What is the total value for all the homes in the UK? Estimates can vary by the odd trillion or so, depending on who is doing the calculations, but this summer property portal Zoopla put the figure at a whopping £10tn.

It’s my guess that thanks to rising interest rates and the deepening cost of living crisis, this will turn out to be a record high — at least when adjusted for inflation.

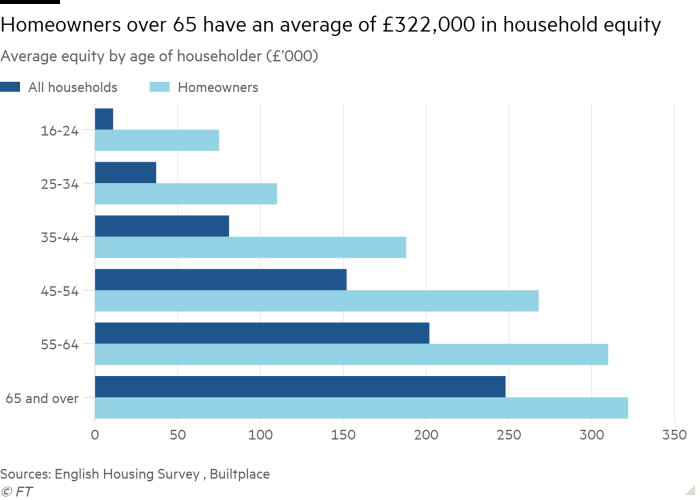

But forgetting the latest headline figure — which assumes all homes find a buyer at current prices in what is a very illiquid market — what is more telling is that housing wealth is not distributed equally. Using English Housing Survey data — which posits a much lower total amount and removes all outstanding mortgage lending — some colleagues and I calculate that homeowners aged over 65 collectively own 47 per cent of total housing equity. The under-45s own just 12 per cent. No wonder the Bank of Mum and Dad has been so popular.

Property wealth might be one of the most eye-catching of the generational inequalities in housing, but it’s not the only one: housing space has risen to the fore since the pandemic hit. At an aggregate level, there are enough bedrooms for every resident in England to have one to themselves with nearly 10mn spare — and that’s before we include the 1.1mn vacant homes.

The vast majority of these “extra” bedrooms are in homes occupied by older households (over-65s have 7.4mn of them). Many will be the bedrooms of children who have now left home, though in some cases they may be transformed into home offices or some other use that appeals to those in retirement — probably more gyms than model railways these days.

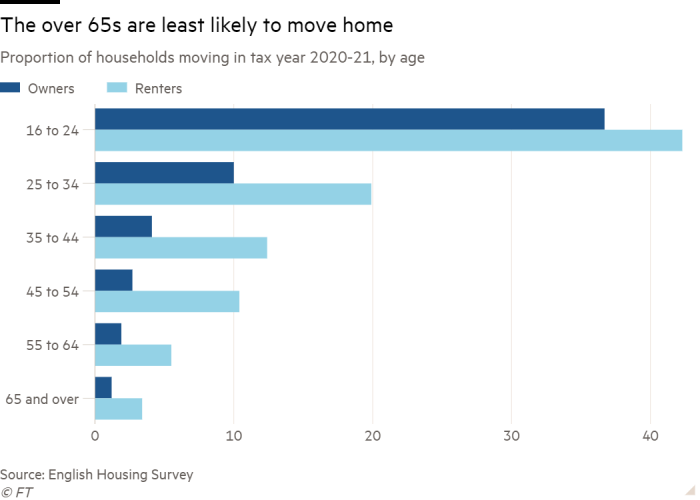

It has been regularly suggested that all these extra bedrooms could be used to ease the housing crisis — and the country would definitely benefit from a more liquid housing market with homes that are better distributed. But this is a morally and politically difficult challenge to solve. Older people are understandably less willing and less likely to move home than younger cohorts.

And this trend is true even for renters. More than a third of over-65 households have lived in their current residence for 30 or more years, irrespective of tenure. Even incentivising people to move out of their family home is fraught with difficulties and that’s before any potential inheritance beneficiaries — or children, if you prefer — get involved in the discussion.

The economics of downsizing are also challenging. While older people hold the vast bulk of housing wealth, this partly reflects the size of their generation. Most older people actually live in average-priced homes. Despite owning nearly half the total housing equity, the average figure among older homeowners is £322,000 a household.

With an average flat selling for £295,000 in 2021 and a bungalow for £337,000, there has been little financial incentive for people to downsize — even before accounting for moving costs.

However, that may be about to change, thanks to the cost of living crisis.

The country’s ageing housing stock and a lack of investment has left the UK underprepared for soaring energy prices. Around one in five dwellings in England was built more than 100 years ago, and period homes typically have much lower energy-efficiency ratings than newer homes. More than 80 per cent of homes built prior to 1919 had a low rating (D grade or below) on their Energy Performance Certificate, according to the latest English Housing Survey. Homes built between the wars — another 15 per cent of total dwellings — are not much better, with nearly three-quarters having a low rating.

It’s not just older homes that are associated with lower energy efficiency, but older households. Some 48 per cent of those headed by someone aged between 16 and 29 had an energy efficiency rating of D or lower; for the over-65s, the proportion rose to 62 per cent. While low-income and younger households might be most exposed to the cost of living crisis given less budget capacity to cut back on essentials, older households are far from immune given the poor energy efficiency of their housing.

Though energy price rises will be frozen this autumn, those in homes with the worst energy efficiency ratings will still have to pay the most. Next month, the average monthly gas bill in homes with a D-rating will be 28 per cent more expensive than an average C-rated home, according to analysis by the Resolution Foundation — a nice period home with original features and spare bedrooms could easily become a real burden to equity-rich, income-poor retirees. Whether it is enough to trigger a flood of downsizing is unclear but, even if government support eases the pressure, the challenges faced by households irrespective of income, wealth, or age might just be big enough to change people’s behaviour.

One of the challenges with modernising and improving the energy efficiency of UK homes is the investment required. More analysis in the English Housing Survey shows the majority (95 per cent) of D-rated homes lived in by older people could be improved to a C rating. However, the average cost to improve their home to this standard is estimated at £8,332. And that’s just the average: 22 per cent of households would need to spend between £10,000 and £15,000, while a further 12 per cent would need to spend £15,000 or more.

Given the costs involved, perhaps it’s time to use some of that housing equity that older households have been lucky enough to accrue and reinvest it back into their homes.

Neal Hudson is a housing market analyst and founder of the consultancy BuiltPlace

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on Twitter or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram