My latest piece for Fortune compiles a lot of the work I’ve been putting together here on the blog — how long bear markets tend to last, the two types of bear markets, bear markets vs. recessions and how investors should approach down markets depending on where they are in their investing lifecycle.

*******

The technical definition of a bear market in stocks is a drawdown of 20% or worse from peak to trough.

At its nadir this year, the S&P 500 was off nearly 24% from its all-time highs reached in early January. So we are in a bear market.

Going back to the end of World War II, the U.S. stock market has experienced 13 bear markets (including the current one). In the previous 12 bear markets, the average loss was –32.7%. It took the stock market an average of around 12 months to go from the peak of the market to the bottom. It then took roughly 21 months on average to go from the bottom back to the previous peak.

So the average time for a roundtrip in a bear market to make it back to breakeven has been less than three years over the past seven decades or so.

As with all historical market data, there can be a wide range of results around those long-term averages. Each bear market is different, but investors can glean some lessons by looking at past market crashes.

Here are some lessons from historical bear markets:

How long bear markets last

A bear market in stocks can inflict pain on investors in two different ways: (1) losses and (2) time. The percentage decline in the stock market is where most of that pain comes into play, but the length of bear markets can add insult to injury.

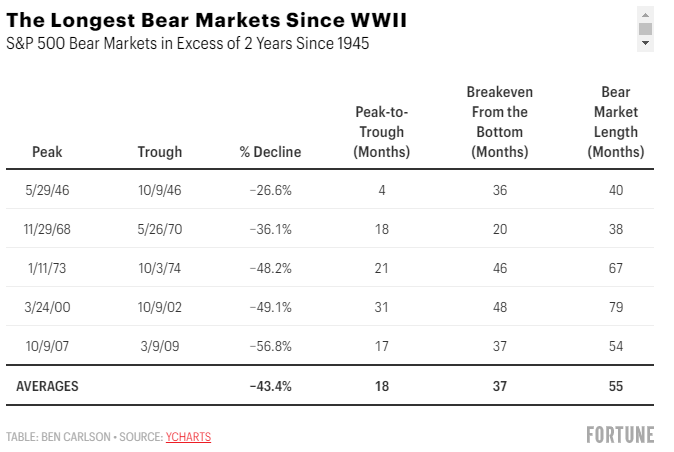

Here is a list of the longest bear markets in U.S. stocks since World War II:

It can take a long time to break even in the stock market during a market crash situation. It took four and a half years for the stock market to perform a roundtrip following the 2008 financial crisis. It took nearly seven years to break even after the bursting of the dotcom bubble in the early 2000s.

Research shows losses sting twice as much as gains bring us joy, so the longer you are underwater in the market the more suffering involved. That suffering can often lead to mistakes by selling at the worst possible moment.

Patience is a virtue during bear markets because sometimes it takes stocks a long time to make up for their losses.

Recovering from stock market crashes

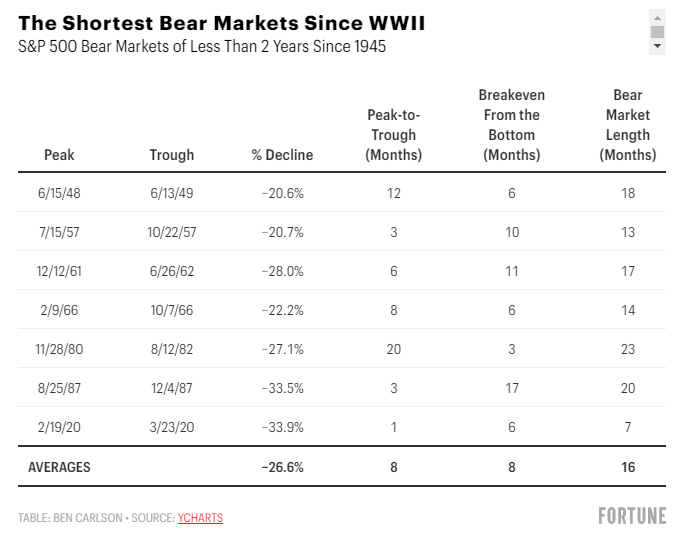

It’s also true that some bear markets are over in a hurry. The Corona Crash in early 2020 at the onset of the pandemic is a perfect example.

The S&P 500 fell almost 34% in just 23 trading sessions, the fastest bear market from an all-time high in more than 90 years. But that crash lasted just one month from peak to trough. It took just six months from the bottom for the stock market to break even. In fact, the stock market was up 100% from those lows in just 15 months.

There have been seven bear markets since 1945 that have lasted two years or less in terms of the time it takes for the stock market to make up for all of its losses:

The 2020 recovery was an outlier, but you can see there have been four other bear markets historically that have made investors whole in a year and a half or less.

This is what makes investing in the stock market so challenging at times—when you’re in the midst of a bear market, you don’t know if it’s going to be over in a hurry or lead to a situation that feels like death by a thousand cuts.

Bear markets vs. recessions

There are a number of people who feel the U.S. economy is either already in a recession or fast approaching an inevitable economic contraction.

I understand this sentiment. Inflation is at a four-decade high. Since 1945, there have been nine times when the inflation rate spiked above 5%. Every single one of those inflationary spikes was followed by a recession. It feels like the only way to stop price spikes is to slow demand in the economy.

It’s certainly possible that will be the case this time around as well. In fact, it seems like the stock market is already pricing in a recession.

While recessions are almost always the cause of a nasty bear market in stocks, a bear market does not always equate to a recession. In the summer of 1946, the stock market fell 27% with no recession on the horizon for a number of years. In 1966, the stock market fell 22% without a slowdown in the economy. Perhaps the most famous example of a stock market crash without a recession came in 1987 when the stock market had its biggest one-day fall in history on Black Monday. The stock market was down more than 30% in less than a week. Many people at the time assumed the stock market was signaling a depression. Yet no slowdown ever came despite that crash.

Predicting the timing of economic cycles is not easy. Even the stock market gets it wrong from time to time.

Bear markets vs. bull markets

The good news about bear markets for U.S. stocks is they all come to an end eventually. Some are longer, some are shorter, some are deeper, and some are shallower, but every crash in the history of U.S. stocks has been followed by new all-time highs at some point in the future.

So how should investors think about the current downturn? Risk is in the age of the beholder when it comes to investing.

If you are retired or fast approaching retirement, you don’t have nearly as long to wait out an unpleasantly long bear market. Diversification and liquidity are your friends when you don’t have as much time or income to look forward to as an investor. Cash and short-term bonds are a drag on long-term returns but they can ensure that you won’t be out of luck when you need to spend your money in the short term.

If you are a young person with many years or even decades ahead of you, this bear market and all future downturns should be looked at as an opportunity. If you are going to be a net saver in the years ahead, you should be thankful for stock market crashes. They allow you to pick up stocks on sale at lower prices, lower valuations, and higher dividend yields.

You just have to have the discipline, patience, and planning capabilities to ensure you can periodically buy stocks even when it doesn’t feel right.

Bear markets are never fun to live through because no one likes to see their portfolio go down in value. But stock market downturns are a feature, not a bug. If stocks didn’t crash on occasion they would not offer such wonderful returns over the long haul.

Originally published at Fortune.