This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. It’s CPI day. There is good reason for optimism that inflation will continue to abate, and not just because of gas prices. But as we like to repeat at Unhedged, there is no such thing as high and stable inflation. There will be more surprises, in both directions, before the current episode concludes. Email me: robert.armstrong@ft.com.

Housing: even worse (so, better?)

The last time Unhedged checked in on the US housing market, back in June, we wrote that “housing remains the one big area of the economy that is not sending mixed signals. It just looks bad.” This is no longer true: the US housing market no longer just looks bad; now it is very bad.

“Bad” is ambiguous in this context, though. Sharp housing downturns, such as the one we are unmistakably in now, simultaneously reflect and reinforce recessionary forces. At the same time, when inflation is running wild, as it unmistakably is now, a big slowdown in real estate activity, house prices and rents might be strong medicine. Rent inflation is the sticky kind of inflation central bankers hate — it goes hand in hand with wage inflation. Housing needs to cool if the Fed is to be satisfied.

More on that shortly. First, let’s survey the wreckage:

-

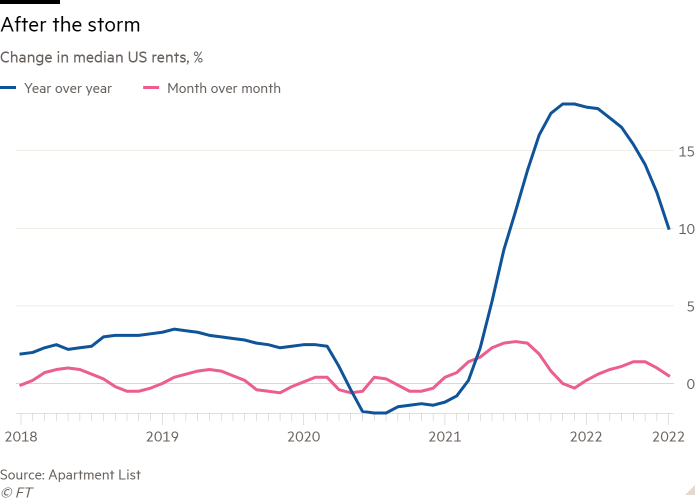

Rent growth has turned over, hard. This is reflected in the real-time indices maintained by listing sites such as Apartment List, Redfin and Zillow. Below is Apartment List’s. Month-over-month rent inflation is back into a historically normal range, and year-over-year will be there soon, on current trends

-

Home price growth, on more-or-less official but lagging indicators, such as the National Association of Realtors report and Case-Shiller indices, is decelerating but still strong. More timely measures remain elevated on an annual basis, but on a month-to-month basis, many are all the way back to normal (see Zillow’s price index below). House prices are still wildly high, but the inflation is ending.

-

In many regions, at many price levels, prices are already falling. Unhedged’s friend Rick Palacios of John Burns Real Estate Consulting notes that, in his firm’s August price survey, prices fell in 98 of 140 covered markets fell on a month-to-month basis. “The pace of the declines is accelerating,” Palacios says. Seattle’s decline is the worst; prices there are down 8 per cent from earlier this year. Moderate house price deflation on the national level seems entirely possible before too long.

-

If prices are just starting to edge down, sales volumes are already through the floor. Existing home sales were down 20 per cent year over year in July. New home sales were down 30 per cent. Mortgage applications keep on tumbling too.

Steven Blitz, the head US economist at TS Lombard, argues that house prices, and indeed financial asset prices, have to fall hard if inflation is to come under control.

He argues that the economic cycle that started over a decade ago, as we emerged from the financial crisis, was unusual in that it was not a credit cycle, but an asset cycle. “Typically, leverage increases in an expansion and decreases during a recession, but we had a ten-year expansionary period in which households and businesses continued to de-lever, and, after an initial surge of spending, the government did too, right through 2019,” he says. Wealth was created through the cycle not by credit expansion but by asset price inflation. The result, he says, is that the sensitivity of the economy to the Federal Reserve’s rate increases is going to be different this time. Deleveraging is not going to slow the economy enough to stop inflation. Falling asset prices will have to do the work.

If Blitz is on to something here (I think he is, though I am not totally convinced that companies have reduced leverage) and the Fed shares this view (he thinks it does), the withering housing market is good news. It is part of what the Fed needs to see before it will be comfortable slowing the pace of policy tightening.

But things are not so simple. I wrote in February about how home prices and rent inflation will take a long time to work their way through the official CPI data — a year or more. What is more, the housing inflation we have already seen may continue to support wage inflation. Strategas economist Don Rissmiller sums up that connection pithily: “Companies will pay what it costs workers to live where the companies need them to be.” The process of increasing workers wages to that level may take time, though. In the meantime, the Fed might keep tightening into a deep recession.

This is a particular instance of a general question which, Rissmiller points out, is as important as any facing markets. When does the Fed declare victory? Official shelter inflation data may be falling soon. But it will be a while before it is all the way back to normal. The same goes to other categories. Some prices may never return to the soft trends that held in the days of ample cheap labour, ample cheap energy and wide-open global supply chains. Is 3 per cent-ish inflation enough for the Fed? Or will it fight all the way down to 2 per cent? If the latter, a deep recession seems increasingly likely.

One good read

“Trump is widely hated by many, of course, but equally loved by many. Everyone hates Jared.”