“We are at war,” Emmanuel Macron said on Monday as he outlined the emergency measures France was taking to shore up its energy supply and shelter its citizens and business from soaring costs.

For months following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the president of France, aspired to act as intermediary and peacemaker between Kyiv and Moscow. This week he and fellow European leaders became belligerents in a sharply escalating energy conflict between Russia and the west. It was time, Macron said, for a “general mobilisation”.

The Kremlin’s weaponisation of its fossil fuel has forced European governments to take drastic action, unthinkable only a few months ago, to blunt the Russian attack and shield their energy markets and economies from the impact.

Sweden and Finland had to provide emergency liquidity assistance to their power producers that were facing surging demands for collateral for their hedging operations.

Finland’s economy minister Mika Lintilä said the region could be on the verge of the energy sector’s version of the Lehman Brothers bank collapse in 2008.

Germany unveiled a second support package for households and businesses, worth €65bn, bringing to some €350bn the amount earmarked so far by EU governments to offset rocketing prices and diversify supply. Only two days after taking office as the UK’s new prime minister, Liz Truss announced a cap on energy bills for households and businesses that is expected to cost at least £150bn over two years.

G7 powers on September 2 also agreed to impose a global price cap on Russian crude oil, a bigger source of revenue for the Kremlin than gas, although it could be hard to implement and other big importers such as China, India and Turkey may refuse to take part.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, who is to outline a package of emergency measures next week, said the price of Russian gas imports should also be capped — an idea proposed by Italy’s Mario Draghi which gained support from EU energy ministers on Friday, despite fears it would provoke the Russian leader to turn off the taps completely.

Russia has been holding back gas supplies to European markets since September last year, sending wholesale prices 10 times higher, pushing inflation to 40-year highs and economies to the brink of recession. All along, Moscow denied what it was doing or said it was for technical reasons — which Brussels and member states have disputed.

This week it finally dropped the pretence. On Monday, in what looked like retaliation for the oil and gas price cap proposals, the Kremlin said gas deliveries through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, its main conduit to European markets, would only resume once the west dropped economic sanctions against Russia.

“The last mask has fallen,” von der Leyen said.

Russia is still pumping gas through Ukraine and via the TurkStream pipeline — about a fifth of the total amount it was sending in June — but the prospect of a complete stop in gas flows has arrived sooner than many in Europe anticipated.

Putin played up the threat at an economic forum in Vladivostock on Wednesday. “We will not supply anything at all if it is contrary to our interests. No gas, no oil, no coal, no fuel oil, nothing,” he said.

Moscow also received a show of support from other oil producers this week — three days after the G7’s oil price cap — when the Opec Plus group of countries, which includes Russia, agreed to shave 100,000 bpd from output.

Alexander Novak, Russia’s top energy official, crowed about the “collapse” of Europe’s energy markets. “Winter is coming, and many things are hard to predict,” he said.

However, some officials and analysts believe this may have been the week when Moscow’s pressure campaign began to lose its potency. An indefinite shutdown of Nord Stream 1, Russia’s gas conduit, was supposed to be the Kremlin’s big weapon that would send the wholesale price to new stratospheric levels. But by Wednesday wholesale prices fell below Monday’s level.

“If that’s it, then that might mean the end of the show,” said Simone Tagliapietra, senior fellow at the Bruegel think-tank in Brussels.

Confidence is growing in European capitals that Europe can get through the winter without severe economic and social dislocation or energy rationing. Von der Leyen said the EU had “weakened the grip that Russia had on our economy and our continent”.

Gas storage at facilities in the EU stands at 82 per cent, well ahead of the 80 per cent target the bloc set for the end of October. Member states have diversified supplies, increasing pipeline imports from Norway, Algeria and Azerbaijan and LNG from the US and other producers.

Before its invasion of Ukraine, Russia accounted for 40 per cent of the EU’s gas imports but now only 9 per cent, von der Leyen noted.

“Everyone expected [Russia] to get to the shut off of Nord Stream in the winter, because the winter is when they could maximise the pressure,’’ said Tagliapietra. “This acceleration of events tells us that probably the Kremlin did not factor in the possibility for Europe to come up with such a response.”

One EU official said: “Putin has not achieved his goals — our dependency on him has come down much more quickly than expected.”

Economists at Deutsche Bank now think Germany’s economy would contract by 3-4 per cent in 2023 rather than 5-6 per cent, on higher than expected storage and reduced consumption.

Still, EU leaders are also aware of the pain that will come with soaring energy bills this winter, and the escalating cost to EU governments of cushioning households from sky-high costs.

“All the member states are suffering, and they feel it could be a winter of discontent,” said the official.

With inflation expected to remain high into next year, consumers are bracing for the biggest hit to living standards in a generation as wages fail to keep pace with prices.

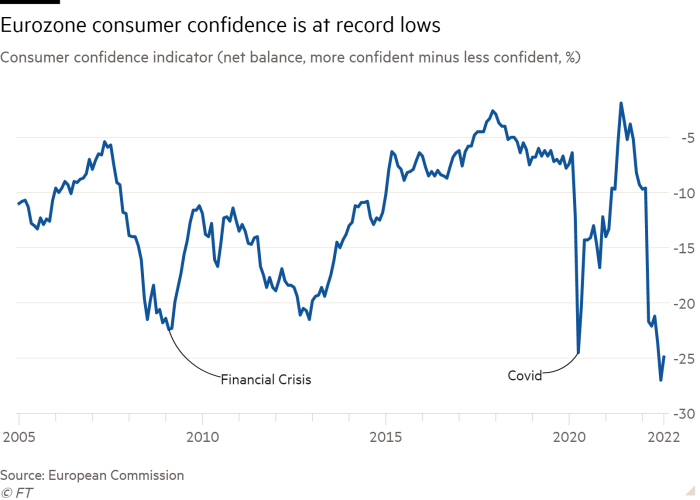

Consumer confidence dropped to the lowest level since records began in 1974 in the UK and it plunged to a near record low in the eurozone. The latest S&P Global PMI, a monthly business survey, showed business activity contracting in August in the eurozone and the UK.

The UK economy started to contract in the second quarter and even the latest government aid has not dispelled a possible recession. The European Central Bank now expects the eurozone to stagnate in the last quarter of the year and the first three months of 2023, and to shrink altogether next year in a downside scenario.

Angel Talavera, head of European Economics at Oxford Economics, said it was “inevitable” that governments would come up with larger support packages.

Roberto Cingolani, Italy’s energy transition minister, said: “For as long as we are in this terrible situation it makes sense to have extraordinary measures to protect citizens and companies.”