This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 345 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year,, and our current goal, supporting the commentariat.

Yves here. What is surprising about this story is how bad the Army is at using social media. Former CIA member Larry Johnson reports that he was directly involved in planting stories that were very much information operations, and often with publications that would be the last to consider themselves CIA stooges.

The other part that is amusing is the tacit assumption that Russia is a genius at this game. If native Americans can’t pull this off in their own country, where they know the musics, the movies, the sports figures, the celebrities, the memes, how is it credible that Russia could be so much more effective?

By John Helmer who has been the longest continuously serving foreign correspondent in Russia, and the only western journalist to have directed his own bureau independent of single national or commercial ties. Helmer has also been a professor of political science, and advisor to government heads in Greece, the United States, and Asia. Originally published at Dances with Bears

The US Army’s Special Operations Command (SOCOM) has been firing several hundred million dollars’ worth of cyber warheads at Russian targets from its headquarters at MacDill Airforce Base in Florida. They have all been duds.

The weapons, the source, and their failure to strike effectively have been exposed in a new report, published on August 24, by the Cyber Policy Center of the Stanford Internet Observatory. The title of the 54-page study is “Unheard Voice: Evaluating Five Years of Pro-Western Covert Influence Operations”.

“We believe”, the report concludes, “this activity represents the most extensive case of covert pro-Western IO [influence operations] on social media to be reviewed and analyzed by open-source researchers to date… the data also shows the limitations of using inauthentic tactics to generate engagement and build influence online. The vast majority of posts and tweets we reviewed received no more than a handful of likes or retweets, and only 19% of the covert assets we identified had more than 1,000 followers. The average tweet received 0.49 likes and 0.02 retweets.”

“Tellingly,” according to the Stanford report, “the two most followed assets in the data provided by Twitter were overt accounts that publicly declared a connection to the U.S. military.”

The report comes from a branch of Stanford University, and is funded by the Stanford Law School and the Spogli Institute for Institutional Studies, headed by Michael McFaul (lead image). McFaul, once a US ambassador to Moscow, has been a career advocate of war against Russia. The new report exposes many of McFaul’s allegations to be crude fabrications and propaganda which the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) has been paying contractors to fire at Russia for a decade.

Strangely, there is no mention in the report of the US Army, Pentagon, the Special Operations Command, or its principal cyberwar contractor, the Rendon Group.

It is unclear who paid for the new investigation which was co-authored by Graphika. This is a New York consultancy without an office address, staffed by US, French and British intelligence analysts, and financed in part by the US Senate Intelligence Committee and the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Graphika advertises its Russia war-making credentials in the mainstream and IT media, as well as on its Twitter account.

Notwithstanding, the new report explicitly targets news faking and other information warfare tactics by the US Army forces aimed primarily at audiences in Central Asia, the Middle East, and Afghanistan.

Source: https://stacks.stanford.edu/

“Our joint investigation,” according to the Stanford/Graphika paper, “found an interconnected web of accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and five other social media platforms that used deceptive tactics to promote pro-Western narratives in the Middle East and Central Asia. The platforms’ datasets appear to cover a series of covert campaigns over a period of almost five years… These campaigns consistently advanced narratives promoting the interests of the United States and its allies while opposing countries including Russia, China, and Iran. The accounts heavily criticized Russia in particular for the deaths of innocent civilians and other atrocities its soldiers committed in pursuit of the Kremlin’s ‘imperial ambitions’ following its invasion of Ukraine in February this year. To promote this and other narratives, the accounts sometimes shared news articles from U.S. government-funded media outlets, such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and links to websites sponsored by the U.S. military.”

The evidence obtained for this investigation has come from Twitter over the period, February 2012 to March 2022. Facebook and the related apps, Whatsapp and Instagram, provided data for the five-year period from 2017 to July 2022. “The Twitter dataset provided to Graphika and SIO [Stanford Internet Observatory] covered 299,566 tweets by 146 accounts between March 2012 and February 2022. These accounts divide into two behaviorally distinct activity sets. The first was linked to an overt U.S. government messaging campaign called the Trans-Regional Web Initiative, which has been extensively documented in academic studies, media reports, and federal contracting records. The second comprises a series of covert campaigns of unclear origin. These covert campaigns were also represented in the Meta dataset of 39 Facebook profiles, 16 pages, two groups, and 26 Instagram accounts active from 2017 to July 2022.”

The analysts’ method: “firstly, we conducted a qualitative review of content samples, metadata, and the profile information associated with each account to determine if an asset should be classified as overt or covert. We conducted additional open-source investigation to determine asset classifications when required. We then built a social media network map of the covert Twitter accounts’ followers. This helped us understand the collective audience these assets built and each asset’s relative influence and community. The resulting network map revealed three major groups reflecting specific regions and nations, including Iran, Arabic-speaking Middle East, and Afghanistan. We used these network groupings as a foundation to review further the covert Twitter and Meta assets and assign labels corresponding to their audience. This included a qualitative review of asset behavior, such as the fake personas they employed online, and a quantitative content analysis of the assets’ most-used hashtags, key terms, and web domains…Finally, we analyzed the assets in each group individually and collectively to identify the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) they employed to conduct their campaigns and the narratives they promoted.”

“The Central Asia-focused campaign first created assets on Instagram, Telegram, Twitter, and Odnoklassniki in 2020, before later setting up accounts on Facebook and VK [VKontakte] in 2021. According to domain registration records, a website for the sham media outlet Intergazeta was created in March 2021. Assets still active on Odnoklassniki and VK provide insights into how this cross-platform campaign operated. Fake personas created by the actors were typically linked to one of 10 sham media outlets, which posed as independent news entities covering events in Central Asia. These fake personas posed as individuals living in Europe and Central Asia, were listed as administrators for the sham media outlets, and posted content from the campaign to different social media groups. On Odnoklassniki, for example, the personas regularly posted to groups including Fighters of Kyrgyzstan [БОЙЦЫ КЫРГЫЗСТАНА] and Central Asia News [Новости Central Asia]. On Facebook, a page for the sham media outlet Vostochnaya Pravda claimed to focus on debunking myths and sharing ‘absolute facts’ about Central Asia…. Vostochnaya Pravda and other assets in the campaign typically posted long text blocks about local news events and geopolitics alongside an illustrative picture. Like all posts by the covert Central Asia assets, this content received close to zero engagement…Some of the ‘news’ pages, such as Stengazeta, used engagement-building techniques, including openly calling for interactions from their readers on what they had just read.”

“We witnessed similar behavior from the only active Facebook profile posting original content. Attempts to grow a follower base were evident on Twitter, where the assets repeatedly tweeted at real users, including pro-Ukraine and pro-Russia accounts…We believe the Facebook pages in the group likely acquired followers inauthentically in an attempt to look like real and organic entities, possibly by purchasing fake followers. According to CrowdTangle data, the pages quickly gained up to several thousand followers in their first few weeks. Subsequently, the pages experienced net losses in followers between June and August 2021, possibly as Facebook deleted the accounts of their fake followers…The pages’ likes experienced the same phenomenon.”

“At least one of the group’s personas featured a doctored profile picture using a photo of Puerto Rican actor Valeria Menendez…. We suspect that at least two other fake users in the group used similar techniques, but we could not identify the original photos. Additionally, at least one cross-platform persona used a picture stolen from a dating website.”

“The sham media outlet Intergazeta repeatedly copied news material with and without credit from reputable [sic] Western and pro-Western sources in Russian, such as Meduza.io and the BBC Russian Service. The sham outlet often made minor changes to the copied texts in a likely effort to pass them off as original content. Intergazeta also produced articles in Russian compiled from sections of different English-language sources. Typically, these sections were literal ‘word-to-word’ translations into Russian, as opposed to more advanced semantic translations, resulting in non-native sounding language. In one case, the outlet posted a Russian-language article about Russian disinformation in China that was almost certainly translated from the English-language version of a Ukrainian article published nine days earlier. Intergazeta was not the only asset to translate content from English sources. Facebook pages in the group sometimes posted Russian translations of press releases from the websites of the U.S. embassies in Central Asia. These posts focused on U.S. financial and material support to Central Asian countries. The posts also copied or translated content from U.S.-funded entities, such as Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, and the independent Kazakh news outlet informburo.kz.”

“Three of the groups also showed clear signs of automated or highly coordinated posting activity. According to data provided by Twitter and Meta, assets in the Afghanistan and Central Asia groups typically posted at roughly 15-minute or 30-minute intervals in any given hour. Furthermore, accounts in the Afghanistan, Central Asia, and Middle East groups almost exclusively posted in the first second of any given minute.”

“The coordination was especially clear when assets in the group posted about U.S.-related news or used translated content from official American sources, such as U.S. embassies in Central Asia. In one example, the Vostochnaya Pravda Facebook page posted a word-for-word Russian translation of an Englishlanguage news bulletin from the U.S. embassy in Tajikistan… The post included a link to a Radio Liberty article on the topic, an excerpt of which was then shared by multiple other assets in the group. The assets also sourced content from media outlets linked to the U.S. military, particularly Caravanserai (central.asia-news.com). This outlet is one of three that previously operated as Central News Online (centralasiaonline.com), which named the U.S. Central Command as its sponsor and, before 2016, was part of the U.S. government’s Trans-Regional Web Initiative.”

“The Central Asia group focused on a range of topics: U.S. diplomatic and humanitarian efforts in the region, Russia’s alleged malign influence, Russian military interventions in the Middle East and Africa, and Chinese ‘imperialism’ and treatment of Muslim minorities. Starting in February this year, assets that previously posted about Russian military activities in the Middle East and Africa pivoted towards the war in Ukraine, presenting the conflict as a threat to people in Central Asia. Assets in the group heavily promoted narratives supportive of the U.S. on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, and Telegram. These posts primarily focused on U.S. support for Central Asian countries and their people, presenting Washington as a reliable economic partner that would curb the region’s dependence on Russia. Other posts argued that the U.S. was the main guarantor of Central Asia’s sovereignty against Russia, frequently citing the war in Ukraine as evidence of the Kremlin’s ‘imperial’ ambitions. Interestingly, the assets also promoted U.S. humanitarian efforts, mentioning the United States Agency for International Development 94 times on Twitter and 384 times on Facebook in the respective datasets.”

The Stanford report has traced the fake social media on the US war against Iraq, Syria and Iran to the MacDill base in Tampa, Florida, where both the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and Central Command (CENTCOM) are headquartered. The military units did a poor job of camouflaging themselves or their locations, according to the Stanford-Graphika group.

“Accounts in the Middle East group frequently used fake profile pictures to construct online personas. This is a common tactic in online Influence Operations, and we increasingly see actors leverage GAN-generated faces such as those shown in Figure 49. While at first presenting as photorealistic human faces, GAN-generated images are typically easy to identify due to their consistent central eye alignment, blurred backgrounds, and telltale glitches around the teeth, eyes, and ears.”

“Based on an analysis of shared technical infrastructure, domain registration records, and social media activity, we assess with high confidence that almashareq.com is the latest rebranding of al-shorfa.com, while diyaruna.com is the latest rebranding of mawtani.com and mawtani.al-shorfa.com. Prior to 2016, al-shorfa.com and mawtani.com were part of the U.S. government’s Trans-Regional Web Initiative… Additionally, Dariche News frequently quoted CENTCOM officials and discussed U.S. military activities in the region. We counted at least 50 Dariche News articles that mentioned CENTCOM. For example, a September 2021 article discussed how Bahraini leaders pledged to work with U.S. Naval Forces Central Command to adopt new technologies. A December 2021 article quoted a former CENTCOM commander saying that the Iranian government was starving people to build missiles.”

“Our investigation identified clear signs of coordination and inauthentic behavior [including] sharing identical content across platforms, coordinated posting times, using GAN-generated faces, and creating fake profile pictures. One Facebook page in the group also posed as a person living in Iraq. This page shared the same name and picture as a Twitter account that previously claimed to operate on behalf of the United States Central Command (CENTCOM). The group chiefly promoted narratives seeking to undermine Iran’s influence in the region but also took aim at Russia and Yemen’s Houthi rebels. For example, accounts on Twitter posed as Iraqi activists in order to accuse Iran of threatening Iraq’s water security and flooding the country with crystal meth. Other assets highlighted Houthi-planted landmines killing civilians and promoted allegations that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine would lead to a global food crisis.”

“One of the Facebook pages in the group showed links to a Twitter account that has previously claimed to operate on behalf of CENTCOM. Created on Nov. 1, 2021, the page used the Arabic word for ‘discoverer’ [ فشتكم ] as its name and presented itself as an Iraqi man posting predominantly about the misdeeds of the Iranian government and its influence in Iraq. Notably, Discoverer used a profile picture likely generated using artificial intelligence techniques, such as GANs. An Instagram account and a Facebook profile in the Middle East group used the same image as well. An account in the Twitter dataset also used the Arabic word for “discoverer” as its name and the same fake face as the three Meta assets. The Discoverer Twitter account was created in November 2016 and claimed in its bio to be ‘always in the service of Iraqis and Arabs.’”

“However, archived versions of the Discoverer Twitter account show that prior to May 2021, it used a different picture, listed its location as ‘Florida, USA,’ and publicly identified as an ‘account belonging to the U.S. Central Command’ that ‘aims to uncover issues related to regional security and stability.’ At that time, the account promoted similar anti-Iran narratives related to Iraq and Syria but also posted statements presented as coming from the U.S. embassy in Baghdad.”

The Trans Regional Web Initiative (TRWI) of SOCOM is revealed in the report as the major US cyber-warfare operation behind the social media faking. But the report itself is silent on this source, and on how much money is currently being spent by the US Army on the operation.

Source: https://sam.gov/

For a British academic study of these operations to 2015, read this.

Source: https://www.socom.mil/about

In US media reporting from 2012, the Rendon Group was identified as the lead contractor for the SOCOM disinformation operations at MacDill. “Also advising SOCOM is longtime public affairs and propaganda contractor John Rendon, whose Rendon Group was instrumental in influencing public opinion before the start of the Iraq War. Rendon has two full-time employees working at SOCOM and has visited the command’s headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base 12 times since Feb. 1, said Col. Tim Nye, a SOCOM spokesman.” At that time, it was reported that “In all, Rendon, a marketing expert, has been paid more than $100 million for providing the military with communication advice.”

“In 2013, SOCOM seeks $58.9 million for its information operations, according to the Stimson analysis, while Central Command wants $29.4 million,” USA Today reported a decade ago.

In a Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on SOCOM budget authorizations and outlays for 2020-21, the total SOCOM sums were running between $12 billion and $13 billion. So-called information operations are included in these budgets, but not itemized by the CRS. The CRS identifies successor programmes for the TRWI including Trans Regional Military Information Support Operations (MISO) whose objective is to “address the opportunities and risks of global information space.”

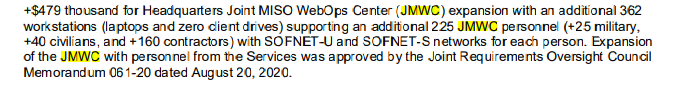

In testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee in February 2019, US Army General Raymond Thomas, then SOCOM commander, reported the expansion of his global information operations which he called “messaging capabilities”. “By April of this year, the Joint MISO WebOps Center (JMWC) will be operating in close coordination with the interagency and alongside combatant command teams to provide global messaging capabilities to a broader portion of the Joint Force and beyond CVEO themes. The JMWC will support the combatant commands with improved messaging and assessment capabilities, shared situational awareness of adversary influence activities, and the capability to coordinate internet-based MISO globally. We remain on track to achieve Initial Operating Capability in a new temporary facility by the end of FY 2019.”

According to April 2022 congressional testimony by SOCOM’s current commander, General Richard Clarke, “In Ukraine, Russia’s unprovoked, unjustified, and premeditated invasion reminds us of continued challenges to the rules-based international order. Since 2014, following Russia’s previous aggression in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, SOF supported multinational training efforts with Ukrainian SOF forces and provided Military Information Support Operations (MISO) assistance to illuminate and counter Russian disinformation. Russia’s destabilizing activities reinforce the importance of USSOCOM’s decades-long commitment to enhancing interoperability with Allied SOF throughout Europe – a critical asset in providing options for the United States and our Allies.”

Clarke acknowledged that the information operations of SOCOM have “more than doubled” since 2019.

General Richard Clarke, May 2022: “SOCOM may have to go up against an adversary more adept at info-ops. ‘There’s a reluctance sometimes to operate in that space…. As we go forward, we need to look at: what are the authorities we’re going to use? And what capabilities are we going to need as a nation to use in the information environment?’ he said. ‘I still don’t think we have all the tools that we need,’ he added. One of the tools is ‘sentiment analysis,’he said. He referred to a ‘major brand”’ that every day measures how it is faring in public opinion compared to its competitors. ‘Where is our sentiment analysis?’ He asked.”

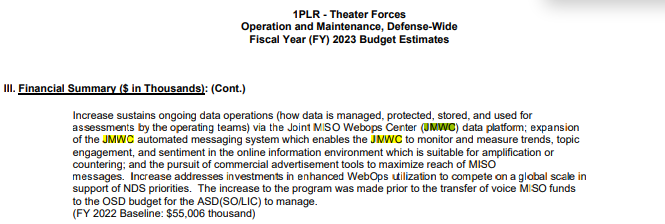

“USSOCOM has invested heavily,” Clarke said, “to expose and counter adversary propaganda and disinformation to better compete in the cognitive domain. Competitors, like China and Russia, continue to act assertively in the information ‘gray zone’ to manipulate populations worldwide. As DoD’s Joint Proponent for Military Information Support Operations (MISO) and the Coordinating Authority for Internet-based MISO, our command is adapting our psychological operations forces for the evolving information landscape. As part of our ongoing rebalancing efforts, our MISO activities to counter strategic competitors have also more than doubled over the past three years – comprising over 40% of our MISO activities worldwide in FY21. The Joint MISO WebOps Center (JMWC) continues to coordinate our MISO conducted via the internet and actively engage foreign audiences to illuminate and counter hostile propaganda and disinformation online. Since 2021, we have incorporated our first foreign partners and interagency liaisons within the JMWC.”

Precise budget money data are not openly available for the MISO operations. In this Pentagon budget summary for FY 2023, the “baseline” expenditure for MISO is reported to have been $55 million. Last year, the brain box of the entire operation, the “Joint MISO Webops Center” (JMWC) at MacDill was given a personnel, equipment and pay increase:

Source: https://comptroller.defense.gov -- page 116.

Source: https://comptroller.defense.gov/ -- page 154.

Additionally, SOCOM’s “cyberspace activities” were appropriated at $9.7 million in FY 2020, $45.9 million in FY 2022, and $39.2 million in the current financial year. The civilian staffing for the MISO operations has reached 6,900, each of whom is budgeted for an annual salary of $139,000. IT contract support services have jumped in value from $400 million in 2021 to $633 million this year. This year the transfer of “centralized MISO voice funding” from the SOCOM budget to the Pentagon, for coordination of the influence operations of each of the Army’s combat commands, has been budgeted for $56.9 million.

In May of this year, the Pentagon’s Inspector General announced it is opening an investigation “to determine whether the U.S. Special Operations Command’s Joint Military Information Support Operations Web Operations Center (JMWC) supports the combatant commander’s requirements to conduct military information support operations (MISO). We will perform this evaluation through interviews with the offices of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations/Low-Intensity Conflict, U.S. Special Operations Command, combatant commands, the Joint Staff, and DoD partners and conduct site visits at select combatant command headquarters and JMWC locations. We may identify additional stakeholders and locations during the evaluation.”