New Jersey has announced a third round of subsidies for consumers, meant to entice them into purchasing electric cars, despite the program’s running out of funding twice in the past two years. Ostensibly, this policy is designed to reduce carbon emissions by removing gas-powered vehicles from the road, an idea pioneered in California (of course), which is gaining momentum at the national level. Soon, it is hoped, average Americans will flood the freeways with Teslas!

Although ostensibly based in the good intentions of saving consumers money while protecting the planet, these subsidy programs have the aura of woke paternalism. Our leaders cry out, “If the masses don’t like the price of gas, let them drive electric!” Unfortunately for the peasantry, the average price of a fully electric vehicle (e-car) is roughly $20,000 more expensive than the typical sedan. Oh, and let’s not forget the cost of installing a charging station, (approximately $1300 to $2700) in one’s garage. Although there is still debate as to the long-run cost savings of an e-vehicle, the up-front cost alone makes it difficult for the average middle-class consumer to afford, especially in an economy with high inflation for most other goods. For that reason, a subsidy program sounds like a good deal for consumers who are on the fence about purchasing a Tesla. (While hybrid cars would also help reduce emissions, the New Jersey program applies to only fully electric vehicles.)

But wait! These subsidy programs may not even save consumers the amount intended in real terms. Much of the supposed savings will be transferred to sellers. The logic behind how this works is remarkably similar to why the price of college tuition continues to rise alongside efforts to make it cheaper through financial aid.

Understanding how e-car subsidies (and college financial aid) is transferred to the seller simply requires a little bit of knowledge of supply and demand.

The Economics of Subsidies.

Government subsidies to consumers always makes for good politics. After all, who doesn’t want to get some money back from Uncle Sam or his nephew in New Jersey? Yes, those subsidies come from taxes, but if I’m specifically targeted for a payback, and if politicians promise to “soak the rich” or pass it on to future generations, grabbing a subsidy might be a great way to save some money. Unfortunately, the direct recipient of the subsidy doesn’t always benefit.

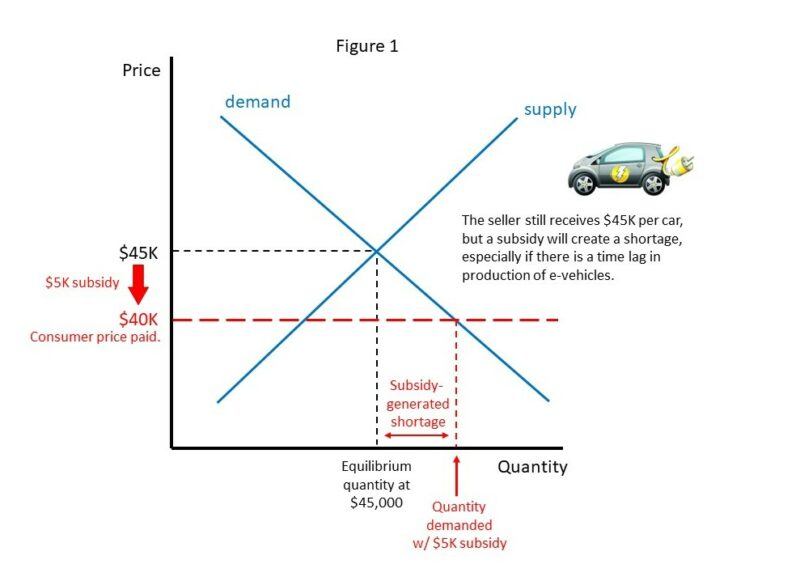

To illustrate, and to make the math easy, let us assume that the price of an average electric vehicle is $45,000. In a free market, this price is determined by supply and demand, with car companies setting the equilibrium price and quantity based on their manufacturing costs and consumer demand. So far, so good. This is standard Econ 101.

If a subsidy of $5,000 per car is offered to consumers, their effective price drops to $40,000 (see Figure 1). Not surprisingly, demand increases. Those individuals who previously had a maximum price of $40,000 at which they were willing to buy an e-car will now head down to their dealer with a government check for five grand in hand. On the supply side, auto sellers still receive $45,000.

But remember, prior to the subsidy program there were still individuals who were willing to buy the car for more than $40,000. All those individuals will have the gains from trade shifted in their favor. The person who was planning to buy an e-vehicle at $45,000 can now get it at $40,000, capturing $5,000 in consumer surplus.

Alas, if the auto company cannot manufacture cars quickly enough to satisfy the rush of new buyers who would be willing to spend $40,000, a shortage will result, representing the difference in the quantity of individuals willing to buy the current supply at $45,000 and $40,000 (see Figure 1). (While a shortage is typically measured by the difference between quantity supplied and demanded at any given price level, remember that the dealer will still receive $45,000 per car while the consumer only pays $40,000, with the remaining $5,000 covered by the government subsidy. That is why Figure 1 shows the shortage between the $45,000 equilibrium price and the quantity demanded at subsidized price of $40,000.)

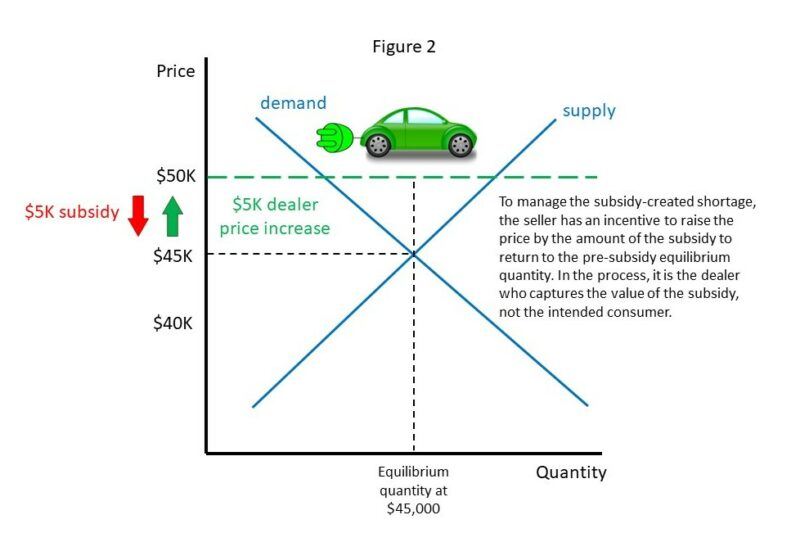

As we also know from Econ 101, the easiest method of allocating scarce goods is to use the price mechanism. Seeing more people wanting the limited number of cars available, the rational response of the dealer is to increase the price of the vehicle back to the point where the quantity demanded meets the quantity of the current inventory. This is easily done by raising the price of e-vehicles by the price of the subsidy (see Figure 2). The car that previously cost $45,000 prior to the subsidy, now sits at $50,000. With the $5,000 government subsidy, though, the real price of the car to the consumer is $45,000. The quantity of buyers at $45,000 remains at the level auto companies were anticipating prior to the subsidy program, and the level at which they set their current inventory. However, sellers now receive an additional $5,000.

Note what happened. People who would have paid $40,000 are once again priced out of the market, and those who would have paid $45,000 still get what they wanted at that price. This is exactly the situation that existed prior to the subsidy with the exception that the sellers, not the consumers, are $5,000 richer. Moreover, there is no increase in the number of cars sold, undermining the policy’s intent of placing more electric vehicles on the roads.

Not So Fast! Bureaucrats Adjust Too.

While I am often reluctant to give government bureaucrats credit, it must be noted that the New Jersey program factored in the behavioral response of sellers. Instead of a simple flat subsidy, New Jersey provided subsidies of $4,000 for autos up to $45,000 and $2,000 for cars from $45-50,000. Vehicles sold over this ceiling would not qualify for a subsidy. This is a politically astute policy in that it appears to be aimed at the middle-class purchaser of the typical e-car, and not the millionaires buying up luxury Teslas.

This two-tiered policy is clever in that car dealers are foiled in any attempt to raise the price of a car from $50,000 to $52,000 to capture the subsidy. Dealers would still have an incentive to raise cars priced below $41,000 to $45,000 to capture the full $4,000 subsidy. And vehicles previously marked from $41-43,000 could also be increased to $45,000, but the dealer would not capture the full $4,000 of the subsidy. And for any vehicle previously priced above $43,000, the dealer has an incentive to raise the vehicle by only $2,000 as that would be the maximum amount of the subsidy that they could collect.

It would appear that the bureaucrats got the better of the car companies. But fear ye not if you are a car dealer. Producer surplus can be captured in ways other than increasing the base price of the vehicle.

Since automobiles are a large purchase that often come with many luxury add-ons, dealers can offer a bevy of different features (e.g., sun roofs, satellite radio) to the base price of the car that allow them to capture the full value of the subsidy. It might be fairly easy to convince somebody who would have purchased a car at the pre-subsidy price of $45,000 to purchase $4,000 worth of special features because, “Hey buddy, you got a ‘free’ four grand to spend courtesy of taxpayers! Let’s SimonizeTM your ride for a great look.” Granted, some of these extras may be of value to the consumer, so buyers still capture some of the surplus, but dealers are also figuring out a way to shift the benefits of the subsidy program in their direction.

The bottom line is that while some consumers may be enticed into buying an electric vehicle sooner than they had anticipated, the real benefit to the consumer are mitigated by price increases and added features that come under the rubric of price discrimination on the part of the seller. Whether this actually does increase the number of e-vehicles that would have been sold under the subsidy program depends on how much dealers are willing to raise prices and offer add-ons to capture the subsidized gains from trade.

Driving College Tuition Prices Upwards.

If the economic logic sounds a bit dubious or confusing, let it be known that it has been playing out in another economic sector: higher education. With a college diploma being deemed an important “public good” that every person should be able to afford, there has been constant pressure to provide financial aid in the form of lower in-state tuition, direct scholarships, tuition grants, and subsidized interest rates on student loans.

As with e-cars, the logic of subsidies plays out the same, but with a more interesting twist.

Universities, surprisingly, do not price their tuition at a market clearing rate, but rather set it below that equilibrium. This comes as a surprise to many parents who think tuition is already too expensive. But think about it. If each university priced their tuition at the market clearing rate, they would have to take everybody that chose to buy it so that they could fill all available seats. Instead, admissions offices prefer a below-equilibrium price so as to intentionally generate more demand than supply. This higher demand allows colleges to pick candidates on criteria other than price – e.g., SAT scores, extracurricular activities, socio-economic status, etc. In other words, generating an artificial shortage with a lower price allows administrators the ability to craft the clientele that they choose. This is particularly true the more elite the college is.

Setting the tuition below the market clearing price generates a line to get in, which in turn generates the annual anxiety of students checking emails to see if they are admitted, wait listed, or rejected. Admissions officers have a very good sense for how long this line needs to be in order to get the demographic and intellectual characteristics desired in its study body. If subsidies are offered to make college cheaper, demand increases and the application line grows longer. But any growth in that line is superfluous in terms of getting the candidate pool needed, and a longer line only adds to the admissions committee’s work.

Therefore, if tuition is made more affordable via subsidies, the rational response of any university is to raise their price in order to shrink the line back to the point where they think the candidate pool is adequate for their purposes. Thus, every time an effort is made to reduce the price of college, university administrations respond with a tuition increase. College becomes more expensive the harder we try to make it less expensive. Oh, the irony!

The proof is in the pudding. If student financial aid is designed to make college more accessible, it isn’t working. Admission rates among the top-tier schools have been holding steady or declining as universities are not expanding their seating capacity at the same rate as growing demand. This pushes much of the demand to lower-tier schools and community colleges. Constrained supply amidst subsidized demand also fuels much dubious behavior as has been witnessed on both the supply (for-profit schools arise to absorb student subsidies) and demand side (e.g., Varsity Blues Scandal).

And just like auto dealers that capture much of the value of an electric vehicle subsidy, the amount of financial aid given to students is funneled directly to the university. Students end up paying the same real amount for college, while school administrations accumulate more revenue to spend on a variety of pet projects.

The Bottom Line

Although subsidies and other forms of government relief to consumers always appeal to voters, the real benefits of such policies are often fleeting to the intended recipients and typically end up helping hidden interests. It is another case of Bootleggers and Baptists. The real beneficiaries may be the politicians who rake in the voter support from specialized interests.

None of this is to say that the goals behind the subsidized policies are bad, a lesson that both Frederic Bastiat and Art Carden have taught us. Electric cars may be a boon to our economy and the environment. And as a professor, I still see the value in a college education (for some, not all folks). Alas, government has been notoriously bad at picking winners and losers. The best “free thing” government could give us is not a bevy of subsidies and handouts, but the freedom to allow entrepreneurs, big and small, to figure out what is best for all of us.