The Federal Reserve remits most of its operating profits to the US Treasury. Federal Reserve remittances are government revenues that directly reduce the federal budget deficit. But what is the budgetary impact of Federal Reserve System losses? The Federal Reserve System has not had an operating loss since 1915, so history provides no guidance as to how these losses will impact the official federal government deficit.

In 2023, the Fed will likely report tens of billions of dollars in operating losses as it raises interest rates to combat raging inflation. Will Fed losses increase the budget deficit as logic dictates they should, or will they be treated as an off-budget expenditure? Given the “transparency” of federal budgetary accounting standards, it is not surprising that a recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report suggests Federal Reserve operating losses will be excluded when tallying the official federal budget deficit.

The Federal Reserve earns interest on its portfolio of Treasury and federal government agency securities and receives revenues for the payments system services it provides. Offsetting Fed revenues are the interest the Fed pays on bank reserve balances and reverse repurchase agreements, dividend payments to Fed member banks, contributions (if any) to the Fed surplus account, and the operating expenses of the Board of Governors, the 12 Federal Reserve district banks and their branches. Since 2012, expenses also include the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Any remaining earnings are transferred to the US Treasury and counted as federal government receipts for federal budget purposes.

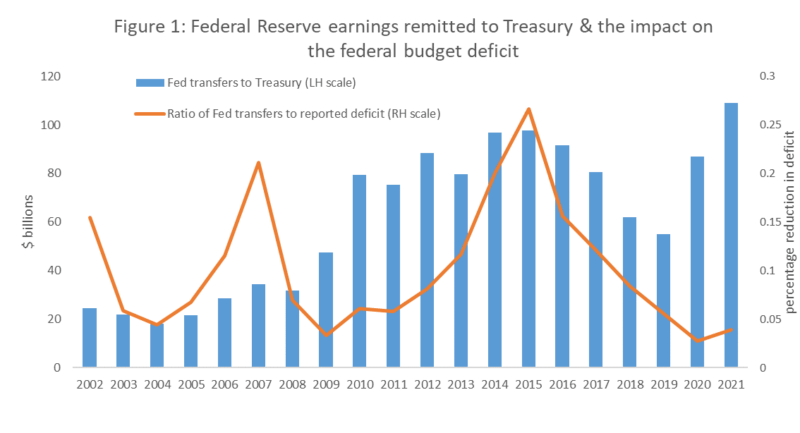

The annual amount of Federal Reserve operating income remitted to the Treasury since 2001 is plotted in Figure 1. Also shown are estimates of the reductions in the reported federal deficits attributable to the remittances. (The Fed reports remittances on a calendar-year basis, while the federal deficit is calculated for a fiscal year ending September 30. The deficit reduction estimates in Figure 1 do not correct for this timing difference.)

In crisis years (2009-2011, 2020-2021) the federal budget deficit is bloated by congressionally appropriated stimulus outlays and reduced tax receipts. In these years, even very large Fed remittances offset only a fraction of the combined federal budget deficit. In years unburdened by massive federal stimulus expenditures, however, Fed remittances offset a substantial portion of the reported deficit.

By the FOMC’s own estimates, short-term policy interest rates will approach 3.5 percent by year-end 2022. As the Fed raises short term interest rates to fight inflation, its interest expense increases. The Fed’s interest expenses and operating expenditures, including about $630 million per year in off-budget funding it is required to provide to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, will soon exceed its revenues.

Our back-of-the envelope estimates suggest that the Federal Reserve will begin reporting net operating losses once short-term interest rates reach 2.7 percent, assuming the Fed has no realized losses from selling its SOMA securities. If short-term rates reach 4 percent, our estimates suggest that annualized operating losses could exceed $62 billion. As discussed below, these loss estimates are consistent with the Fed Board of Governors’ own public estimates.

In 2011, the Federal Reserve announced its official position regarding realized losses on its investment portfolio and system operating losses:

[I]n the unlikely [sic] scenario in which realized losses were sufficiently large enough to result in an overall net income loss for the Reserve Banks, the Federal Reserve would still meet its financial obligations to cover operating expenses. In that case, remittances to the Treasury would be suspended and a deferred asset would be recorded on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet.

Among financial institutions, the Fed has the unique privilege of setting its own accounting standards, and the Fed has decided that, unlike for all its regulated banks, operating losses will not reduce the Federal Reserve’s reported capital and surplus. The Fed will maintain a positive reserve surplus account in the event it books operating losses by offsetting its operational losses, one-for-one, with an imaginary “deferred asset” account, no matter how large the loss. Unless Congress intervenes, the Fed will not remit any revenues to the US Treasury—even as it continues paying dividends to its member banks—as long as this deferred asset account has a positive balance.

Instead of issuing a new marketable Treasury security, which would count towards the deficit, the Fed will cover its losses with a nonmarketable receivable called deferred assets recorded on the Fed’s balance sheet. The economic reality, of course, is that Fed losses increase the government’s deficit.

Federal Reserve Board estimates of the system’s potential cumulative operating losses are mirrored in estimates of its deferred asset balance pictured in Figure 2. The Federal Reserve Board’s own estimates suggest that its cumulative operating losses (in the estimated “90 percent interval” case) could approach $200 billion by 2026, Moreover, the Fed projects that it may not resume making any Treasury remittances until 2030 or later. Keep in mind that these projections assume the Fed can reduce inflation with fairly modest increases in short-term interest rates with the expected short-term rate path peaking at less than 4 percent in 2023, before slowly declining toward 2.5 percent in 2026.

Figure 2: Federal Board of Governors Projection of Treasury Remittances and System Deferred Asset Account Balances 2023-2030

While the Board of Governors fully anticipates operating losses beginning in 2023, the CBO did not get that memo. In its most recent forecast, the CBO projects that the Fed will continue making positive remittances to the Treasury every year between 2022 and 2032. While the CBO forecast anticipates a sharp decline in remittances in 2023 through 2025, it expects a recovery toward 2021 remittance levels thereafter, with the Fed reducing interest rates as inflation returns to targeted levels.

While the CBO does not project any Fed operating losses, its explanation of budget accounting suggests any such losses would be excluded from budget deficit calculations: “Although it remits earnings to the Treasury (which are recorded as revenues in the federal budget), the Federal Reserve’s receipts and expenditures are not included directly in the federal budget…” Operating losses will be a Federal Reserve expenditure, so this CBO statement would appear to exclude Fed operating losses from the federal deficit calculation. It is strange not to count the Fed’s losses in the budget accounting, considering that the Fed’s profits are counted. Perhaps because the CBO does not anticipate Federal Reserve losses, it has failed to consider them explicitly in its description of deficit accounting.

Simple accounting logic suggests that if the federal budget deficit is reduced when the Fed earns revenues in excess of expenses and remits these profits to the US Treasury, Fed losses should increase the reported federal budget deficit. This is especially true since Federal Reserve System losses now include the hundreds of millions of dollars of off-budget funding it is required to transfer to run the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. If the current accounting rules remain unchallenged, the Congress could pass new legislation requiring the Federal Reserve to fund any number of activities off-budget without any impact on the reported federal budget deficit.