Executive Summary

Financial planning is both an art and a science. While an advisor needs technical financial planning knowledge to create and implement plans for clients, soft skills that involve effective communication and relationship building are also crucial to both relate to prospects and clients and to understand their needs. Further, one of the most important qualitative ways an advisor can add value to clients is by helping them identify and select meaningful goals. And so, by asking the ‘right’ questions and building a bond with clients, an advisor not only ensures that their clients select appropriate goals, but also creates ties that will encourage them to remain clients for years to come.

As part of his Life Planning approach, George Kinder developed three questions that probe deeper into a client’s hopes, dreams, and fears, to help advisors develop more complete and impactful financial plans. The first of these questions asks clients to dream about their future and freedom, brainstorming how they would live their life if they were financially secure. The question is open and exploratory, creating the perfect environment for the client to provide more insight into their goals and priorities.

This approach to goal setting relies on social constructionism, a theory that suggests reality can be developed collaboratively. When advisors and clients work together through dialogue to develop a shared vision of the client’s dream life, both parties are better able to understand not only what the goal is, but also why it matters.

Notably, the goal-development process is not a quick one. Often, clients do not know what their goals are, or might struggle to articulate the details of their goals. For example, a client might say that their goal is to retire, but that doesn’t tell the advisor what the client wants their retirement to look like. But by using dialogue and engaging in the process of developing a socially constructed goal, the advisor may uncover what retirement really means for the client – the goals and activities they wish to pursue, how they want to spend their time, and how they envision their future.

Another benefit that comes from socially constructed goals is relationship stickiness. When goals are co-constructed between an advisor and their client, the desired outcomes are something that both parties uniquely and intimately share. And when an advisor co-constructs with clients, no other advisor will do!

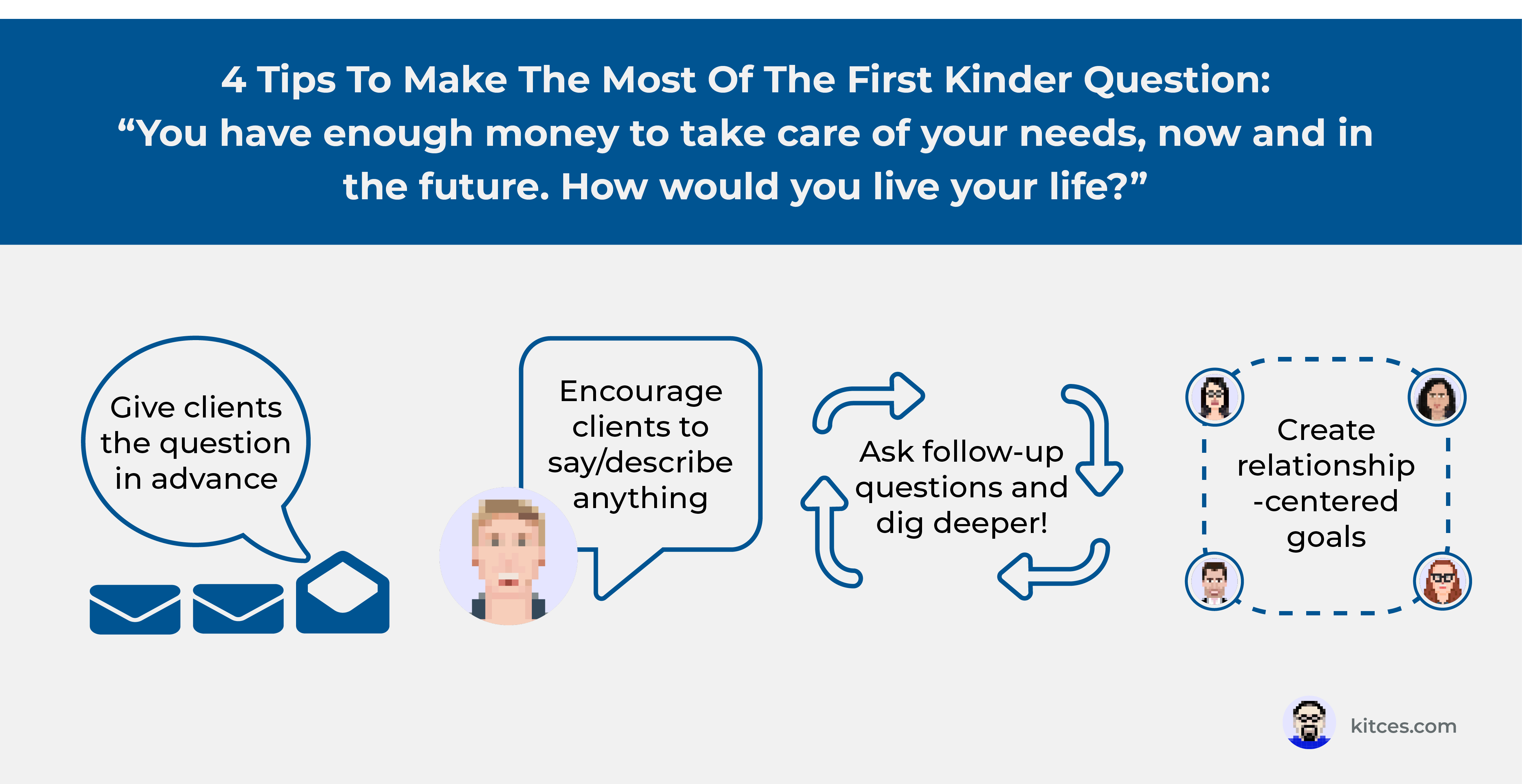

In practical terms, while Registered Life Planners typically bring up the Kinder questions with clients without warning (as they have extensive training to handle the ‘shock’ value of the questions), other advisors with no Life Planning training might consider giving clients advance notice so they can start to consider their answers and help both parties be more comfortable with the discussion. During the client meeting, it is important for the advisor to ask several follow-up questions, not only to keep the conversation flowing, but also to help clients clarify their goals. These questions could explore the client’s motivations, who else is with them when imagining their best life, and how their dream differs from their current situation.

Ultimately, the key point is that Kinder’s first question is a valuable tool for advisors to work constructively with clients to help them discover their true goals. Which not only helps clients better understand what they are really looking for in life, but also allows the advisor to create a better financial plan and enhance client loyalty!

George Kinder is the developer of Life Planning, a deeper and more intuitive style of financial planning. Part of George Kinder’s famous process involves three questions, commonly known as “the Kinder questions”, that probe deeper into a client’s hopes, dreams, and fears, to help the advisor develop a more complete and powerful financial plan.

To watch George use his Life Planning questions – he emotes, he connects, he has a perfect cadence and uses pauses with impact – his approach is as effective as it is dazzling. But I am not George. And unless George is reading this… you are not George, either. While advisors can’t really ask and respond to George’s questions with clients in the same way that George does, many advisors do use his questions and his process with great impact when working with their own clients.

For advisors who are not Life Planners, this is not meant to serve as instruction for how to be a Life Planner (as becoming a Registered Life Planner involves specific Life Planner training). Instead, analyzing the questions used in Life Planning simply provides a way to understand and harness their power, so that advisors can consider whether the elements of Life Planning questions might help them have more fruitful client discussions of their own.

The Kinder Questions are famous in the world of financial planning – but what is less famous is why. While many advisors may know that the questions promise to result in better client connection, motivation, and understanding, and that they can bring clarity and excitement to a financial plan, the reasons behind why these questions do those things are more elusive.

Understanding why (and how) the questions work (from a psychological perspective), though, may help advisors use questions during client meetings more effectively. Because understanding the outcomes questions are meant to achieve (such as the potential emotion evoked when using them) and knowing what to do with the answers that are given, can help advisors guide their clients to find clarity and excitement with their financial plan, not to mention the lasting connections advisors set out looking for when they ask the questions.

While the Life Planning process involves 3 questions, each question serves a complex and very specific purpose. This post will focus only on the first question exploring the client’s ‘Dream of Freedom’, which helps the advisor establish a close connection with the client by ‘co-creating’ a shared vision of the client’s future goals.

Kinder’s ‘Dream of Freedom’ Question Is A Miracle Question

The ‘dream of freedom’ question is the first question that advisors ask in George Kinder’s Life Planning process. It asks clients to do what its title implies – dream about their future and freedom. The question goes as follows:

I want you to imagine that you are financially secure, that you have enough money to take care of your needs, now and in the future. The question is… how would you live your life? Would you change anything? Let yourself go. Don’t hold back your dreams. Describe a life that is complete, that is richly yours.

The question is open and exploratory. George encourages clients to say or describe anything; nothing is off limits, everything and anything is possible. George uses the question to cultivate the perfect environment for the client to provide more and more insight into their goals and priorities.

In therapy, there is a similar process using a question referred to as the ‘miracle question’. The miracle question is a part of solution-focused therapy – a very structured, future-oriented process of therapeutic intervention with proven results. Solution-focused therapy relies on specific practices, such as using the miracle question and strength-finding exercises, and has been empirically examined for its benefits toward change. Additionally, it has an established relationship with financial planning, as using certain solution-focused therapy practices in financial planning has helped clients that are stuck with reaching their goals get past their obstacles so that they can reach – or at least make more progress towards – their goals.

The miracle question was made famous as a therapeutic technique by psychotherapist Steve de Shazer. According to de Shazer, Milton Erickson, a famous hypnotherapist, called it the ‘crystal ball’ technique because it was used to encourage people to gaze into their perfect futures. The question goes as follows:

Suppose that while you were sleeping tonight and the entire house is quiet, a miracle happens. The miracle is that the problem which brought you here is solved. However, because you’re sleeping, you don’t know that the miracle has happened. So, when you wake up tomorrow morning, what will be different that will tell you a miracle has happened and the problem which bought you here is solved?

The therapist, hypnotist, or financial planner asks the client all about what they see. Who is there? What is different? How have things changed? This approach relies on social constructionism, a theory rooted in sociology and that involves communication, which suggests that reality can be developed collaboratively. Through dialogue and negotiation, the therapist (or financial advisor) and the client socially construct (i.e., work together collaboratively to develop) a shared vision of the client’s miracle life, leaving both the therapist/financial advisor and client with a clear picture of the dream and an understanding of the dream in the client’s life.

While asked in different ways, George Kinder’s Life Planning question and the miracle question share a very clear connection. They both ask clients to dream a dream, and they both use dialogue between the advisor and client to identify the context for the miracle or dream. Essentially, both questions involve more than just the asking of the question; they also rely on a continuing dialogue to ensure that both parties know what the other is ‘seeing’ and understand what is happening. Importantly, they also emphasize why the miracle/dream matters, and what significance it has for both client and advisor.

Trust And Relationship ‘Stickiness’ Result From Socially Constructed Goals

While the idea of a socially constructed goal that the advisor and client uncover, expand, and develop together may sound like a simple idea (and to a certain extent it is), the reality is that the process involved in developing such goals takes time to do. This is not a quick process.

For instance, many advisors understand that clients do not always know what their goals are, or may struggle to articulate the details of their goals. Some clients may tell their advisor that their goal is to retire, but it is very rarely, if ever, about simply not working. Financial advicers know that they often need to give clients time, space, and guidance to describe their goals. They do this by patiently helping the client to dig deeper, and persistently encouraging them to keep digging.

This is where the dialogue involved in creating the socially constructed goal becomes so important. By using dialogue and engaging in the process of developing a socially constructed goal, the advisor may also uncover that retirement for their client really means more time with grandkids. And understanding that the client’s retirement means more time with grandkids gives the advisor more insight into how the client envisions retirement, it also provides more options for the advisor to discuss with the client.

For example, a client who wants to spend more time with their grandkids in retirement may be able to find ways to spend more time with grandkids even before retirement. With this awareness from the client sharing the meaning of what retirement looks like for them, the advisor now has flexibility in offering different and potentially unconventional options that will still address the client’s true goal (e.g., perhaps the client can put off retirement and focus on finding ways to start spending more time with their grandchildren).

Importantly, socially constructed goals require a lot of dialogue and a lot of follow-up questions, as the process requires a great deal of thought, planning, practice, and patience on behalf of the advisor. Because even more important than asking the ‘dream of freedom’ question is the ensuing dialogue that results and continues afterward as the advisor works to actively take part in what the client’s goals mean to them. And when it comes to developing trust and relationship stickiness, this extra work to share the client’s goals can be well worth the squeeze.

This is because, as clients naturally get nervous about goals and their ability to reach them all the time, a part of their fear often comes from a lack of a shared, concrete understanding. Clients get nervous when ‘retirement’ is the goal, especially when there is no clear context around what that means for them; how can they trust their financial advisor when they say, “Everything is going to be okay”, when no one – not even the advisor – really knows what “everything” even means?

Conversely, when an advisor explains to the client, “Even with the current market volatility, you can still take your grandkids on that trip”, the client is reassured that the advisor understands exactly what their priorities are, and because of this shared meaning between advisor and client, the client is much better able to trust the client. When goals are socially constructed and there is ample dialogue to understand and explore those goals, there is generally a dramatic reduction in client fear.

The true goal the client has can be effectively addressed, because the client knows that the advisor has an explicit understanding of those goals. Brené Brown discusses this same dynamic in the context of leadership development in her book, Dare To Lead. As, when we co-create goals, everyone knows what ‘done’ looks like, and this shared understanding can be highly reassuring. The leader (or the advisor) doesn’t have to set the goal; instead, the leader facilitates the process to achieve the goal. In doing so, the leader/advisor ensures that they, as well as the client, each agree on the direction to take and what it will look like when they both get there. There is a lot of emotional safety involved in that picture.

The true goal the client has can be effectively addressed, because the client knows that the advisor has an explicit understanding of those goals. Brené Brown discusses this same dynamic in the context of leadership development in her book, Dare To Lead. As, when we co-create goals, everyone knows what ‘done’ looks like, and this shared understanding can be highly reassuring. The leader (or the advisor) doesn’t have to set the goal; instead, the leader facilitates the process to achieve the goal. In doing so, the leader/advisor ensures that they, as well as the client, each agree on the direction to take and what it will look like when they both get there. There is a lot of emotional safety involved in that picture.

The other benefit that comes from socially constructed goals is relationship stickiness. The advisor is a crucial part of the client’s goal-development process. And that is powerful. Any advisor could ask, “When do you want to retire?” and do a projection based on the client’s answers, but this interaction offers little room for relationship stickiness. However, an advisor who knows that the client wants to spend 3 months in Italy each year taking cooking classes because their perfect life involves spending all of their time and money on cooking for their family, in the new kitchen they design, so that they family actually wants to come and sit around the table with them for hours each week – this has staying power.

When dreams are co-constructed between advisor and client, the goals and desired outcomes are something that both parties uniquely and intimately share. When advisors co-construct with clients, no other advisor will do.

How To Spend Time Co-Constructing After Asking The Dream of Freedom Question

As discussed earlier, using George Kinder’s ‘dream of freedom’ question and the ensuing co-construction dialogue can take a lot of time. And, as many advisors may know, clients are not usually prepared for this question. As such, a great first step advisors can take to help their clients dive right in – even before asking the dream of freedom (or miracle) question in person – is to let clients know it is coming.

Preparing Clients For Unexpected Meeting Questions

Before starting the conversation, advisors can prepare the client by sending an email or having a brief conversation in the meeting beforehand with messaging that says something like this:

Hi Carl & Cheryll!

I am really looking forward to our upcoming Discovery meeting. The purpose of this meeting will be to develop a shared understanding and insight into what your dreams are and where your fulfillment comes from. What comes out of this meeting will directly inform the development of your financial plan and the many future iterations of it to come.

I am sharing the questions you will be asked in advance. Please take the time to look over these independently as well as together. I also encourage you to jot your thoughts down, over the next few days, as you ruminate on these questions before our meeting, whatever comes to mind.

- Imagine you are financially secure and that there is enough money to take care of your needs, now and in the future. How would you live your life?

- Imagine you visit the doctor who tells you that you only have 5 to 10 years left. You will remain as healthy as you are today and you won’t feel sick, but your time is restricted. What will you do in the time you have remaining to live?

- Finally, imagine your doctor says you have one day left. Notice what feelings arise as you confront your very real mortality. Ask yourself: What did I miss? Who did I not get to be? What did I not get to do?

I look forward to the opportunity to learn more. Please let me know if there are any questions.

Sincerely,

Penny Planner

In the message above, Penny Planner has laid some important groundwork for the client. In particular, Penny has not only explained what they are going to discuss (the questions are listed), but she has also told them why it matters (answers from this exercise will be used to develop the financial plan).

This is important, because clients generally won’t expect this line of deeply personal questioning and may not know how to answer these questions right away. And if clients aren’t prepared for these questions, along with the ensuing dialogue that comes with them, the questions may fall flat because clients may be resistant to buy into the process without at least some advance warning. Sending a simple email in advance can help prepare the client and allows the advisor to jump right in, in the next meeting.

So telling clients in advance, and asking them to write their ideas down, can help them adjust to the idea and make it easier for the advisor to start the conversation when the time comes. Furthermore, briefly explaining (in just a sentence or two) the ‘why’ behind these questions can help to bring any initial walls down by helping the client understand the advisor’s intention, which is a powerful way to develop trust.

In traditional Life Planning, Registered Life Planners are advised not to tell clients about the questions ahead of time, as they can create a sort of ‘shock-value’ that a trained Life Planner can potentially use to elicit and facilitate organically spontaneous discussions. However, for advisors who are not trained as Registered Life Planners, telling clients ahead of time can help both the advisor and client be more comfortable with the discussion and potentially mitigate any awkwardness around the unexpected and unconventional line of questioning.

Initiating The ‘Dream-Of-Freedom’ Discussion

When Penny finally meets with her clients, Carl and Cheryll, she knows they will not be surprised by the questions she is going to ask. When she first asks the question, reiterating the importance and reason can be helpful to set the stage. The meeting proceeds as follows:

Penny: Hello Carl and Cheryll! I’m so glad you’re both here. We are going to start by walking through the questions that I emailed to you earlier this week, which I think will provide us with valuable information to help us consider how we should develop your financial plan.

Cheryll: Yep, I made some notes. Thank you for warning us a bit, those questions were tough.

Carl: Yeah, I wasn’t expecting those types of questions.

Penny: [smiling] Yes, so let’s jump right in. Cheryll, as you have your notes, tell me – you are financially secure, you have enough money to take care of your needs now and in the future. My question is, how would you live your life? Would you change anything? Let yourself go. Don’t hold back at all. Describe for us a life that is complete, that is richly yours.

Cheryll: I thought a lot about this, and I decided that I would be volunteering a lot more through my church. I also want to spend more time with my grandchildren.

Penny: Tell me, what type of volunteer work would you do through your church? Describe for me what that would look like, who would be there, and what the cause would be?

Cheryll: Ha. I just knew you would ask a follow-up question that I hadn’t fully fleshed out.

Penny: Take your time. I’m going to be asking a lot of follow-up questions today, because I want to ensure that I can share your vision. There is no rush. And there is no perfect answer.

Cheryll: Well….

Cheryll and Penny continue their dialogue, going back and forth as they uncover and expand on Cheryll’s dream. Even though the conversation between Cheryll and Penny feels light, Penny continually encourages Cheryll to take her time as a way to alleviate any pressure and to normalize the discussion; it is a new approach and, even though it can be hard, it’s what they are here to do and it’s okay to take it slowly.

Penny and Cheryll will continue until it feels like they have reached a natural conclusion. If there is any uncertainty about when to conclude the discussion, a good framework to (loosely) follow would be to ask 3-follow-up questions and offer 2 summary statements for each point of discussion.

For example, in the dialogue below, Penny asks 3 follow-up questions to follow up about Cheryll’s interest in volunteering, then summarizes what she learns. She will follow up with more questions and another summary.

Penny: [asking follow-up question #1] Describe volunteering in more detail for me. Is this time, is it money, it is both?

Cheryll: I’d like to commit some of my time to the church. I already tithe, and I could spend more, but what I am describing when I say volunteering is my time.

Penny: [asking follow-up question #2] Awesome, what are you doing during this time when you’re volunteering? Are there current opportunities at your church or do you want to start your own movements?

Cheryll: Hmm. Well, there is a young mothers’/women’s ministry. I have been interested in getting involved with them, but I am not really sure.

Penny: [asking follow-up question #3] And what is it about the women’s ministry that is most interesting to you?

Cheryll: I am interested, I think, because I relate to the other women in the group. I haven’t really thought about it beyond that, it just seemed like a natural thing.

Penny: [summarizing what she’s learned about Cheryll’s volunteering dreams] Cheryll, this is great. Let me repeat back to you some things that I have heard. Volunteering means time and you want to spend that time doing ministry with other women in your church. Is that right?

Cheryll: Yes, that is right. And, well, actually hearing that out loud, I’m not really sure it’s so much about the ministry. I mean, the ministry is great, but I think I want to be involved through the church working on women’s initiatives. For example, there’s a job readiness program and a daycare center. I would want to volunteer at the daycare and set up clothing drives for women through the job readiness program.

Penny: Oh my gosh, yes. That is so different than what I had envisioned. I am so excited about this idea!

Cheryll: Yeah, me too! I really didn’t put it all together until now.

Penny: [asking follow-up question on new information learned] Okay, well, let me ask you a few more questions. When you envision yourself volunteering at the daycare, what are the hours? Can you just come and go? Would you teach?

Cheryll: I’m not really sure. Those are all great questions. I will have to think about them and find out.

Penny: [another follow up] Yes, please let me know what you find out, and then we can add more to clarify your goals as we go along. Now tell me about how you envision the clothing drive.

Cheryll: I think this one comes to me just because I have so many work clothes that I won’t need anymore once I retire. I would imagine others do, too, and I’d want them to go to women that can use them.

Penny: [again, summarizing new info just learned] This is really great! I might have some clothes too that I could donate. Okay, so let me summarize again what we just went over. You will find out more about the daycare, and in the meantime, you want to focus on women’s career initiatives. Is that a fair way to describe your interests?

Even though Carl didn’t participate in the example conversations above, it is worthwhile to note that it is totally fine (and even encouraged, if clients are comfortable) for the second spouse or partner to interject and make comments during the dialogue with the first partner, as the clients are learning about one another and potentially co-creating together as well. This is commonly how dialogues go with married clients, and they can be a positive and healthy part of the process.

Furthermore, it is very likely that how the first partner of a couple responds to the advisor’s questions may influence the second, but this is why an advicer would send the email encouraging the clients to think about and record their ideas in advance. Essentially, it is fine for one client to influence the other (assuming that each client gets a chance to talk), but asking them to note a few things before the meeting also helps to ensure that each individual gets to provide their own unique viewpoints.

For advisors who are not precisely sure how to frame a follow-up question, or when they just don’t want to say, “Tell me more” yet again, follow-up prompts similar to those used with the Miracle Question, such as the ones listed below, can help to keep the conversation flowing. These questions can help advisors guide the client to explore the differences between their dream goals and their reality today:

- Now that you have described your dream, tell me what things are different about that situation compared to your life right now.

- Who else is there with you? Describe the scene for me.

- Tell me, how do you think others would feel or think about this perfect future? And what do you observe about these people that leads you to believe that they feel that way?

- Have there been times in your life when you have experienced some part of your dream? What happened?

- Tell me more about how you are feeling in this moment, not just what you are doing?

- Share the motivations behind the behavior or experience?

While this article describes how advisors can use George Kinder’s Life Planning questions (along with the miracle question), actually going through the Kinder training, or at least getting started with just one of the core training courses, will provide hands-on training, real-time feedback, and practice so that asking these questions, and learning to respond to them, will become second nature.

After Penny has learned about Cheryll, she can turn to Carl. Penny might ask the exact same question in the exact same way, but it is worth pointing out that there are other ways to ask the questions and explore the same areas with Carl. The following are a few other ways to ask a miracle question:

- What would you do if you knew you would be able to achieve it without failing?

- Imagine a time in the future when you have no more worries. All present barriers are gone. What would be different that would tell you that this positive future has arrived?

- Assuming all things are possible, what would be different about how you imagine you would behave?

Advisors can choose to ask the miracle question, or any variation of the questions presented above with either spouse. They are all slightly different flavors of the same underlying goal – to get clients to dream without limitations. While not all advisors may want to become Registered Life Planners, many may still benefit from asking their clients to dream larger dreams. Having different ways to hold the conversation can help advisors choose what works best for them and still harness the benefits of the Kinder question process. It is also okay to use the Kinder question exactly with both members of the couple in the same meeting.

Having a variety of questions that essentially ask the same thing can also help clients who may get stuck on the question the first time they are asked. These variations on a theme can be a way to help them think about their goals from slightly different perspectives. If you asked one partner the question one way, you could ask the other partner another way. Furthermore, different iterations using any combination of these questions may bring out different answers for people; the point here is just to have options so that, as unique individuals themselves, advisors can find what feels most natural to them.

When Penny resumes her conversation with Carl, it starts like this:

Penny: Carl, now it’s your turn. Tell me, what would you do if money were no object, and you knew you wouldn’t fail?

Carl: I would go to Italy and learn to cook.

Penny: Italy and cooking, okay. Who are you going to cook for? Tell me, what is the motivation behind learning to cook?

Carl: I was prepared for that question…

After Carl and Cheryll have both had time to share, Penny allows the couple some time to reflect before she starts the critical step of summarizing what they have all co-created together. While this may sound simple, summarizing is just as important as asking the follow-up questions, as this is how the advisor orally documents the shared dream that has been co-created.

Penny: Thank you both for being so open and willing to share with me. I have so many notes. If you don’t mind, I want to summarize a few things again just to ensure we have a shared understanding between us. Please correct me if I have any of this wrong.

Cheryll & Carl: [nearly in unison] Shoot…

Penny: Cheryll, I am taking from you said that you want to volunteer in your church with a particular interest in working with young children and helping women with career readiness. You envision spending two days each week doing this, as last summer you spent about two days a week volunteering and found that fulfilling. As it pertains to your kids and grandkids, each year you want to plan for at least one big get-together; next year you want to take the whole family to Colorado and do the Polar Express Train.

Carl: I vote for that train ride, too. It is pretty cool.

Penny: [smiling at Carl and Cheryll] Did I miss anything, Cheryll?

Cheryll: No, I think that works!

Penny: Carl, you, too, want time with your grandkids, but you described them in your home… eating food that you want to learn to cook while in Italy. So, for you, I am hearing that you want personal enrichment through cooking classes. I am also hearing that traveling is important to you, as you didn’t say cooking classes in the United States, but specifically mentioned Italy. You also want to either move to a home with a better kitchen, or ensure that you have the funds to redesign your current kitchen to have more space. Did I get all that right?

Carl: Mostly, but there was no mention of Cheryll in what you said. I do want to cook for my kids once a week, but I also want to travel with Cheryll and cook for Cheryll every night. If we are going to slow down, I want to place an emphasis on being with her.

Cheryll: [emotionally smiling at Carl] I love you, too, Carl.

Penny: Okay. I love it. We will amend my notes to say Carl wants to spend time with grandkids and Cheryll, eating, traveling, and enjoying the slower comforts of life together.

Carl: Perfect!

Penny: Great. Now that we have agreed on our shared vision, I want to do one more thing to connect this directly to your plan. Before we move on to the next question, I would like to ask each of you to share, in one or two sentences, how you would summarize your dream of freedom? I’m not asking so much about behaviors; I want to know more about the feelings, emotions, values, or morals you associate with your dream.

Carl: Easy. For me, it’s having more mindfulness. I want to place a higher priority on being present.

Cheryll: Hmm… I guess for me it would be more connection? Experience? I think my dream of freedom is to use my experiences as a bridge to building deeper connections with others.

Penny: Wow, these are wonderful. We will come back to these points and many others as we work through your plan – we’ll use these statements as guideposts as we work through the decisions you need to make about how you’d like to use your time and resources.

And so Penny completes the meeting, ensuring that the discussion around George Kinder’s first Life Planning question circled back to creating her client’s plan. By asking good follow-up questions, she not only understands her client’s vision, but she has also helped them co-create it. Carl and Cheryll are now connected to Penny through these discussions, and Penny is connected to them – there is trust, understanding, and clarity for everyone involved, including a glimpse into the potential freedom and joy that the planning process can bring.