“Europe will be forged in crisis and will be the sum of the solutions adopted for those crises.” These words from the memoirs of Jean Monnet, one of the architects of European integration, echo today, as Russia closes its main gas pipeline. This is surely now a crisis. Whether Monnet’s optimistic perspective prevails, we do not know. But Vladimir Putin has assaulted the principles on which postwar Europe was built. He simply has to be resisted.

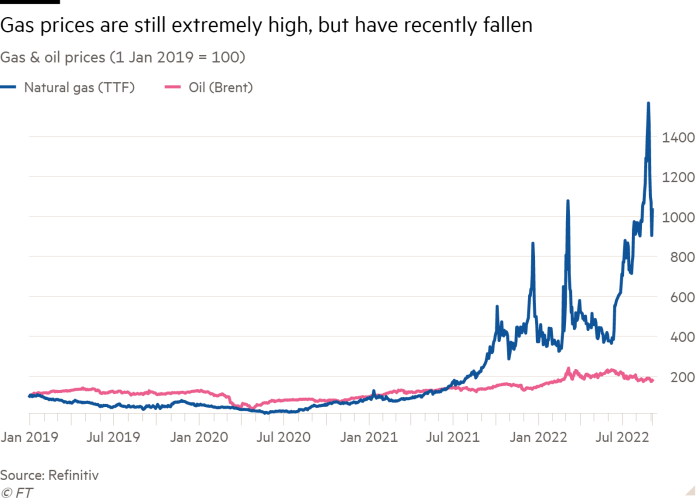

Energy is a vital front in his war. It will be costly to win this battle. Yet Europe can and must free itself from Russia’s chokehold. This is not to underestimate the challenge. Capital Economics argues that at today’s prices the worsening of the terms of trade would amount to as much as 5.3 per cent of Italy’s gross domestic product over a year and 3.3 per cent of Germany’s. These losses are bigger than either of the two oil shocks of the 1970s. Moreover, this ignores the disruption to industrial activity and the impact of soaring energy prices on poorer households.

It is inevitable, too, that sharply rising energy prices will lead to high inflation. The experience of the 1970s indicates that the best response is to keep inflation firmly under control, as the Bundesbank then did, rather than allow desperate attempts to prevent the inevitable reductions in real incomes to turn into a continuing wage-price spiral. Yet this combination of large losses in real incomes with less than fully accommodative monetary policy means that a recession is inevitable.

Difficult though the future looks, there is also hope. As Chris Giles has written: “There is virtually no way to escape a Europe-wide recession, but it need be neither deep nor prolonged.” The likelihood of a recession has probably risen further since then. But work by IMF staff shows that substantial adjustment is feasible, even in the short run. In the long run, Europe can dispense with Russian gas. Putin will lose if Europe can only hold on.

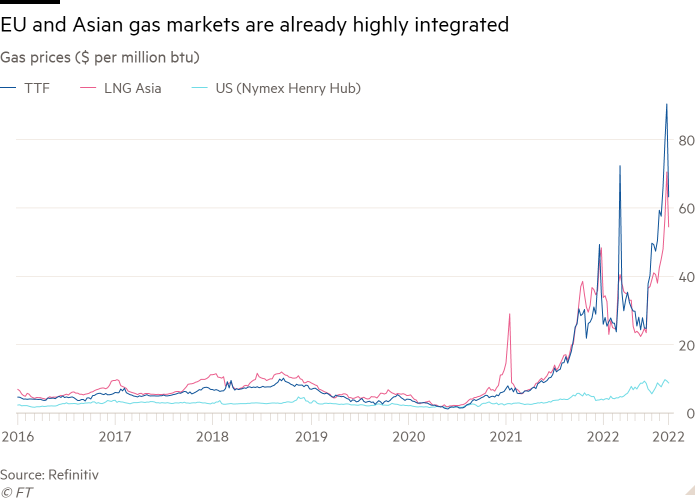

A recent paper from the IMF points to the potential role of the global liquefied natural gas market in cushioning the shock to Europe. European integration within global LNG markets is imperfect, but substantial.

The paper concludes that a Russian shut-off would lead to a decline in EU gross national expenditure of only about 0.4 per cent a year after the shock, once one takes the global LNG market into account. Without the latter, the decline would be between 1.4 and 2.5 per cent. But the former, while far better for Europe, would also mean higher prices elsewhere, especially in Asia. The estimated fall of 0.4 per cent also ignores demand-side effects and assumes full integration of global markets. For these and other reasons, the actual impact will surely be far greater.

Another IMF paper suggests that, with uncertainty added, Germany’s GDP could be 1.5 per cent below baseline in 2022, 2.7 per cent in 2023 and 0.4 per cent in 2024. IMF work on individual EU countries also concludes that Germany would not be the worst hit member state. Italy is still more vulnerable. But the worst hit are going to be Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Czechia.

The big lesson of the oil shocks of the 1970s was that by the mid-1980s there was a global glut. Market forces will surely deliver the same outcome in time. The short-term impact will also be manageable. The needed actions are to cushion the shock on the vulnerable and encourage needed adjustments, which might include emergency reopening of gasfields.

Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission president, has asserted that the aim of policy should now be to reduce peak electricity demand, cap the price on pipeline gas, help vulnerable consumers and businesses with windfall revenue from the energy sector, and assist electricity producers facing liquidity challenges caused by market volatility. All this is sensible, so far as it goes.

A crucial aspect of this crisis is that, like Covid, but unlike the financial crisis, almost all European countries are adversely affected, with Norway the big exception. In this case, above all, Germany is among the most vulnerable. This means that the shock, and so also the response, are in common: it is a shared predicament. But it is also true that individual members not only face challenges that differ in severity, but also possess substantially different fiscal capacity. If the eurozone is to get through this challenge successfully, the question of sharing fiscal resources will again arise. It will ultimately be unsustainable to expect the European Central Bank to be the main fiscal backstop in such a crisis. Yet if weaker countries were to be abandoned, the political consequences would be dire.

At least two further big issues arise. The narrower one is the role of the UK under its new prime minister, Liz Truss. She has an immediate choice: to mend the country’s fences with its European allies in response to the shared threat of Putin, or to break the treaty her predecessor made to “get Brexit done”. Europeans will rightly neither forget nor forgive if she chooses the latter in this hour of need.

The second and far bigger issue is climate change. As Fatih Birol of the International Energy Agency writes, this is not a “clean energy crisis”, but the opposite. We need far more clean energy, both because of climate risks and to reduce reliance on unreliable suppliers of fossil fuels. We learnt this lesson in the 1970s. We are learning it again. The case for an energy revolution has become stronger, not weaker.

How Europe responds to this crisis will shape its immediate and longer-term future. It must resist Putin’s blackmail. It must adjust, co-operate and endure. That is the heart of the matter.