With a global energy

price hike generating high inflation in most countries, and central

banks reacting by raising interest rates, comparisons with the 1970s

are in fashion. The 1970s have for a long time been seen by the

political right in the UK and US as the chaos before the calm, where

the calm is the advent of neoliberalism. For much the same reasons, a

common refrain on the left is that the 1970s were a lot better than

what came later in many ways. A good example of the latter is a

recent article

by Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy. While taking the kind of holistic

view he does there has its merits, it also frames the debate as an

answer to the question ‘1970s: good or bad?’, while reality is

more complex than that. In this post I just want to focus on just two

issues: inflation and trade unions.

Tooze says that successfully controlling inflation (through independent central banks) was a victory for conservative politics. Historically inflation produces winners (borrowers) and losers (savers), and so controlling inflation was a victory for savers. In addition high inflation goes with unpredictable volatility. Inflation started at 5% in 1970, rose to over 25% in the mid-seventies, then fell to below 10% only to rise again in the early 1980s. So those who prefer stability, like most business owners, will also prefer low and stable inflation. But the constituency that enjoyed the high and variable inflation of the 1970s is both small and lacks political representation.

The high

and variable inflation of the 1970s was generally unpopular, and as a

result no political party campaigned for it, just as no political groups today are arguing that the current increase in inflation should continue. I think it would be fairer to say that successfully controlling inflation is generally popular, rather than characterise it as a victory for conservative forces. There are many reasons

why high and variable inflation is unpopular. While economists often

focus on the costs of unwarranted relative price dispersion, what was

far worse in the 1970s was heightened social disruption. Days lost in strikes reached a post-war peak in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Strikes are costly because of lost pay and production, but also because

of the social dislocation they can cause.

The political right likes

to slide from this observation to suggest that strikes are always the

fault of workers, or even worse ‘trade union barons’. Their

predictability on this makes their claim

to be ‘the party of the working class’ risible.

Many on the left do

the opposite. Strikes, after all, appear to be the archetypal battle

between workers and capital. Unfortunately this overlooks one key

point, which is that firms also set prices. As a result, when

inflation is widespread strikes are not a battle between wages and

profits for their share of any surplus, because employers can often

recoup their share of the surplus by raising their prices. The

reality is that strikes represent the breakdown of negotiations

between two sides, where either workers, employers, both or none can

be to blame. Such breakdowns tend to be bad for both the employers

and employees involved, and often for many who use the products or

services they create. High and volatile inflation goes together with a high number of days lost through strikes for obvious reasons.

The unfortunate

reality that is often missed on the left, but which is understood by

most macroeconomists, is that a large increase in global energy

prices have to lead at some point to a corresponding reduction in

real wages (compared to what they otherwise would have been), for

reasons I discussed here.

Governments can and should act to cushion that effect for those on

low incomes (and more widely if higher commodity prices don’t

redistribute from consumers to those working to produce commodities

but instead redistribute

to the profits of commodity producing multinationals),

but unless higher energy prices are known to be temporary there is no

reason to permanently cushion that impact for all workers, and good

reasons why they shouldn’t.

In these

circumstances, suggesting

all workers should aim to get nominal wage rises that match the level

of inflation is unrealistic, as most will not. Attempts to do so will

just risk recreating what happened after the 1970s: very high

interest rates and a recession. Equally now is not the time for firms

to attempt to generate large increases in profits, because this too

invites a reaction from central banks. But the first is not a

cure for the second, except insofar as a recession hits profits as

well as workers. [1] (As the postscript to this post points out,

larger than average real wage cuts imposed by governments on public

sector workers are a completely different issue.)

For some on the

left, this refocuses the debate on technocratic and undemocratic

independent central banks. After all, if it wasn’t for higher

interest rates, we wouldn’t get a recession. Tooze writes:

“Independent central banks were not truly above politics; they were

the extension of conservative politics by technocratic and non

democratic means.” But, for better or worse, independent central

banks have a mandate to keep inflation near a target. If central

banks were not independent, it is very likely that politicians of all

stripes would set themselves similar inflation targets, and go about

achieving those targets in similar (although probably more erratic) ways.

Some of the dislike

on the left for independent central banks is because the cure to

excess inflation often involves an increase in the number of people

losing their jobs. But this has little to do with central banks per

se, and represents a more general dislike of using demand management to

control inflation, whether it’s through interest rates via an

independent central bank or a government using fiscal or interest

rate policy. The 1970s in the UK in particular represented a

prolonged experiment in attempting to control inflation without

imposing the costs of higher unemployment, and instead using a

mixture of wage and price controls and deals between governments and

trade unions. The result of this experiment was clear – it failed.

There is a more

nuanced criticism of independent central banks with low inflation

targets, which is that they replace the inflationary bias of the

1970s with a deflationary bias. This is the line Tooze takes,

although I think it needs pinning down more precisely than he does in

the article. We have no clear evidence of deflationary bias in the

1990s or early 2000s. In the UK, for example, underlying growth was steady at similar levels to the 1950s, 60s, 70s and 80s.

There is no reason why, in normal times, controlling inflation should

be deflationary, and no good evidence that it generally is.

However it may well

be the case that central banks, given the history of the 1970s,

overreact to similar external shocks to those that happened then.

David Blanchflower has rightly argued

that the Bank of England was too focused on raising rates following

higher commodity prices in the second half of the 2000s to notice the

impact the Global Financial Crisis was having. The ECB raised rates

in 2011 when commodity prices started rising after crashing during

the GFC, and the Bank of England nearly did

the same. Some might argue that central banks are

overreacting now because the dangers of a wage-price spiral are much

less than in the 1970s.

However it’s far

from clear to me that this shows some flaw in the idea of independent

central banks. Politicians, like independent central banks, are just

as prone to refight the last war. There are ways of dealing with this

deflationary bias without returning to high and variable inflation,

like raising the inflation target or changing

the target in other ways. Independent central banks with

inflation targets represented a positive response to the inflation of

the 1970s, and there is no reason why these cannot be improved if it

turns out that central banks are overreacting to inflation today. [2]

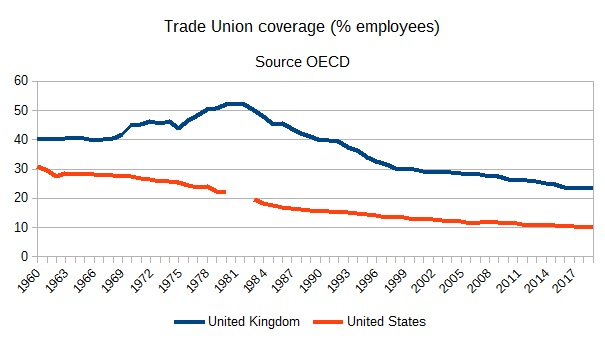

I noted earlier that

one reason why the left wants to question the image of the 1970s

pushed by the right is because the 1980s saw the beginning of the

neoliberal hegemony. In particular, it saw the start of a decline in

trade unionism in both the UK and US. In addition, and whether it was

a factor behind decline is not obvious, these neoliberal governments

substantially reduced trade union power.

But if it is the

case that we are less likely to get a wage-price spiral leading to a

severe recession today because unions are less powerful, isn’t that

a good thing? There’s an apparent dilemma here which many on the

left are reluctant to face. The dilemma is that there is an inherent

power imbalance between employee and employer in most workplaces and trade unions are important in redressing that imbalance. But is

it possible to have strong unions without also generating wage price

spirals following commodity price hikes?

International

experience suggests the answer may be yes. While trade union density

has declined in many countries in a similar fashion to the US and UK,

in others it has not.

Will these countries

suffer a worse wage price spiral, and therefore recession, than

elsewhere because of greater union coverage? If not, then the link

between widespread unionisation and the high inflation of the 1970s

is less clear cut than many on the right (and some econmists) like to

suggest. There is no dilemma if it is possible to have strong unions

that also recognise when real wages have to fall following higher

commodity prices.

[1] This is why

central bankers who extol wage restraint without also pushing profit

restraint should know better. In the current context both are

inflationary, and the only cure central bankers have for either is

the same: higher interest rates and a decline in economic activity.

There may also be more medium term concerns about rising mark-ups

that are possible because of monopoly or monopsony power in

particular sectors, but there are plenty of medium term remedies

available to governments to deal with those, like encouraging

competition (in the UK’s case, reversing Brexit), better regulation

and a stronger antitrust policy.

[2] There is a

stronger case against separating monetary and fiscal policy, which is

that it facilitates austerity. I make that case here,

although as I argue here

even that strong case ultimately fails.