Executives at publicly traded US companies are becoming increasingly worried about the spectre of a further escalation of tensions over Taiwan, a major supplier of crucial components like semiconductors.

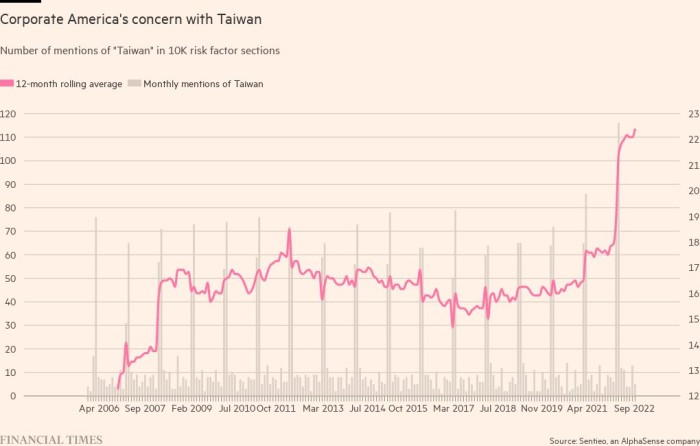

The number of annual regulatory filings citing Taiwan as a risk factor has risen significantly over the past 12 months, according to Financial Times calculations based on Sentieo data. In March, a popular time for releasing so-called “10-k” reports, 116 companies mentioned Taiwan as a risk to their business, and the rolling 12-month average this month reached its highest level in at least 16 years.

Technology companies represent the sector most concerned, with those in the semiconductor industry raising the loudest alarm. This is because Taiwan, which is the biggest producer of the most advanced chips, is rapidly becoming one of the world’s most dangerous geopolitical flashpoints. The fear is that in the event of a conflict with China, US firms will be unable to get the microchips needed to make smartphones, electric cars, new weapons, computers industrial machines, and even medical devices. Healthcare is the second most-concerned sector.

“A ‘de facto’ blockade by Mainland China’s regular military exercises would create bottlenecks in fast-growing sectors dependent on semiconductors, such as high performance computing, internet of things, data centres and electric vehicles,” Alicia García-Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at French bank Natixis, said.

In a sign of the potentially wide-ranging corporate effects, a clutch of chief executives at big US banks told Congress this week that they would comply with any US government demand to pull out of China if Beijing were to attack Taiwan. The remarks came just days after US president Joe Biden said the US would defend Taiwan from a Chinese attack.

The median US company had only had five days’ worth of chip inventories in 2021, down from 40 in 2019, according to a study the Department of Commerce.

At the beginning of August, Biden signed the Chips Act, which will provide $280bn in funding to prop up and kick-start domestic semiconductor manufacturing and research.

“The US will put more pressure on key suppliers to ban exports to China and develop production in its own market with industrial policy tools, such as the Chips Act and a push for friend-shoring,” García-Herrero said.