Recent research has linked climate change and socioeconomic inequality (see here, here, and here). But what are the effects of climate change on small businesses, particularly those owned by people of color, which tend to be more resource-constrained and less resilient? In a series of two posts, we use the Federal Reserve’s Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS) to document small businesses’ experiences with natural disasters and how these experiences differ based on the race and ethnicity of business owners. This first post shows that small firms owned by people of color sustain losses from natural disasters at a disproportionately higher rate than other small businesses, and that these losses make up a larger portion of their total revenues. In the second post, we explore the ability of small firms to reopen and to obtain disaster relief funding in the aftermath of climate events.

What Factors Contribute to Disaster Vulnerabilities?

Disaster vulnerability, defined as the susceptibility to severe climate events, is linked to economic, social, and locational factors. For example, people of color and those with low incomes are more likely to reside in high-risk flood zones. And in states like Florida, a growing preference for high elevation is increasing housing prices in areas with lower flood risk that were traditionally inhabited by people of color. To the extent that firms owned by people of color are more likely to be located in communities of color, these trends imply that they may be priced out of areas with lower climate risk.

Disparities in the impact of natural disasters, among those who are exposed to them, are also related to existing inequalities. Practices like “redlining” have continued to keep home values in low-income and predominantly Black areas lower. This may reduce the capacity of communities to finance disaster-resilient infrastructure if, for example, government programs favor areas with higher property values in the allocation of disaster mitigation grants. Indeed, individuals living in formerly redlined districts—many of whom are people of color—remain vulnerable to greater flood risk as compared to non-redlined districts.

Are Small Businesses Owned by People of Color More Likely to Report Disaster-Related Losses?

We use data from the SBCS for the period 2019-21 to document the impact of natural disasters on small businesses. The annual survey provides detailed information on the operations and financial conditions of businesses with fewer than 500 employees and records the demographics of firm owners. Notably, this information allows us to relate climate outcomes to race directly, rather than to the racial profile of geographic areas, as in some existing research.

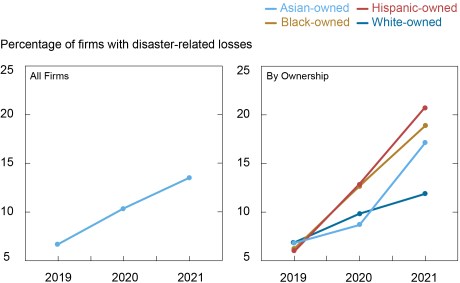

The 2019, 2020, and 2021 surveys included 9,315, 15,234, and 18,190 respondents, respectively. The natural disaster module of the survey asks respondents whether their business sustained any direct or indirect losses from a natural disaster in the past twelve months. The fraction of firms experiencing disaster-related losses rose from 7 percent in 2019 to 14 percent in 2021 (see left panel of the chart below). The racial disparities in these losses increased as well. While there were few disparities in 2019, in 2021, 19 percent of Black-owned firms, 21 percent of Hispanic-owned firms, and 17 percent of Asian-owned firms reported disaster-related losses while only 12 percent of white-owned firms did (see right panel below).

The incidence and racial disparity of losses appear to move together, a pattern that exists even outside our sample period. For example, in 2017 (a year with widespread hurricanes and severe storms), there were large disparities between Hispanic- and white-owned firms in reported losses among SBCS respondents.

Fraction of Firms with Losses and Disparities in Losses Have Both Increased since 2019

Notes: For respondents in each year and race/ethnicity category, the lines show the percentage of firms who answered yes to the question “Within the past 12 months, did your business sustain direct or indirect losses from a natural disaster other than COVID-19 (e.g., hurricane, wildfire, earthquake, etc.)?” A firm is considered Black-, Hispanic-, or Asian-owned if at least 51 percent of its equity stake is held by owners identifying with the group. A firm is defined as white-owned if at least 50 percent of its equity stake is held by non-Hispanic white owners. Race/ethnicity categories are not mutually exclusive. An observation is excluded from the sample if it is missing a response to the question or if the owner’s race is not observed. The sample pools employer and nonemployer firms. Responses by employer and nonemployer firms are weighted separately on a variety of firm characteristics to match the national population of employer and nonemployer firms, respectively. To construct a pooled weight, we use the employer (nonemployer) weight if the firm is an employer (nonemployer).

Among those in disaster-related areas, more firms owned by people of color face damages than white-owned firms. We show this by focusing on the subsample of small businesses located in counties designated as disaster-affected by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in the period of the survey. We find that 24 percent of Black-owned firms, 23 percent of Hispanic-owned firms, and 22 percent of Asian-owned firms reported disaster-related losses in 2021, compared to 17 percent of white-owned firms.

Existing disparities, such as the location of communities of color in low-lying areas with poor disaster-resilient investments, can vary within counties. Using county fixed effects regressions, we find that in 2021, Black-owned small businesses were 5 percentage points more likely than their white-owned counterparts to report disaster-related losses, supporting the disparity in climate effects even within relatively small geographic areas.

Are Business Owners in Some States More Vulnerable to Disaster-Related Losses?

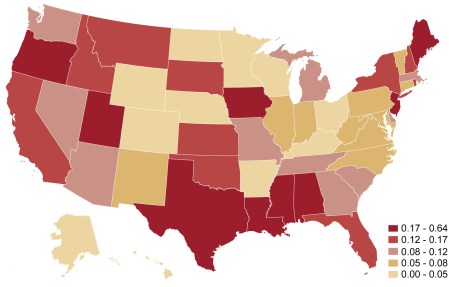

States and cities located in the Southern U.S. are particularly susceptible to disasters, as they have older infrastructure and are disproportionately located in floodplains; as the map below shows, the fraction of firms reporting natural disaster-related losses in 2021 is especially high in states along the Gulf Coast. States in the Middle Atlantic (New Jersey and New York) and on the West Coast also have a high fraction of small businesses reporting disaster-related losses. In 2020 Census data, the states with the highest concentration of African Americans—Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana, and also Washington, D.C.—overlap with these high-risk areas. This suggests that businesses owned by people of color (also concentrated in these four localities, according to the SBCS) may be vulnerable due to their concentration in particularly susceptible states. When looking within Census Divisions, we find that a greater fraction of Black-owned firms report disaster-related losses than white-owned firms, and this disparity has increased between 2019 and 2021. Thus, regional disparities have increased pari passu with national disparities.

Fraction of Firms Reporting Disaster-Related Losses by State, 2021

Notes: The heat map shows the fraction of firms in a given state that answered yes to the question “Within the past 12 months, did your business sustain direct or indirect losses from a natural disaster other than COVID-19 (e.g., hurricane, wildfire, earthquake, etc.)?” All observations that are missing a response to the question are excluded from the sample. The sample pools employer and nonemployer firms. Responses by employer and nonemployer firms are weighted separately on a variety of firm characteristics to match the national population of employer and nonemployer firms, respectively. To construct a pooled weight, we use the employer (nonemployer) weight if the firm is an employer (nonemployer). The survey was fielded September-November 2021.

Do Firms Owned by People of Color Suffer Larger Disaster-Related Losses?

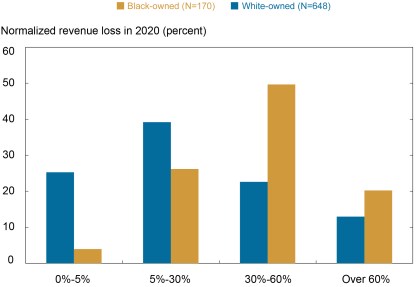

The 2020 and 2021 surveys ask respondents that report disaster-related losses to estimate the value of those losses. We note that, since responses are voluntary (with 78 percent of eligible respondents opting in), firms with lower losses may be less likely to complete the climate-related questions, implying an upward bias in the reported losses. However, there is no reason to think that less-impacted firms owned by people of color are more likely to skip these questions than less-impacted white-owned firms.

We normalize these losses as a percentage of a firm’s total revenue in the year prior. Because people of color faced greater revenue losses as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, we rely on disaster-loss data from the 2020 survey, which is normalized by total revenues from 2019, before the onset of the pandemic.

For most small businesses of color, disaster-related losses were a large share of their revenues. For example, 20 percent of Black-owned businesses reported losses that amount to more than 60 percent of 2019 revenue, while just 4 percent of such firms had losses of 0-5 percent of 2019 revenue (see chart below). In contrast, for most white-owned businesses, disaster-related losses were a relatively small share of revenues. For example, 25 percent of white-owned firms experienced disaster-related losses of 0-5 percent of 2019 revenue and 39 percent had losses of 5-30 percent, while only 13 percent had losses of more than 60 percent of total revenue.

Black-Owned Firms Have Higher Revenue Shares of Disaster-Related Losses

Notes: Among firms that reported disaster-related losses, the 2020 SBCS asks “What is the estimated value of your business’s losses as a result of the natural disaster?” Respondents can select from six categories. Firms are also asked to report their total revenues from 2019 by selecting from eight ranges. To compute the normalized revenue loss, we divide the midpoint of the disaster-related losses range by the midpoint of the firm’s revenue range. The normalized losses are grouped into four bins, which are shown on the x-axis. The bars show the percentage of firms in each race/ethnicity category with normalized disaster-related losses in a given bin. A firm is considered Black-owned if at least 51 percent of its equity stake is held by owners identifying as Black. A firm is defined as white-owned if at least 50 percent of its equity stake is held by non-Hispanic white owners. Race/ethnicity categories are not mutually exclusive. An observation is excluded from the sample if it is missing a response to the question or if owner race is not observed. The sample pools employer and nonemployer firms. Responses by employer and nonemployer firms are weighted separately on a variety of firm characteristics to match the national population of employer and nonemployer firms, respectively. To construct a pooled weight, we use the employer (nonemployer) weight if the firm is an employer (nonemployer). The survey was fielded September-October 2020.

It is important to note that, when we compare disaster-related losses on a dollar basis, rather than as a percentage of revenues, there is little evidence of racial disparities. This suggests that our result is driven by the lower revenues of Black-owned firms, implying that natural disasters are a greater burden for firms owned by people of color through their interaction with existing racial disparities that have a negative effect on small business revenues. For example, relative to white-owned firms, Black-owned businesses are younger, have less access to startup capital, employ fewer people, have a harder time accessing credit, and lack experience in family businesses—all of which are associated with lower revenues.

Looking Ahead

Our findings suggest that small businesses owned by people of color and located in particular geographic areas are especially vulnerable to natural disasters. Moreover, these disparities have increased over the three years in our sample, in tandem with the frequency and severity of disaster events. These disparate outcomes are likely to be closely linked to the broader challenges faced by small businesses of color in accessing credit as well as to underinvestment in climate infrastructure in areas where low-income and high-minority communities live. As such, addressing these challenges may prove especially effective in ameliorating disparities in climate outcomes. In our next post, we examine the resources that small businesses can rely on to cope with losses following disasters, such as access to disaster relief.

Martin Hiti was a summer research intern in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Claire Kramer Mills is a Communication Development Research Manager in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Communications and Outreach Group.

Asani Sarkar is a financial research advisor in Non-Bank Financial Institution Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Martin Hiti, Claire Kramer Mills, and Asani Sarkar, “How Do Natural Disasters Affect U.S. Small Business Owners?,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, September 6, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/09/how-do-natural-disasters-affect-u-s-small-business-owners/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).