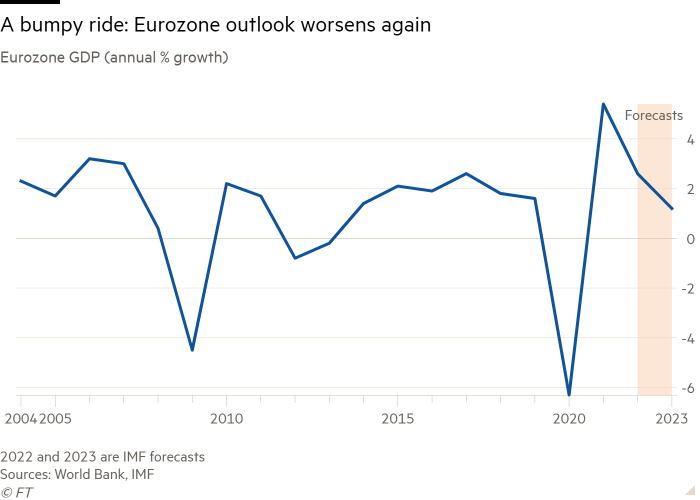

The eurozone is forecast to eke out growth fractionally above zero in the second quarter, but economists expect a steady deterioration in the bloc’s economy over the next year as recession risks loom.

Eurostat’s first estimate of second-quarter gross domestic product, out on Friday, is expected to show an expansion of 0.1 per cent from the previous quarter, according to a poll by Reuters. That marks a sharp deterioration from 0.6 per cent growth over the previous three months and would be the weakest performance since a surge in coronavirus infections and restrictions dragged the bloc into a short recession at the start of 2021.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February has sent energy and food prices soaring, eroding the spending power of consumers while threatening to unleash an energy crisis that leaves manufacturers and households short of gas over the coming winter. Political instability in Italy ahead of elections in September adds to concerns about the bloc’s outlook.

“It is like watching a car crash in the making, a slow-burn crisis,” said Katharina Utermöhl, senior European economist at German insurer Allianz. “Unlike in the pandemic, there is unlikely to be a marked rebound next year.”

One bright spot is tourism and hospitality. The eurozone economy is likely to get a boost from more people taking advantage of reduced coronavirus restrictions to go on holiday or eat out in restaurants this summer, as they spend some of the extra money they saved during the pandemic.

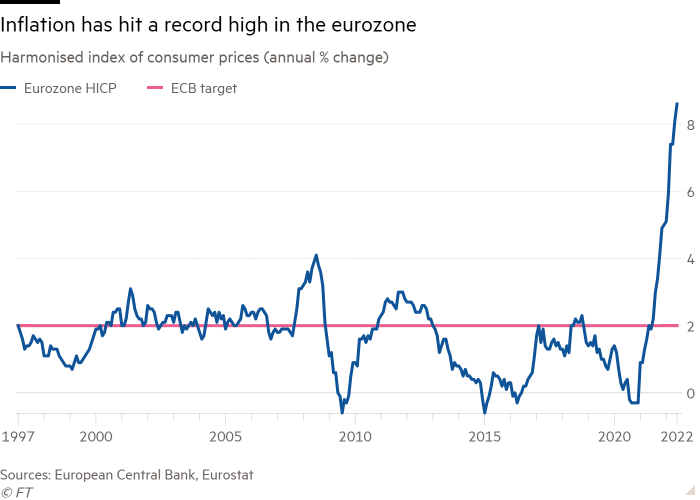

But this boost is likely to be muffled by growing household anxiety over the higher cost of living. Most eurozone consumers are feeling the pinch because their pay has not kept pace with inflation, now at a record high of 8.6 per cent, leaving them worse off.

“We are only forecasting a small boost to growth from tourism, travel and accommodation this summer as the real income squeeze gains pace, dampening consumers’ discretionary spending,” said Veronika Roharova, head of developed Europe economics at Credit Suisse.

Russian energy group Gazprom said this week that flows through its main Nord Stream 1 pipeline to Germany have been halved to about one-fifth of their normal levels from Wednesday due to maintenance, intensifying concerns that Moscow is weaponising energy supplies to Europe. European gas prices jumped 30 per cent in the first two days of this week. They have risen nine-fold in the past year.

A prolonged reduction in Russian gas flows to Europe could leave the region unable to fill its storage facilities sufficiently before this winter’s heating season, forcing supplies to be rationed for heavy industrial users.

A complete cessation of flows “could force energy rationing, affecting major industrial sectors, and sharply reduce growth in the euro area in 2022 and 2023”, the IMF warned on Tuesday as it slashed its forecast for German growth next year by 1.9 percentage points to 0.8 per cent, the biggest downgrade of any country. Without a shut-off, the fund expects the eurozone to grow by 2.6 per cent this year and 1.2 per cent next year.

The EU has set a target for most countries to cut gas usage by 15 per cent. The German government this week urged households and companies to save even more and Berlin plans to let energy companies pass on 90 per cent of their higher costs to customers. “We are in a serious situation,” said Robert Habeck, Germany’s economy minister. “It’s about time that everyone understood that.”

Government measures to cut fuel, electricity and public transport prices are likely to have kept a lid on inflation. But consumer prices are still expected to have risen to a new eurozone record of 8.7 per cent in July in Eurostat figures published on Friday.

Higher prices have been blamed for a string of gloomy economic data. These include the first fall in eurozone business activity for 17 months, as indicated by S&P Global’s latest survey of purchasing managers, and the drop in German business confidence to a two-year low, as measured by the Ifo think-tank’s monthly survey.

Meanwhile, consumer confidence fell to a record low this month, according to the European Commission’s monthly survey.

Banks are also squeezing the supply of loans to eurozone households and businesses — a trend that is likely to accelerate after the European Central Bank raised interest rates for the first time in over a decade last week.

The worsening outlook has already prompted investors to bet the ECB will stop raising rates much earlier than they expected only a few months ago.

Germany’s 10-year bond yield — a benchmark for eurozone interest rates — on Tuesday dropped below 1 per cent for the first time since May after falling from last month’s eight-year peak of 1.77 per cent.

“The window of opportunity for the ECB to keep raising rates is closing as the economy is weakening,” said Spyros Andreopoulos, senior European economist at French bank BNP Paribas.

The nightmare scenario for the ECB and governments alike would be stagflation, with an interruption to Russian gas supplies sending the eurozone into recession while the energy crisis and a weaker euro continue driving prices even higher.

On Wednesday, Goldman Sachs downgraded its forecast for the region, saying a technical recession of two straight quarters of negative growth this year was now more likely to happen than not, even if Russia did not completely cut off energy supplies. A sharper downturn was likely “in the event of an even more severe disruption of gas flows, a renewed period of sovereign stress or a US recession”.

Credit Suisse’s Roharova predicted eurozone GDP would fall between 1 and 2 per cent next year if Russian gas was cut off, while inflation would remain well above the ECB’s 2 per cent target for at least another year. “It is possible that inflation remains elevated or falls only gradually even as growth weakens,” she said.