There is no plausible way to sugarcoat the impact of an 80 per cent rise in energy bills for UK economic prospects or household finances.

With the energy price cap, which affects 85 per cent of households, rising from an annual average of £1,971 to £3,549 for the October to December period, and further large increases expected in January, the pressure on the new prime minister for comprehensive action is overwhelming.

But economists on Friday warned that any policy response would involve difficult trade-offs. They were also clear that it was impossible to find a government-led solution that was affordable, non-inflationary and well-targeted while also preserving incentives to conserve energy this winter.

“There are big trade-offs and decisions that need to be made but are currently being ignored,” said Torsten Bell, director of the Resolution Foundation think-tank.

The underlying problem for the UK and almost all European countries is that they are net importers of natural gas and, when wholesale prices rise, they become poorer and governments can only distribute the losses. Last year UK net imports of gas accounted for almost 60 per cent of household and industrial gas consumption.

Higher wholesale gas prices — which are currently 15 times normal levels — increase inflation and cut disposable incomes because wages do not fully keep pace with prices.

Alarming inflation forecasts have multiplied since the Bank of England predicted price rises of 13 per cent later this year in its latest quarterly forecasts. This month’s increase in wholesale gas prices has most of the recent forecasts of inflation peaking at 14 to 15 per cent, although Citigroup expects a peak of more than 18 per cent in January.

The differing predictions come down to questions about how much economists expect food prices to rise this autumn and how much they expect the statistical authorities to increase the weight of food, fuel and energy in inflation measures next January.

Whatever the exact peak in inflation, the effect of a higher cost of living not matched by pay increases has already led the BoE to expect the worst squeeze in living standards for the past 60 years and a recession starting this autumn and lasting for more than a year.

Added to this is the difficult economic message that, if all households were simply bailed out, the additional government borrowing and spending would result in even higher inflation because the economy is already operating with no spare capacity.

Even without additional government spending, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research think-tank said that the BoE was now likely to have to deal with a worse inflationary picture in the short term and would have to raise interest rates rapidly to stop a temporary spike in inflation becoming permanent.

“The Monetary Policy Committee will now need to tighten monetary policy faster and by more than we had previously thought. We now expect the policy rate to rise to 4.25 per cent by May of next year,” said Stephen Millard, a deputy director at Niesr.

Whoever wins the Tory leadership race will therefore be playing whack-a-mole with economic policy during the first few weeks in office. Generous universal support will result in greater budgetary costs, inflationary pressure and higher interest rates; more targeted policies will help households less.

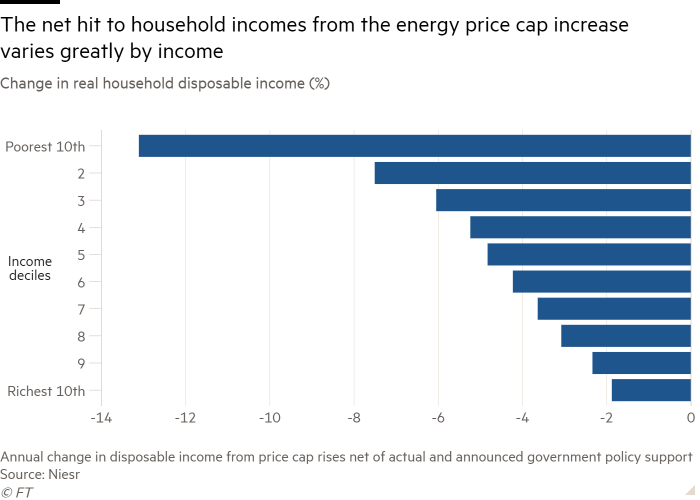

Even with targeted support the pain for households will be extreme, especially among those with low incomes who already devote much more of their budgets to energy than middle-income or richer people.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies, a think-tank, estimates that inflation for the poorest 20 per cent of people will be 17.6 per cent in October compared with 10.9 per cent for the richest fifth.

Niesr predicts that the new price cap will leave real disposable income among the poorest fifth around 10 per cent lower, even after the support already offered.

A further targeted support package is one option available to the new prime minister. The IFS calculated on Friday that the government would need to spend another £14bn to match the generosity of the plan Tory leadership candidate and former chancellor Rishi Sunak put in place in May, when bills were expected to rise only to £2,800.

While Sunak has suggested that this would be close to his preferred option should he become prime minister, Liz Truss, the current frontrunner, has been much more vague. She has suggested a £13bn reversal of April’s national insurance increase, which would mostly help richer households, and a temporary pause on green levies in electricity bills.

Truss has also said she would be inclined not to “bung more money” at the problem but the plans she has announced so far would “have only a modest effect on household bills”, according to Isaac Delestre, an economist at the IFS.

An additional problem, highlighted by the Resolution Foundation, is that energy bills vary greatly between families on similar income levels, so targeting support purely by income would leave some people flush with money and others still lacking funds.

The think-tank said support also needed to “reflect households’ differing levels of energy usage”. According to Bell, the only package that would do this, while keeping costs down and inflation in check would be direct government subsidies to reduce bills alongside higher “solidarity” taxation to fund the costs, something that would probably be an anathema to Truss, the likely new leader of the Conservative party.

“Big bill reductions combined with solidarity taxes, or throwing the kitchen sink at a brand-new social tariff scheme, should be the focus for whoever becomes the next prime minister,” said Bell.

Are you facing difficulties managing your finances as the cost of living rises? Our consumer editor Claer Barrett and finance educator Tiffany ‘The Budgetnista’ Aliche discussed tips on the best ways to save and budget as prices across the globe increase in our latest IG Live. Watch it here.