By Lambert Strether of Corrente

The International Labor Organization (ILO) has published a report (PDF): “A global analysis of worker protest in digital labour platforms” (hereafter “Worker Protest”). Since it’s always worthwhile taking a look at the precariat — not to mention the international working class — I thought I’d take a look at it and summarize the high points for you. But first, I’ll take a look at the ILO, which I realized I knew nothing about when I read it was founded in 1919 (that is, of League of Nations, not United Nations, vintage). From the ILO’s About page, “How We Work”:

The unique tripartite structure of the ILO gives an equal voice to workers, employers and governments to ensure that the views of the social partners are closely reflected in labour standards and in shaping policies and programmes.

No contradictions there! And Mission and impact:

The main aims of the ILO are to promote rights at work, encourage decent employment opportunities, enhance social protection and strengthen dialogue on work-related issues.

Of course, it’s a minor miracle that something called “The International Labor Organization” is even permitted to exist. The ILO did win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1969. From their acceptance speech:

What we in the ILO seek to achieve through all our programmes is the elimination of poverty, hardship and privation which weigh so heavily upon the dispossessed peoples of this earth. Our Organisation is central to the international effort to raise their standards of living, to improve their living and working conditions, and to secure to them fundamental human rights, to the end that they may take their place in society as free, dignified and self-governing people. To the extent that our efforts, and those of governments and members of the international community, are successful in achieving these ends, the basis will be laid for a stable and durable system of world peace. But in making this statement we have no illusions about the difficulties which stand in our way.

Indeed, the ILO is not without its critics. “Emerging Challenges of International Labour Organization” at SSRN criticizes ILO’s deliverables:

Historically appreciated for its formal standard-setting activities, the nature of the ILO’s outputs and the extent to which they are authoritative has evolved significantly over recent decades. The ILO has increasingly relied on ‘soft’ governance instruments as opposed to legally binding standards. The ILO’s Recommendations, Declarations, and overarching policy frameworks are examples of instruments that move away from traditional forms of legal authority. They are characterized by relatively lower degrees of obligation, precision and delegation and help overcome practical problems like the inability to reach broad acceptance of legally binding commitments and their associated high political costs. For critics, however, such instruments represent a weakening of legally binding commitments and a dangerous turn to more aspirational and promotional approaches to achieving broader progress in labour rights protection.

And:

The ILO’s current lack of representativeness in its decision-making processes is untenable in the long run. and over 90 per cent of micro- and small enterprises worldwide.

Perhaps, then, if the ILO’s unique tripartite structure were more closely realigned to the actually existing international working class, its deliverables would not be quite so toothless. “Worker Protest” could be taken as a step in that direction.

Now let’s turn to the report proper. I don’t think I’m doing it justice! The report is well-written and well-researched; the prose is not leaden, but it’s very dense. I do think organizers and others interested in the dynamics of the international working class will find it repays careful reading. This post will quote great slabs from “Worker Protest,” thrown into three buckets: methodology, data, and collective organization.

Methodology of “Worker Protest”

Here is the scope of “Worker Protest”, and its methodology. From the Introduction, pp. 7-8:

The growth of platform worker protest has been remarkable. Despite widespread predictions that platform models would render worker organization impossible (Vandaele 2018), platform worker protests have made headlines across the globe. Nevertheless, platform worker protest also presents researchers with considerable challenges. It does not fit easily into established frameworks of labour relations. Formal employment and collective bargaining are rare, and rates of unionization low (ILO 2021a). Some platform workers are organized in traditional unions – most commonly in parts of Europe – but there has also been a growth of much smaller, new unions. Other platform workers – notably in the global South – organize informally in ad hoc groups drawn together around specific grievances. As a result, platform worker discontent is difficult to capture by conventional means. While platform worker protest features in news media coverage and case study research, there is little understanding of the wider picture.

So, impressively, the “Worker Protest” authors built a database:

To overcome some of these difficulties, and as a contribution to building a more global understanding of platform worker protest, we have created a unique database: the Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest (Joyce et al. 2020; Trappmann et al. 2020). This database gathers data on platform worker protests from and is based at the Centre for Employment Relations, Innovation and Change at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom. Drawing from the Leeds Index, …. Our analysis considers where and how often platform workers engage in protest activities; what issues are driving their protests; and what methods of protest and forms of organization they use.

Readers may recall that PayDay Reports undertook a similar project for United States Strikes during Covid; I have done a similar project in a previous incarnation. The PayDay Reports map was tip-driven; mine, like “Worker Protest,” was media driven, which involved a lot of reading and data entry, but more or less fell out of my normal blogging activiity. (These are hard projects to keep alive because funders don’t do infrastructure.) “Worker Protest” has a potential difficulty in that it depends on online reporting, which filters out those who are not online; however, worker in the “Global South,” at least, are extraordinarily online, via their phone, which in any case are how they get their gigs.

The “protest” lens is a methodological issue as well. From pp. 9-10:

We adopted a focus on protest events as an indicator of labour unrest in platform work. In so doing, we drew on insights from social movement research. As della Porta and Diani (2015, 3) explain, “social movement studies … stand apart as a field because of their attention to the practices through which actors express their stances in a broad range of social and political conflicts”. Social movement research has also often featured labour and trade union struggles (for an overview, see Silver and Karataşlı 2015; see also Gamson 1975; Shorter and Tilly 1974). (Millward and Takhar 2019; Silver and Karataşlı 2015; Alimi 2015; Tarrow 2015; Krinsky and Mische 2013; Wang and Soule 2012). By contrast, industrial relations research tends to apply established, standard measures across many 08 ILO Working Paper 70 different historical and institutional settings: measures such as official strike data, union membership and collective bargaining coverage. While this approach brings benefits in terms of consistency and comparability, it also carries disadvantages that become especially problematic when trying to understand forms of worker contestation that fall outside these conventional, institutional forms. In platform work, with little formal employment, low levels of union membership and very little stable collective bargaining, the standard measures are obviously at a disadvantage. Consequently, the social protest approach offers important benefits for understanding labour unrest in platform work, where significant levels of worker protest take place outside conventional frameworks.

(I find the “protest’ lens very congenial, because I tend to follow occupations and insurgencies by looking at “methods of struggle.”)

Data from “Worker Protest”

Here’s a map of worker protests, on pp. 18-19:

That’s rather a lot. The authors comment:

When we look at overall frequencies across regions over the study period, there was a relatively even spread across Asia and the Pacific and across Europe and Central Asia, with close to 400 protests in each region. Between 200 and 250 protests were recorded for North America and Latin America and the Caribbean, with much lower numbers in Africa and the Arab States.

(It’s interesting to see the concentration of protests in China, and to recall the stories about PMCs in China being unable to get their food delivered because of lockdowns, and the lack of stories about the workers who would have delivered that food.) The map doesn’t show which protests are against a single platform (e.g., Uber) and which are against multiple platforms (Uber, Grab, Deliveroo). The authors comment:

Of the 1,271 protest events that we found, 67.2 per cent targeted a single platform, while 32.8 per cent targeted multiple platforms. The multi-platform type of protest features in previous case study research and seems to reflect the way in which individual workers often work through multiple platforms. It is often assumed that solidarity across workers at different companies is difficult to generate. Viewed historically, however, solidarity between workers in the same occupation, especially in a shared geographical space (e.g. city or region) is not unusual. Indeed, as authors such as Ruth Milkman (2020) have noted, When we looked at multi-platform protests, the driving issues and types of protest were broadly similar to those in single-platform protests (we discuss this issue later). In one interesting divergence from other findings, however, we found that multi-platform protests were unevenly spread, being far more common in Latin America and the Caribbean (50 per cent) followed by Asia and the Pacific (26.6 per cent) and Europe (20.7 per cent). Reasons for this variation remain unclear.

32.8% percent multi-platform protests — by definition solidarity across workplaces, however virtual — strikes me as encouragingly high.

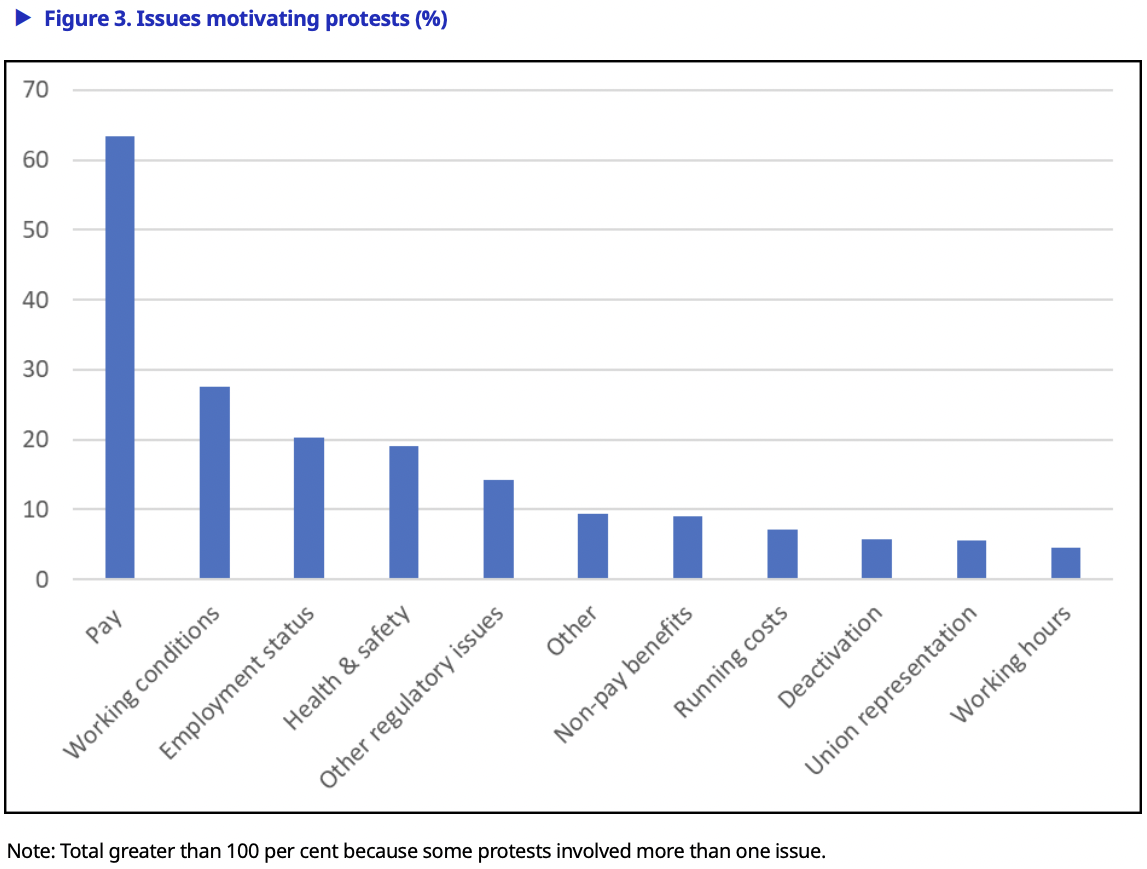

Here is a chart of issues driving the protests, pp, 21-22:

Wages and working conditions. Shocker! The authors comment:

[P]rotests were motivated by a wide variety of issues. However, by far the most prevalent cause, identified as a factor in 63.8 per cent of protests, was grievances over pay. The prevalence of pay as an issue driving platform worker discontent is one of our most striking findings, in sharp contrast to the emphasis in previous literature on issues around algorithmic management. In our findings, protests by platform workers are far more likely to be driven by platform company decisions about levels of remuneration than by day-to-day issues with the operation of algorithms.

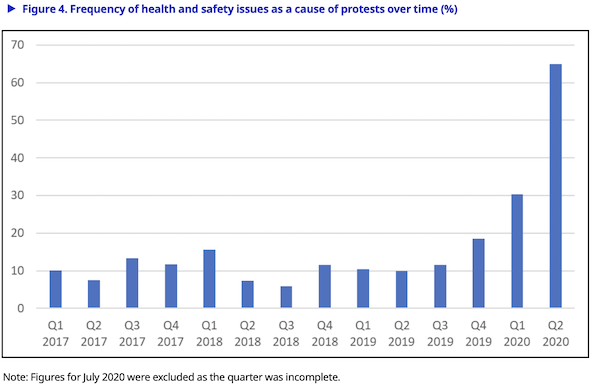

And when Covid comes along:

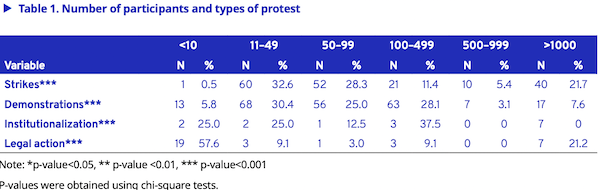

Here is a chart of tactics used and numbers involved in protests, pp. 23-24:

The authors comment:

[W]e found wide variation in the number of workers involved. The modal range for participant numbers is 11–49, followed by 50–99. However, we counted 65 cases in which more than 1,000 workers were involved. An examination of data on the duration of protests indicates that they usually lasted less than 24 hours, suggesting that platform labour protest generally tends to comprise mainly very short actions. …. . With regard to the number of participants per protest, the numbers of participants both for strikes/log-offs and for demonstrations are noteworthy. In many cases, activists were able to organize more than 100 individuals. In some 50 cases of strikes/logoffs, more than 500 workers participated.

Collective Organization of “Worker Protest”

Are unions involved? How much organization was bottom-up and “spontaneous”? The authors comment (pp. 23-24):

Regarding the collective organizations involved in worker protests, . These groups of workers were the key form of collective organization in platform worker protests across the globe, significantly outstripping union organization, either traditional or new. In 48.3 per cent of the protests that we identified, a group of workers acted without the involvement of any other organization. Indeed, in our data, protests where self-organized groups of workers were not involved were far less common than cases where they were. This important finding reflects how platform worker protest is driven by self-organization among workers, more so than by union organizing efforts, however important these might be in some settings.

Seeing this comment on union leadership in the United States from Upstater, I can’t help but feel there’s something to be said for “self-organized groups of workers.” OTOH, it’s hard to see where that self-organization leads, beyond resolution of the immediate grievance. More:

Clearly, this finding rebuts the still widely held but mistaken belief that unions cause labour unrest.

Ouch. Dry, very dry. Nevertheless, union involvement does have distinctive features and some advantages for workers:

Where we did identify trade union involvement, traditional unions were present in 18.3 per cent of protests at the global level, and new unions in 13.1 per cent, giving a total of 31.4 per cent of cases in which some form of trade union organization was involved…. Given the significant focus on new unions in much of the case study research, On the other hand, given the huge disparity in size and resources between new and traditional unions, the fact that their presence is in any way comparable is truly remarkable. It is difficult to think of comparable examples from other sectors. Indeed, the prevalence of ununionized protest in platform work is reminiscent of much earlier periods of pioneer organizing among new groups of workers, such as the early days of the mass production industries (see Darlington 2013). (Joyce and Stuart 2021; Cant 2020). These features of union organization in platform work coincide to break the close link between union membership and collective action, which is a standard assumption of established industrial relations perspectives. In platform work, the relationship between collective organization, union membership/ non-membership and collective protest is much more fluid and dynamic than most settings where industrial relations are studied. As a result, the tendency of platform workers to self-organize, first noted in case study research, is strongly supported by our findings. The picture that emerges is one whereby platform workers first organize themselves and later may look towards established organizations – of various types – to aid their efforts, and may sometimes even move from one organization to another in search of a better fit (cf. Aslam and Woodcock 2020). Even these basic patterns vary considerably across different regions (see below). Moreover, labour organizing among platform workers is still in its infancy, and the final form(s) that this highly dynamic process might take remain unclear.

Conclusion

The authors conclude, pp. 34-35:

Our findings suggest both notable similarities and differences among platform worker protests across the world. The analysis shows that and tends to be the subject of protests in all regions of the world. Indeed, the overwhelming presence of pay as the major cause of platform worker protest suggests that . Moreover, while much scholarship places emphasis on forms of online activity such as the subversion of algorithms, our findings show that more traditional methods, such as strikes and demonstrations, are also widely used in platform worker protests…. At the same time, some genuinely distinctive aspects of platform work became apparent through analysis of our data. In particular, the number of protests that were directed at multiple companies is a distinctive characteristic of platform work, which likely reflects the nature of platform labour markets, where workers often rely on multiple platforms to earn a living. It also suggests that .

Personally, I find this conclusion, and the report in general, very hopeful (and in a time when we need all the hope we can get). It also shows that the same trends that are bringing us Starbucks and Amazon organizing in this country are worldwide, which is another sign of hope (and maybe for the ILO, too). Carry on!