As simply put, CFP Board and its Board of Directors have an obligation to demonstrate that it will be an effective steward of the additional certification fees it is assessing, particularly if the Center for Financial Planning is moving from a fundraising model (where the corporate sponsors who stand to benefit are paying themselves) to a broad-based CFP-certificant-fee-assessment model (where CFP certificants are paying for an initiative that may disproportionately benefit product manufacturers over actual Workforce Development).

Especially when recognized, in the broader context, that nearly half of all the CFP certification fee being assessed by CFP Board is no longer actually for CFP certification anymore, but for the organization’s own growth initiatives, to expand public awareness of CFP certification to make it more attractive for advisors to pursue, and to workforce development to outright increase the number of future CFP certificants. Which, again, can still be beneficial for all CFP certificants – arguably beneficial enough to merit a fee increase for all CFP certificants to support the growth of the marks – but only if CFP Board can show a strategic plan with a reasonable likelihood of success.

After all, as it stands today, CFP Board’s new certification fee of $455/year will amount to nearly $42M of annual revenue… of which about $21M supports 92,500 CFP certificants, with the other $21M supporting what has historically been a growth rate of only about 4,000–5,000 new CFP exam takers every year. Which suggests that thus far, ‘growth’ remains relatively inefficient for CFP Board, and might be improved with an even more data-driven research-based approach to where dollars are best deployed so CFP Board isn’t simply funding a leaky Workforce Development sieve that primarily benefits product manufacturers, and not the CFP Board’s own growth goals… nor benefitting the CFP certificants who are footing the bill!