“Nobody Knows How Interest Rates Affect Inflation” is a new oped in the Wall Street Journal August 25. (Full version will be posted here Sept 25). It’s a distillation of two recent essays, Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest Rates and Inflation Past, Present, and Future and some recent talks.

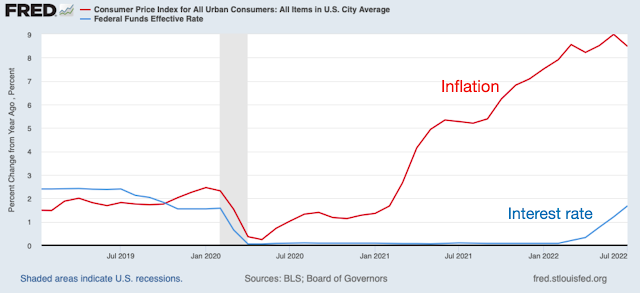

The Fed has only very slowly raised interest rates in response to inflation:

Does the Fed’s slow reaction mean that inflation will spiral away, until the Fed raises interest rates above inflation? The traditional theory says yes. In this theory, inflation is unstable when the Fed follows an interest rate target. Unstable:

In this view, the Fed must promptly raise interest rates above inflation to contain inflation, as the seal must move its nose more than one for one to get back under the ball. Until we get interest rates of 9% and more inflation will spiral upward.

The view comes fundamentally from adaptive expectations. Inflation = expected inflation – (effect of high real interest rates, i.e. interest rate – expected inflation). If expected inflation is last year’s inflation, you can see inflation spirals up until the real interest rate is positive.

But an alternative view says that inflation is fundamentally stable. Stable:

In this view, a shock to inflation will eventually fade away even if the Fed does nothing. The Fed can help by raising interest rates, but it does not have to exceed inflation. (That is, so long as there is no new shock, like another fiscal blowout.) This view comes from rational expectations. That term has a bad connotation. It only means that people think broadly about the future, and are no worse than, say, Fed economists, at forecasting inflation. Story: If you drive looking in the rear view mirror (expected road = past road), you veer off the road, unstable. If you look forward, even badly, (expected road = future road), the car will eventually get back on the road.

Econometric tests aren’t that useful — inflation and interest rates move together in the long run in both views, and jiggle around each other. Episodes are salient. The unstable view points to the 1970s:

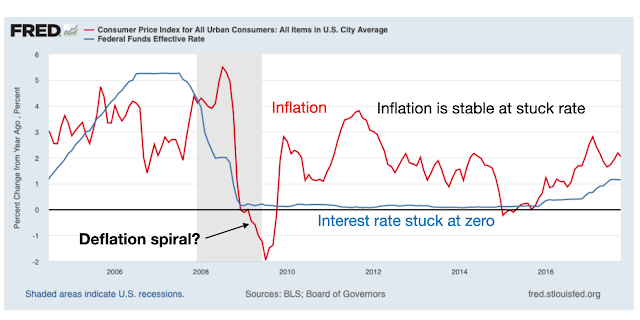

The Fed reacted too slowly to shocks, the story goes, letting inflation spiral up until it finally got its nose under the ball in 1980, driving inflation back down again. But the stable view points to the 2010s:

It’s exactly the opposite situation. Deflation broke out. The Fed could not move interest rates below zero. The classic analysis screamed “here comes the deflation spiral.” It didn’t happen. Wolf. If the deflation spiral did not break out, why will an inflation spiral break out now?

Not elsewhere: As I look at these, I start to have additional doubts about the classic story of the 1970s. The Fed did move interest rates one for one. Inflation did not simply spiral out of control. For example, note in 1975, inflation did come right back down again, even though interest rates never got above inflation. The simple spiral story does not explain why 1975 was briefly successful. Each of the waves of inflation also was sparked by new shocks.

Who is right? I don’t pound my fist on the table, but stability, at least in the long run, is looking more and more likely to me. That says inflation will eventually go away, after the price level has risen enough to inflate away the recent debt blowout, even if the Fed never raises rates above inflation. In any case, it looks like we have another really significant episode all set up, to add to the 1970s and 2010s. If inflation spirals, stability is in trouble. If inflation fades away and interest rates never exceed inflation, the classic view is really in trouble. The ingredients are stirred, the test tube is on the table…

But, that’s a conditional mean. A new shock could send inflation spiraling up again, just as may have happened in the 1970s. New virus, china invades Taiwan, financial crisis, sovereign debt crisis, another fiscal blowout — if the US forgives college debt, why not forgive home loans? Credit cards? — all could send inflation up again, and ruin this beautiful experiment.