Inflation is the wrecker of worlds. It destroys purchasing power, increases the signal-to-noise ratio of prices critical to entrepreneurs and business managers, and distorts accounting records. Its uneven effects may make unprofitable companies and projects look profitable, and profitable ones appear to be losers. When persistent, it becomes a major drag on economic growth, increases unemployment, and rewards borrowers at the expense of lenders. And depending upon its origins, inflation may also facilitate lavish government spending beyond what tax and tariff incomes would otherwise permit.

But a nation needn’t experience a Weimar-like explosion of hyperinflation for all manner of ruinous effects to materialize. Comparably low levels of inflation will do the trick as handily as the handful of rare, extreme episodes that have captured the attention of economists and the fascination of internet wags. A search for the phrases “hyperinflation (is) right around the corner,” ‘hyperinflation is coming,” and “impending hyperinflation’ on Twitter exposes a low-level buzz around the idea that any surge in the general price level is likely to beget a spectacular disintegration of the price system. That is not impossible, but it is exceedingly improbable, for a handful of reasons.

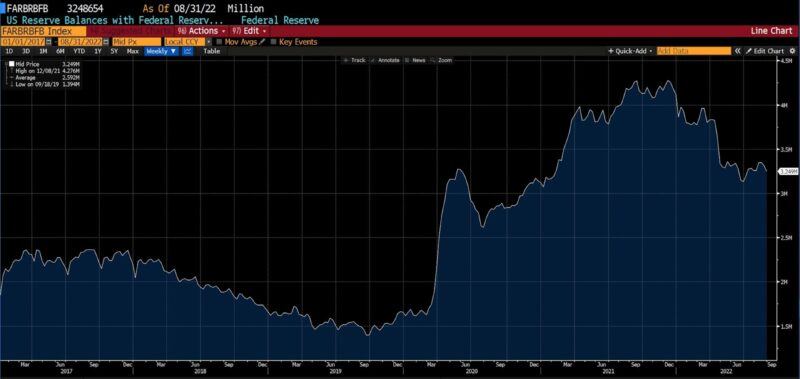

- The Fed’s 2008 move from a floor system to a corridor system involves paying interest on reserves (IOR). This virtually guarantees that a large portion of the money stock is staying put at the Fed, not being loaned or chasing goods and services. That amount currently stands at roughly $3.2 trillion. If necessary, the Fed could raise the “internal” rate of interest, luring more money in pursuit of essentially risk-free returns.

US Reserve Balances with Federal Reserve Banks (2017 – present)

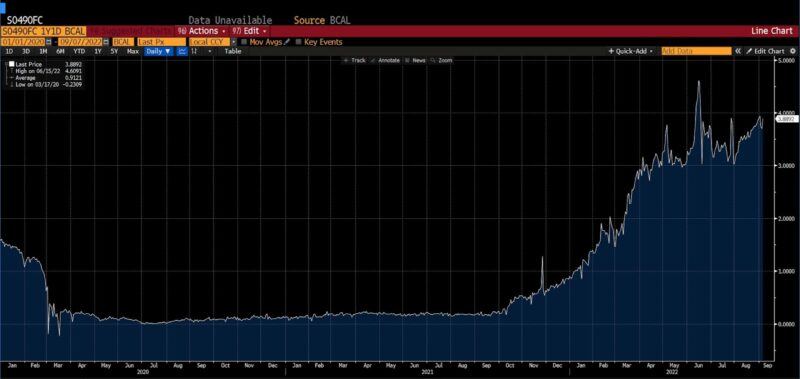

- The Fed is currently predicting that inflation will come down next year, and market participants currently expect the fed funds target to only reach about 3.8 percent by the end of 2023.

Market Implied Policy Rates, 1 year

- There is also, within the Fed, a goal of rate normalization, given that 144 of the last 173 months (back to January 2000) have been at a sub-one-percent level nominally, negative in real terms. That may be wrong, but in light of Volcker’s tenure (within which rates were raised to over 20 percent) there’s still a lot of policy headspace for the Fed to operate within. If inflation were to continue to rise or even accelerate, the Fed would simply chase it up with higher and higher rates, or increase the rate of the balance sheet unwind, currently removing some $95 billion per month from the US economy. It could also engage in other, more unconventional operations. An exceptionally radical approach to dealing with runaway inflation, and arguably the antithesis of “helicopter money,” was untaken by the Afghanistan central bank for other reasons several years ago.

- Presently there are indications that markets and consumers expect inflation to be high for a while and then recede. If markets prove wrong, arbitrage opportunities will emerge. Consumer expectations may be wrong, but at present they do not indicate that persistently high inflation such as occurred in the 1970s (and which was also not a hyperinflation) is likely. The spread between the current generic 5 year US government note and the 5 year Treasury Inflation Protected Security (TIPS) yield currently estimates an average annual inflation of 2.52 percent through 2027.

5 year US Treasury-5 year TIPS yield spread (April 2022- present)

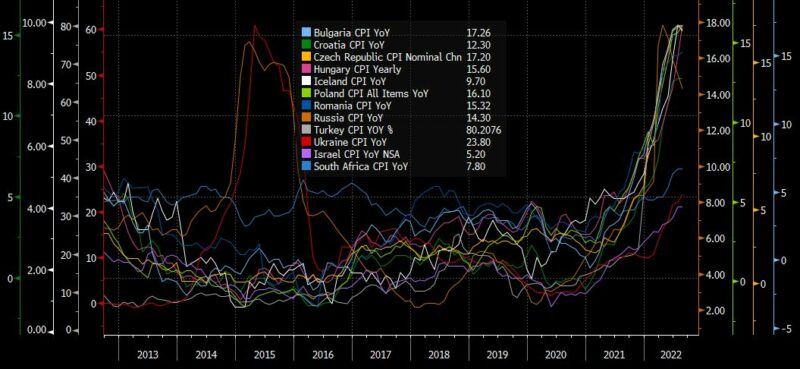

- Unlike the Zimbabwean dollar or the Venezuelan bolivar, the dollar is more than a currency. It’s a safe-haven asset and a global unit of account. The demand for US dollars is extremely high, although monetary technocrats would be wise not to test the limits of that adage. The global demand for dollars results in the effective exportation of a portion of expansionary monetary policy’s inflationary effects. Although that sounds like good news for Americans and not-so-good news for downstream users of dollars, in many emerging markets even inflationary US dollars are likely to be less inflationary than domestic currencies.

Emerging market year-over-year inflation rates (2012 – present)

- Most previous outbreaks of hyperinflation have begun with colossal, emergency-driven policy partnerships between fiscal and monetary authorities. Two common themes are an order by a head-of-state or executive body to print money to meet fiscal obligations on an unlimited basis, or to monetize an unsustainable debt load. While neither are impossible within the United States, the former is currently illegal, and the second is not, at present, a matter of particular exigence. But these are reasons why Fed independence and reducing the outstanding US debt are critical.

None of this should, although it likely will, be construed as either dismissing the dangers of inflation or giving credence to the Fed’s inflation-fighting expertise. The superlative hallmarks of hyperinflationary episodes are exciting to some, carrying unwieldy piles of physical currency to buy simple goods, prices changing hourly, and so on, but completely unnecessary for inflation to destroy economic calculation and peaceful, voluntary exchange. In England, at present, the harmonized Consumer Price Index is currently up 10.1 percent year-over-year, which is nowhere near the rates Philip Cagan classified as hyperinflationary in 1956, but destructive nevertheless. The pursuit of sound money is more profitably directed at identifying profligate monetary policy measures, rather than the consequenceless prediction of extraordinary, and extraordinarily unlikely, outcomes.