The factories outside Chennai, in India’s southern state of Tamil Nadu, are home to an array of global corporate names that lend credibility to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Make in India” campaign, which aims to turn Asia’s third-largest economy into a workshop to the world.

The state’s industrial parks host international investors such as Renault-Nissan and Hyundai, which have large car factories; Dell makes computers there and Samsung produces TVs, washing machines and fridges. There are enough suppliers to Apple (including Taiwan’s Foxconn and Pegatron, and the Finnish contract manufacturer Salcomp) that people in Tamil Nadu’s business community commonly refer to the American tech group, which does not discuss its suppliers, as “the fruit company”.

Now India wants to take a step up the manufacturing value chain, with a high-stakes bid to begin making semiconductors. The Modi government has put $10bn of incentives on the table to tempt manufacturers to set up new “fabs” (semiconductor fabrication plants) and encourage investment in related sectors such as display glass. One plant is being planned in Tamil Nadu.

India’s ambition to enter the chipmaking business comes at a time of growing trade and geopolitical tension as western economies have pushed to decouple their supply chains from China, which has invested heavily to become a leader in the semiconductor industry.

The Covid-19 pandemic and Beijing’s draconian lockdowns have disrupted global chip supply and sent companies and governments on a hunt for alternative sources of production. India, which has cracked down on Chinese social media apps and phone producers against the backdrop of a long-running geopolitical dispute, is offering itself as a democratic alternative tech hub to China.

If successful, an Indian chipmaking industry has the potential to be extremely lucrative for the country, feeding rapidly growing global demand as well as its domestic industry’s voracious needs for the computers, appliances and cars it already makes.

“From a geopolitics point of view, India is attractive . . . We are increasingly one of the largest consumers of semiconductors outside of the US and traditional markets,” says Rajeev Chandrasekhar, India’s minister of state for electronics and information technology.

Manufacturers are now lining up to take up the $10bn offer. Singaporean group IGSS Ventures has signed a memorandum of understanding with the Tamil Nadu state government for what its founder and chief executive Raj Kumar says will “very likely” be a wafer factory it wants to build within three years. The Israeli group ISMC, a joint venture between Israel’s Tower Semiconductor and Abu Dhabi-based Next Orbit Ventures, has signed a letter of intent with the state of Karnataka, home of India’s tech capital, Bangalore, to build a $3bn semiconductor chipmaking plant. And Foxconn has teamed up with Indian group Vedanta to build a semiconductor plant, surveying sites in the western Indian states of Gujarat and Maharashtra.

Young Liu, Foxconn’s chair, said on an investor call in August that the group “will be actively expanding” in India. While declining to comment on specific products, he noted “improvements in the overall industry environment in India” adding: “We think India will play a very important role in the future.”

Even given its geopolitical advantages, the road ahead will not be smooth for India as it tries to market itself abroad as an alternative to China. There are risks inherent in the push, not least that Europe, the UK, the US and many other countries are simultaneously laying out billions to subsidise the onshoring of chipmaking, in a move that analysts say is bound to increase global chip capacity. To have any chance of achieving its goal, India will need to move exceptionally quickly and decisively.

‘A whole lot of deficiencies’

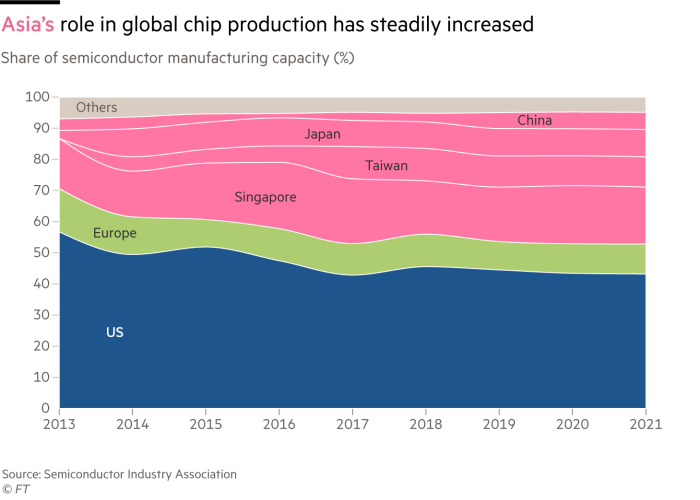

The complexity of semiconductor production and supply chains means that manufacturers in a handful of east Asian countries, led by China, Taiwan and South Korea, have been responsible for much of global supply.

That is now changing. In July, the US passed the Chips and Science Act that includes $52bn of grants to support chipmaking and research and development. Meanwhile the EU is looking to build semiconductor resilience with its own €43bn Chips Act.

While India does not yet make microchips commercially, it does contribute to the design of semiconductors because of its strong software base, says Mahinthan Joseph Mariasingham, a statistician and researcher with the Asian Development Bank.

“When it comes to manufacturing, India has lagged behind many of the other countries, partly because of its lack of facilitating infrastructure,” he says. “It was easy for them to get into the software market because it doesn’t require elaborate physical infrastructure.”

A push into microchip production, which demands some of the most exacting factory conditions of any in manufacturing, would mark a major shift for India. The country has built a reputation as one of the world’s foremost producers (and exporters) of engineering talent, but has struggled to capture a share of top-notch tech manufacturing relative to its 1.4bn population that would come close to that of either China or Vietnam.

Multinationals in lower-tech sectors have long struggled with the country’s at times erratic transport and public utilities. Making silicon chips requires the utmost precision: an interruption in power or water supply lasting just a few seconds can lead to multimillion-dollar losses. Power cuts are common in much of India, prompting many companies to build their own electricity supply.

India’s traditional competitive advantage in low wages will give it little or no edge in the capital-intensive business of making chips. There are also questions about whether the $10bn will be money well spent. India has a tradition, dating back to its post-independence years, of disastrous import substitution policies — measures put in place to protect or promote local industries that instead ended up wasting money and holding back the broader economy.

Some analysts believe India could spend state money better by applying its proven advantages in nurturing skilled IT talent to designing chips for the world to manufacture rather than making its own.

“It’s an attempt to follow the China path and create manufacturing in India,” says Raghuram Rajan, a professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and former governor of the Reserve Bank of India. “But you have to ask why people aren’t manufacturing in India . . . There are a bunch of reasons the government itself accepts: we don’t have the logistics, we don’t have the utilities. Sometimes we don’t have the R&D and the workers . . . There are a whole lot of deficiencies.”

Reviving an industry

If manufacturers in India harbour any doubts about a national foray into chipmaking, they are not voicing them. Instead, the generous central government and local incentives that will defray their initial costs — and a blast of nationalistic, can-do rhetoric from the government — has been welcomed by Indian business.

“This is India’s moment,” wrote Anil Agarwal, chair of the natural resources group Vedanta in a LinkedIn post marking the 75th anniversary of Indian independence in August.

“In the next 25 years, we will build the world’s leading technology hub, even better than Silicon Valley,” claimed the industrialist, who began his career as a Mumbai scrap-metal trader. His subsequent rise through the metals and mining business to sit at the helm of a globally diversified conglomerate is sometimes seen as an exemplar of India’s rise up the business value chain. Vedanta is now set to be one of the country’s first to make chips, in what Agarwal describes as “a beautiful partnership” with Foxconn of Taiwan, the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer.

“Most of the technology work will be done by Foxconn,” says Agarwal. The operation, he adds, will produce both semiconductors and display glass, which Vedanta already makes in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. For its part, Foxconn is giving little information about its plans for the venture, but points out that it has been an early mover in new markets before.

“Foxconn goes to places no one thinks of going at the time,” says Jimmy Huang, acting spokesperson for the company, whose trading name is Hon Hai Technology Group. “Look at our global footprint and consider when we set up shop in each location . . . Today no one believes that India can build up a semiconductor supply chain, but Foxconn is working with the government to set up a semiconductor industry.”

Madhav Kalyan, chief executive of JPMorgan India, says the bank is advising some companies discussing financing operations for chip ventures in India. “They do believe, based on their interactions with the government and this dedicated body, that there is a nuanced understanding of what it takes — and that the government is willing to invest to make it happen,” he says.

New Delhi laid out its pitch to chipmakers last December with the India Semiconductor Mission, unveiled by the IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw. “We have a strategy of broadening and deepening our electronics ecosystem. It’s about laying out the red carpet and bringing in a lot of companies who are seeking to diversify their manufacturing away from being only in China to other places,” says Chandrasekhar.

When Modi came to power in 2014, he says, India had “an almost moribund, nothing electronics industry”, which had been “cannibalised and devastated” by years of free trade agreements. Today, he says, India’s ambition is to more than triple its revenues from the electronics industry to $300bn by 2026, up from $75bn in 2021, and to export $120bn of this amount.

Aside from the central government subsidies, business-friendly states in India’s south and west are vying with one another to capture investments, with tax and other incentives, as well as assurances on land, water, power and other production inputs.

“We give so many incentives, starting with land, the biggest thing in short supply,” says P Thiaga Rajan, Tamil Nadu’s finance minister and a former Standard Chartered and Lehman Brothers banker, who has been active in luring investors to the state. “We have a very proactive policy.”

He points to Tamil Nadu’s past support for investors, including Tata and Foxconn, in building their operations in the state: “We have figured out how to put all the pieces of the puzzle together.”

The lagging edge

Some observers of India’s ambitions to push into semiconductors argue that its heavy emphasis on building up local chip fabrication misses the mark, in a fiercely competitive global industry. They ask how much the industry will have to show for itself when the subsidy money runs out.

“In the semiconductor value chain, there are a lot of steps in the process, and the actual fabrication of chips is only one,” says Christopher Miller, a professor at Tufts University’s Fletcher School and author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, a book about global rivalry in semiconductors. “Many countries that play a big role in the process don’t make chips — and that can still be a lucrative role to play.”

While India might plausibly set up factories making “lagging edge” chips of the kind usable in cars and appliances — which are much in demand in places such as Chennai — it will still struggle to compete against efficient Taiwanese producers or the heavily subsidised Chinese, he says.

Instead of trying to take on longer-established producers in China and elsewhere and setting up “fabs” producing lagging-edge chips made using legacy technology, Miller argues, India might better use its money in chip assembly and packaging facilities, where labour costs are more important. If India were to direct its subsidies into investment in new assembly and packaging facilities, where labour costs are more important, he says, “$10bn could go a long way”.

Rajan, the former central banker, argues that India should be focusing on building human capital rather than chip factories. “Wouldn’t it make more sense to build the software rather than focus on the hardware — and educate 10,000 Indians who can do chip design?” he says.

Rather than trying to direct investment into chip fabrication capabilities, Rajan says, India could channel $100mn into 100 new universities that would train graduates — not just in engineering — and “seed many sectors”. “Even if you were interested in chips alone, training software and design engineers can be the road toward [a major chip designer such as the US’s] Qualcomm, which might be far easier and cheaper”, he says, than imitating a leading manufacturer like Taiwan’s TSMC.

But early investors in the sector echo the government’s view that demand from a growing domestic electronics industry, coupled with the government’s help in defraying producers’ start-up costs, will inevitably support a full value chain, given India’s pool of engineering talent.

Kumar, of IGSS Ventures, who formerly worked for chipmaking giant Global Foundries, points out that Singapore, with a population of less than 6M and where the domestic consumption of semiconductors is “peanuts”, already hosts several wafer fabs.

“Imagine the potential of India,” he says. “For a country that’s going to be a top economic nation, it needs some minimum semiconductor capabilities domestically.”