Do you know what a pint of milk costs? It’s a question designed to catch out out-of-touch celebrities and politicians. In these times of inflationary froth, central bankers — and therefore markets — might want to pay attention, too.

Prices for milk, one of the most of basic of commodities, are surging. That matters not only for shoppers, but for those of us after a sign of how sticky inflation will be.

Milk has traditionally proved stubbornly resistant to inflation. Farmers and processors need to keep margins at a minimum if they want to sell their wares to the supermarket behemoths, which are under pressure from discount retailers.

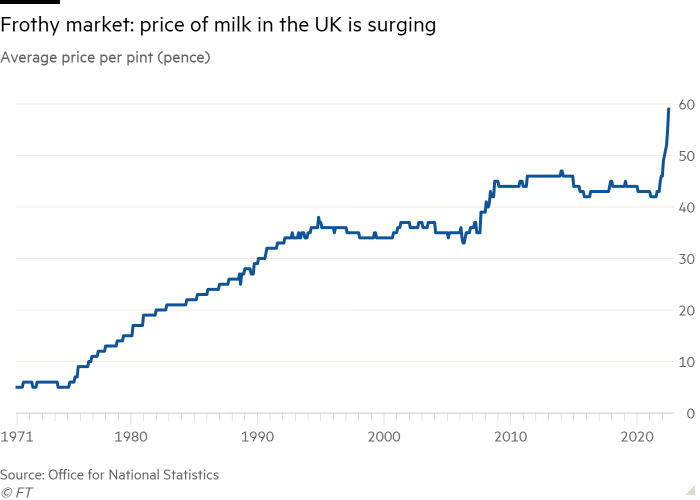

These market dynamics — and the fact that we’re now drinking more dairy-free alternatives — meant that in the UK from 2008 until recently the average price of a pint had been as flat as a glass of the stuff at 42p. Over the past year, however, it’s leapt by 40 per cent to 59p. That might still sound like small change. But for a staple that the average person drinks three of a week, it’s pretty staggering for some.

It’s a similar story elsewhere. In Germany, prices are up by almost a third over the past year, while the cost of a gallon in the US has risen by 15 per cent since January.

So what does the soaring cost of a pint of milk tell us about the nature of inflation? And how much of the recent spurt has its origins in the supply-side shortages that emerged during the pandemic?

That we’re seeing it happen in such a competitive market highlights how embedded price rises have become.

The cost of two of the biggest inputs for dairy farmers — feed and fertiliser — are up 83 per cent and 179 per cent respectively over the past year, according to the UK Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board. “With farm input costs rising so significantly, dairy processors have had to pay more to ensure farmers don’t reduce milk production too much,” says Patty Clayton, the industry body’s lead dairy analyst.

The war in Ukraine has exacerbated supply-side inflation. The media spotlight on Russia’s invasion has also meant the rise in costs has not only been painful, but visible — a crucial factor that has helped processors pass them on to retailers.

Joanna Konings, a senior economist at Dutch bank ING, says the fact that this has happened, after years of tough negotiation with supermarkets, “shows us just how strong the current rises in input prices are”.

Some input prices are now falling, however. Among them is the cost of oil, which is vital throughout the supply chain. “The milk is collected from farms all over the place in tankers so they are using fuel, then processing the milk takes energy as it involves heating it. Then there is the cost of delivering lorry loads of milk and cheese and butter by road,” says Maggie Urry, who used to cover the dairy industry for the Financial Times.

Droughts across the northern hemisphere may have cut short the peak milk-producing “spring flush”, weighing on output. But, with the cost of commodities broadly down in recent months, milk price pressures might have peaked.

I suspect, however, that it will be a while yet before the spillover effects work their way through the supply chain.

When doing their weekly shop, people notice inflation in two ways. The first is if the cost of a staple they buy often goes up. You may or may not know what the price of milk is, but I very much doubt you’d be able to tell whether that bottle of Tabasco sauce you purchase twice a year costs more now than it did during the winter.

The second is if the price of a basket of goods rises. Andrew Porteous, a consumer and retail analyst at HSBC, says: “Everybody has a few items that they know the price of, but what most of us notice is what we pay at the checkout, when we go: ‘Oh my, I’ve spent 55 quid this week rather than 50.’”

Supermarkets — keen not to be outdone by the discounters that have robbed them of market share over the past decade — “want to make sure that the price of their baskets is competitive”, adds Porteous. They do that by tending to raise costs only of products bought occasionally.

Milk is so ubiquitous that even Mark Carney, the former Bank of England governor who was as near to rock star status as central bankers get, knew what the price of half a gallon was. Couple that with an increase in the cost of the average shop and what we have is a very visible rise in inflation.

That visibility matters a lot. It’s likely to not only influence the expectations of shoppers and businesses about where prices will be this time next year, but make demands for higher wages and increases in the cost of other products all the more credible. How can you bemoan paying a farmer more when you’ve felt the pinch yourself?

The rise in the price of a pint looks to me like a portent of inflation’s stickiness. I’d caution against those market bets that monetary policymakers will soon pivot away from increasing borrowing costs. Instead Carney’s successor, Andrew Bailey, and his central banking counterparts elsewhere will have to sit tight while price pressures, from supply chain to supermarket shelf, play out.