Executive Summary

In a now-famous 1970 paper, economist George Akerlof used the market for used cars to demonstrate the negative effects that can occur when there are significant information asymmetries between buyers and sellers of a good or service. He highlighted the market for used cars at the time, where, because consumers could not be sure of the quality of a used car they were offered, they were only willing to pay the price of a car in average condition, driving out sellers of high-quality used cars (“peaches”), who were not willing to accept the average price for their above-average product. At the same time, sellers of low-quality cars (“lemons”) were incentivized to enter the market, as they could receive a price greater than the actual value of their used car. This information asymmetry led to a negative cycle where more low-quality cars would enter the market, driving down consumer trust (and the price they were willing to pay) and even leading to a market of lower-quality cars.

The financial advisory industry is not immune to the same problems faced in Akerlof’s used-car market. Given the wide range of professionals who can call themselves ‘financial advisors’ – from someone whose business is selling insurance policies to a financial planner who sells financial advice itself – consumers can have difficulty understanding the type and quality of service they will receive from a given ‘advisor’. And just as the uncertainty of quality reduced the car buyers’ willingness to pay for high-quality cars in Akerlof’s analysis, the wide variance in advisor quality can also be likely to lead to a lack of trust among consumers.

But this also suggests that if standards in the market for advisors were raised (thereby increasing consumer trust), exceptional advisors could spend less money on differentiating themselves from advisors with lower standards, creating the opportunity for reduced marketing and business expenses that could be passed along in the form of lower costs for consumers (potentially opening up advice to a wider pool of clients!) and even allow for higher-quality advisors to enter the market. In fact, even a relatively modest shift to a higher-trust environment (which may be achieved by enacting higher standards) that just partially reduces the incredibly high client acquisition costs of financial advisors could more than offset the entire cost of fiduciary liability insurance from those higher standards!

In his paper, Akerlof suggests three strategies that could be used to counteract the effects of quality uncertainty and increase consumer confidence: licensing, quality guarantees, and branding. Accordingly, advisor licensing could mean establishing a requirement involving a professional designation like the CFP certification for those who provide financial advice. A quality guarantee could be implemented through a broad-based fiduciary standard (as advisors are understandably unable to offer outright performance guarantees), which can increase trust among consumers. And when it comes to branding, limiting the use of the title “financial advisor” and “financial planner” to those who are solely in the business of providing advice (rather than primarily selling products) and who meet certain competence and ethical standards would increase consumer confidence as well.

Ultimately, the key point is that information asymmetries that reduce consumer trust are common in the financial advisory marketplace, and raising industry standards of conduct could not only improve consumer confidence in advisors, but also reduce marketing costs for advisors trying to gain consumer trust. Because, in the end, helping consumers differentiate between advisor ‘peaches’ and ‘lemons’ can improve the public’s experience with financial advice and, at the same time, reduce marketing expenses for advisors, which in turn can reduce the total cost of advice and attract prospective clients from a broader pool willing and able to work with an advisor, as access to quality advice increases as well!

Over the past several decades, consumers have gained more access than ever to information about what they’re buying. From government mandates regarding the details of what goes into products to websites that aggregate and report out on product details and comparisons, and simply a consumer preference for greater transparency that has led product manufacturers to release more and more of their own details regarding their products and what goes into them, buyers have more information than ever before when it comes to making a purchase.

When it comes to buying used products, though, the landscape can be more challenging. In such cases, the seller – who currently owns and has been using the product – will have more information about its condition than the buyer. For example, someone selling a used television will have a good idea of how long it has been used and its current condition, while the buyer will know little about its past. The used car market has long struggled with the fact that sellers know how much time and effort they’ve really put into maintenance to keep the car in good condition… or not. From the buyer’s perspective, in the absence of information confirming the condition of the television or the used car, that buyer is likely to ask for a steep price discount compared to a new television or car (no matter the true condition of the used good), in part to protect themselves from the uncertainty due to their lack of information.

This kind of ‘information asymmetry’ is common in the context of service businesses as well, where the buyer can’t just look up the ‘product specifications’ to understand the quality of the service they are considering. Because service experiences can change over time based on the service providers themselves as the people in the business grow and develop (or experience attrition or turnover). The knowledge gaps arising from information asymmetry have at least been partially plugged by review sites that allow others who have used the service provider to share their experiences. Though it’s still never clear whether the next buyer will have the same experience or not.

This information asymmetry of service providers is especially challenging when hiring ‘expert’ services. From doctors to lawyers to accountants, the nature of the professional’s expertise means there’s virtually no way for the typical consumer to know if they’re really a ‘good’ expert or not; after all, almost by definition, hiring an expert means hiring someone who knows more than you do (which means you’d have no way to know if their expertise is really up to snuff).

And the information asymmetry of hiring experts is unfortunately quite present in the financial advisory industry as well. Not only is it challenging for consumers to understand which financial advisors are ‘most expert’ around their money issues, but because a wide range of professionals can call themselves “financial advisors” (regardless of whether they have any actual training in finances or advice, and whether they’re compensated for that advice or for selling a product), consumers may struggle to tell the difference between one whose business model is based on the sale of financial products and another whose product is the advice itself.

Which means – similar to the information asymmetry of the used television or the used car – either that consumers are not willing to pay as much for financial advice (given the risk that they pay a lot only to find out that the advisor isn’t very good), or that advisors who stick to their ‘full’ fee must then expend far more in marketing costs to persuade prospective clients to pay their fees in full (which in turn further drives up that fee to cover its marketing costs!).

Which is important, as both these scenarios suggest that information asymmetry can result in a higher cost for financial advice and, conversely, that if consumer trust in advisors were raised by reducing that information asymmetry and their uncertainty about advisor quality, advisors could spend less time (and money) trying to convince potential clients of their qualifications and more time on financial planning itself, reducing costs and increasing access to good financial advice!

Information Asymmetries and The Market For “Lemons”

While information asymmetries have existed for centuries, the topic was explored in depth by economist George Akerlof in a 1970 paper, “The Market For ‘Lemons’: Quality Uncertainty And The Market Mechanism” (Akerlof would later win the Nobel Prize in economics for his work on the subject). In the paper, Akerlof discusses the market for used cars and the negative effects that can occur when there are significant information asymmetries on each side of the buyer-seller transaction.

How Information Asymmetries Can Drive Down Product Quality

In the market for used cars, sellers know significantly more about their products than buyers. For example, one used car might have been regularly maintained and always kept in a garage, while another seemingly identical car might have been in an accident or a flood that caused damage not apparent to even a trained mechanic. Because consumers are not able to tell whether a used car is of high quality (labeled a “peach” in Akerlof’s paper) or low quality (a “lemon”), they will be reluctant to pay the true value of the “peach” because they cannot be sure that it’s not really a “lemon”.

For example, for a given car model and mileage, a “peach” might be worth $15,000, a car in average condition would go for $10,000, and a “lemon” would only fetch $5,000. If a consumer is unable to tell the true condition of the car, they may have no choice but to assume it is of average condition and be willing to pay $10,000 for it, even if its true condition ‘should’ have merited the top $15,000 price.

If a consumer is only willing to pay the price of a car in average condition – because they can’t actually tell if it is a ‘peach’ or if they may be overpaying for a ‘lemon’ – then sellers of ‘peaches’ will have to choose between selling their car for a lower price than its true worth or not selling it at all. On the other hand, sellers of ‘lemons’ will be more than happy to sell their cars for a price that is significantly more (at $10,000) than the actual value of their vehicles (only $5,000 with the poor condition/damage). However, as fewer owners of ‘peaches’ decide to sell their cars (because they would otherwise have to accept a below-market price) and more owners of ‘lemons’ sell theirs (attracted by the ability to receive the average-quality price for their below-average-quality car), the overall quality of used cars on the market declines.

As this pattern continues over time, only the worst-quality cars will remain on the market, and with experience, consumers eventually adjust their willingness to pay downward as they realize that most cars on the market are ‘lemons’. Which, in turn, drives out even the sellers of average-quality cars, and the overall quality of used cars declines even further.

At the extreme, almost no used cars would be sold at all, because almost all of them turn out to be ‘lemons’, and consumers at that point know that they are likely to be in poor condition (because those are the only car-sellers that remain).

Nerd Note:

While the market for ‘lemons’ in used cars is the most well-known example from Akerlof’s paper, he also identified other areas where information asymmetries can decrease market quality. These include insurance (as when individuals know more about their own health than do insurance companies, healthier individuals end up paying more in premiums than they would otherwise because insurance companies have to price up for the risk that there are undisclosed health issues), and lending in developing countries (where lenders who cannot assess creditworthiness charge higher levels of interest to protect against potentially bad credit quality that might, in fact, have been good).

Uncertain Quality In The Advisor Marketplace

The financial advisory industry is not immune to the same problems faced in Akerlof’s used car market. Given that a wide range of professionals can call themselves a ‘financial advisor’ – from someone whose business is selling insurance policies, to a financial planner who sells financial advice itself – it can be challenging for consumers to understand the type and quality of service they will receive from a given ‘advisor’.

This likely contributes to the relatively low percentage of Americans who work with an advisor; according to a YouGov poll of American adults, when seeking financial advice, 22% of Americans turn to a financial advisor, while 28% ask their partner, 21% look to the Internet, 21% ask no one, and 20% seek advice from their parents (and while perceived ability to afford an advisor or other factors might also affect a consumer’s calculus on who to turn to for advice, the fact that consumers are similarly disposed to ask no one for advice as they are to consult a financial advisor shows how the title ‘financial advisor’ has been undermined!).

And just as quality uncertainty reduced willingness to pay for high-quality cars in Akerlof’s analysis, the wide variance in advisor quality likely leads to a lack of trust among consumers; 2021 research from Morning Consult found that only 36% of U.S. consumers surveyed tend to trust investment and wealth management companies (while the same amount said they outright distrust these companies, and the remaining 28% did not have an opinion). Further, only 52% of consumers said they trust investment and wealth management companies to act in the best interests of consumers, a lower percentage than all other financial institutions in the survey.

Similar survey research released earlier this year by consulting firm Edelman found that 48% of U.S. consumers trust financial advisory businesses to do what is right, lower than both banks and credit card companies (where 54% of respondents said so); notably, out of 16 total industries, financial services is one of the least trusted industries in Edelman’s global survey, only outpacing social media.

At one end of the market for financial advice are advisors providing advice on a fiduciary basis, typically charging on a fee-only basis. On the other end are product salespeople who are widely criticized in the media because of those who recommend high-commission products of low quality (as the high embedded fees make them less competitive than alternative less-commission-laden financial products available to consumers). Yet both fiduciary-based financial advisors and product salespeople market themselves as “financial advisors”, and both claim they operate in the “best interests” of their clients (either under a bona fide fiduciary standard or under the SEC’s lesser Regulation Best Interest); as a result, consumers struggle to tell them apart and often end out with an undesirable experience (as the trust data on the financial services industry clearly shows).

Yet, as predicted by Akerlof’s research in the “Market For Lemons” article, the advantages for non-advisor salespeople marketing as “best-interest financial advisors” have accumulated over time. As similar to used car dealers selling ‘lemons’ for average prices (and enjoying outsized profits at the expense of their customers), selling high-commission products has similarly enriched product manufacturers and distributors that sell products under the guise of financial advice. Which, in turn, provides them with even more financial wherewithal to invest the profitability of their commissions into marketing strategies to generate more sales.

For instance, spending $10,000 on a dinner seminar or direct-mail campaign is challenging for financial advisors who ‘only’ get two new clients with $500,000 accounts each… which, at a ‘traditional’ 1% AUM fee, will generate only $2,500 in fees over the next 3 months and will take an entire year of providing service just to recover the cost. On the other hand, ‘advisors’ who sell higher-commission products that pay 5% or more upfront may generate $50,000 in compensation in a matter of just a few weeks. Which not only comes at the expense of clients who end out paying 5X as much over the coming year, but also provides the salesperson with enough funding to run 5 more dinner seminars next month to repeat the cycle!

In such scenarios, like the sellers of ‘lemons’, who were incentivized to enter the market because they could sell their below-average-quality ‘lemon’ cars for the price of a car in average condition, the profitability of aggressively marketing high-commission products fuels more such marketing, increasing the number of consumers being sold low-quality products, reducing the average quality across the entire marketplace just as Akerlof predicted.

In the context of financial advisors, this market environment can eventually lead to a situation where an advisor either is compelled to begin selling high-commission products themselves in order to bring in enough revenue to be able to pay the necessary marketing expenses to get more clients, or alternatively is forced to have high minimum fees or high asset minimums to ensure that they are compensated for the now-significant costs of client acquisition (which are driven up by the pressure to compete with the marketing expenditures of product salespeople).

Which is exactly how it’s played out in financial services, where, according to Kitces Research, the typical Client Acquisition Cost is now more than $3,000 just to get a single client (thus explaining why advisory firms increasingly are setting multi-hundred-thousand-dollar asset minimums), and newer advisors find it almost impossible to even get started because they don’t have enough starting capital to absorb the tens of thousands of dollars in marketing costs it will take to reach a critical mass of clients. And in the end, the new advisors who survive long enough to be successful in such an environment are not those who have the greatest expertise and provide the best financial advice to their clients, but the ones who are most adept at selling enough higher-commission products to reach financial sustainability most quickly.

Contrast this situation to doctors, whose credentials and licenses demonstrate that their services are of a certain level of minimum quality. Similarly, the length of training doctors go through also screens out a high volume of otherwise low-quality doctors who might have been attracted by their strong salaries but couldn’t make the cut. Because of this, the overall quality of doctors may still vary, but the variance is all above a comfortable minimum level of quality… which means new doctors can launch a medical practice and have prospective patients be willing to seek them out (even as relatively new doctors) rather than needing to spend all their time and dollars marketing for their initial patients (mailers advertising a steak dinner offered by a primary care physician are rare!). Which instead allows the new (and existing) doctors to focus more of their time and money on what they do best: serving patients well.

How Raising Standards Could Reduce The Cost Of Advice

As Akerlof’s research shows, a market with significant information asymmetries between buyers and sellers tends to hurt both consumers (who have to select from a pool of increasingly low-quality goods) and sellers of high-quality goods (who have a difficult time selling their products at a profit, given consumer mistrust and the marketing costs needed to differentiate themselves), while only benefitting the sellers of low-quality goods (who continue to drag the standards down until eventually consumers so distrust them that the market for that good or service collapses altogether).

But what this also means is that if market standards were raised, reducing the presence (and profitability) of low-quality providers, the sellers of high-quality goods could spend less money on differentiating themselves from those of lower low-quality and, at the same time, it could open the opportunity for reduced expenses for high-quality services that could be passed along in the form of lower costs for consumers. Which, in turn, can then create a virtuous cycle, where more high-quality sellers enter the market, driving up consumer confidence in the industry and reducing the percentage of purveyors of low-quality goods.

This is precisely why all recognized and bona fide professionals have minimum standards of competency and conduct; while in many cases, additional regulation raises costs, in markets with high information asymmetry (like most professional services), higher standards can actually reduce costs and increase access by increasing consumer trust.

Reducing The Number Of “Lemons” In The Financial Advice Marketplace

When a consumer meets with someone whose business card says they are a ‘financial advisor’, there is a great deal of uncertainty about the quality of advice and service the consumer will actually receive. Given that advisors have a wide range of education, compensation practices, and potential conflicts of interest, it can be challenging for consumers to find an advisor who will provide them with the best possible advice (or even whether the advisor is in the business of advice, versus product sales). This can (and does!) discourage consumers from seeking advice in the first place, as they are unsure whether they will receive sound guidance and fair treatment from their advisor, resulting in a consumer trust level noted earlier that is far below other industries and other recognized professions.

For example, the examination requirements for financial advisors who sell investment products for a commission (e.g., Series 7 and Series 63 exams) or those who sell insurance products do little more than test basic product knowledge and the awareness of applicable Federal and state laws, rather than requiring substantive education in financial planning itself. In fact, astonishingly, the regulatory exams to become a “financial advisor” do not in any way test competency in personal finance or advice at all! Yet these individuals often hold themselves out to the public as advisors that can manage the breadth of a consumer’s financial issues (almost inevitably leading to at least some bad client experiences when the ‘advice’ they receive is not up to the standard they were expecting because it came from someone with no training or experience!).

This can be contrasted with the education and examination requirements to attain the Certified Financial Planner (CFP) certification, which address a much broader range of personal financial issues an advisor might face with a client, while the experience requirement to become a CFP professional also helps ensure that advisors have real-world experience with financial planning before holding out to consumers as being certified. If all advisors were required to have this minimum level of financial advice education, consumers would have more confidence that the person they are dealing with has a certain baseline competency in the range of personal finance issues (reducing the magnitude of and drag from the otherwise high level of information asymmetry between the consumer and the advisor about the advisor’s capabilities).

Another area of financial advising that often involves information asymmetries is advisor compensation. For instance, while many fee-only advisors post their fee models directly on their website, the compensation for financial product salespeople is often opaque. So, while a consumer might not pay an explicit fee for the advisor’s services, they will still ultimately pay in the form of embedded fees in investment or insurance products (which are used to recover the company’s commission costs).

Which means that while the advisor is well aware of the fees (which can make up the bulk of their compensation), consumers often have to put in significant legwork to determine how much purchasing the recommended product will cost them (and can lead to disappointment in the long-run if they realize that they ended up paying more than they were willing to pay, reducing industry trust and willingness to pay in the future as a result of the information asymmetry).

Finally, there is an information asymmetry between advisors and consumers regarding the conflicts of interest advisors face. For example, fee-only advisors (while not immune from conflicts of interest) will typically be impartial about their investment product recommendations, while commission-based advisors have an incentive to recommend products that will increase their own compensation (or may even be outright required only to sell certain products that their companies manufacture and make available for sale).

Notably, consumers are cognizant of these fundamental differences between advisors and salespeople and do infer roles by the titles that advisors use. But again, when advisors use “financial advisor” and “financial planner” as ubiquitous titles regardless of whether they’re actually functioning in the role of advisor or salesperson, consumers cannot always clearly tell the difference due to the information asymmetry. Which, in the end, can lead to low-quality providers getting a disproportionate amount of market share and the “Market-For-Lemons” downward cycle for consumers seeking advice.

Altogether, these information asymmetries between advisors and clients can hinder consumer confidence in financial advisors as a whole and leads higher-quality advisors (in terms of knowledge, clarity of compensation, clarity of role, and attendant conflicts of interest) to have to spend more marketing dollars to differentiate themselves from advisors offering a potentially lower-quality ‘product’ (an additional marketing cost the high-quality providers must bear while actually selling services that aren’t as profitable due to their higher quality and lower cost).

Which, again, means that taking steps to reduce these asymmetries not only could boost consumer confidence and increase the prevalence of high-quality advice, but can also actually lower marketing costs along the way, which brings down the total cost of advice!

How Advisor Marketing Costs Typically Swamp (Fiduciary) Liability Expenses

If the financial advisory industry were to raise its standards (e.g., by improving advisor education, transparency, and abiding by a fiduciary obligation to clients), consumer confidence in the profession would almost certainly increase, and more would likely choose to work with an advisor. But an important question is what effect would increasing standards have on the potential legal liability exposure for advisors and their firms?

When regulators have proposed raising advisory industry standards in the past (e.g., the Department of Labor’s failed attempt to impose a fiduciary obligation on those advising on retirement accounts), representatives of the financial products industry have argued that increased litigation expenses from consumer lawsuits alleging violations of this higher duty would be passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices (and some advisors leaving the market), giving fewer lower-cost options to consumers looking for advice.

But this perspective ignores the potential benefits of higher standards for the industry – vis-à-vis the “Market For Lemons” effect – and how enhancing industry trust, which makes it easier for advisors to attract clients, can result in cost savings (that can be passed on to their clients).

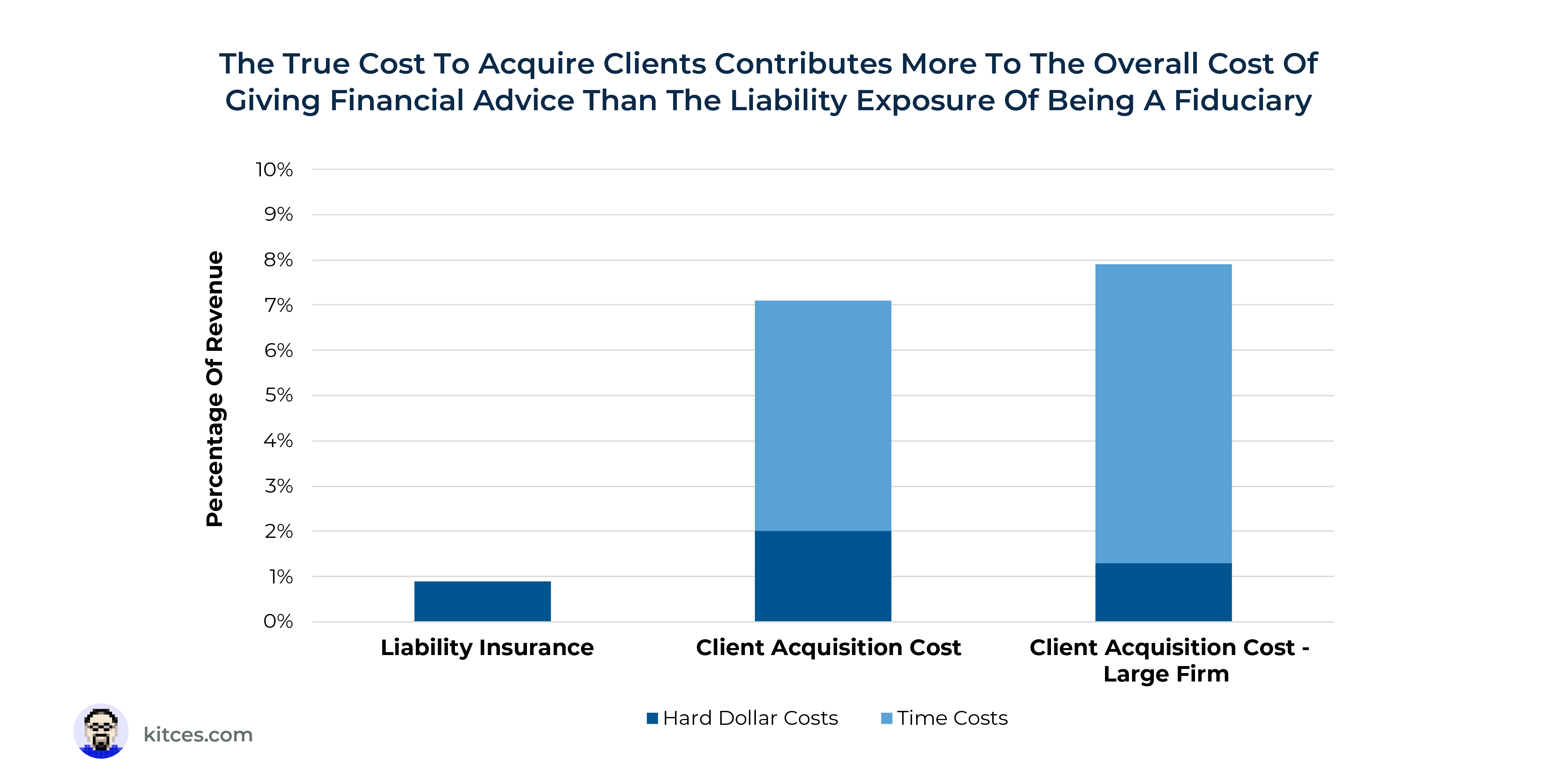

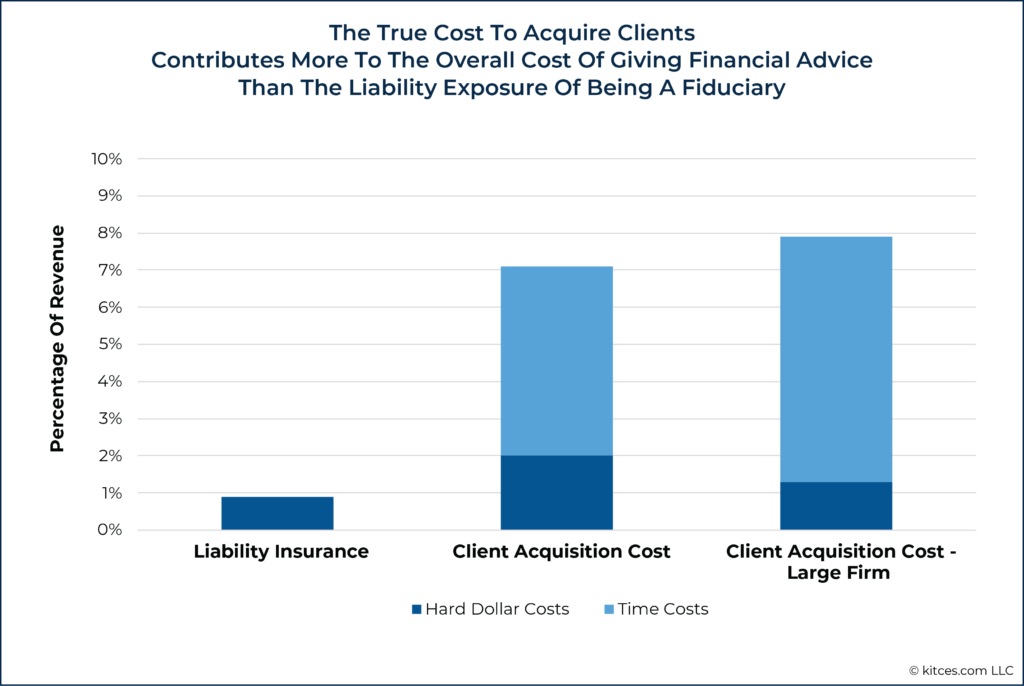

For example, according to the 2021 InvestmentNews Pricing and Profitability Study, RIAs (which are bound by a fiduciary duty) spent 1.5% of revenue on marketing and business development, compared to 0.9% of revenue spent on business-related insurance (which includes Errors & Omissions policies purchased to cover exposure to potential fiduciary-related lawsuits). And notably, this figure only includes the hard dollar cost of marketing; when the costs of the advisor’s time are factored in (which is nearly 70% of the total expense), the average client acquisition cost of an established financial advisor is $4,056, according to the latest 2022 Kitces Research on Advisor Marketing, which could represent nearly all of the revenue the client generates in their first year!

In other words, because advisors typically spend several multiples as much on marketing from their own time compared to what they spend using hard dollars, the true cost of advisor marketing is nearly 7.1% of revenue (rising even higher for larger practices)!

In sum, the data clearly indicate that in the current low-trust marketplace for financial advice, the cost to acquire clients (at least in part due to low industry trust) is far more of a contributor to the cost of advice than the liability exposure of being a fiduciary!

Which means even a relatively modest shift to a higher-trust environment – by enacting higher standards that just partially reduce the incredibly high client acquisition costs of financial advisors – could more than offset the entire cost of fiduciary liability insurance from those higher standards! Because consumers would have increased confidence that they are dealing with a qualified, transparent advisor who will work in their interests, a smaller marketing budget (in terms of time and hard dollars) could focus on what makes an advisor’s service offering unique (e.g., their client niche) rather than also having to first overcome negative perceptions of their trustworthiness.

These cost savings could then lead to reduced client fees, potentially opening up advice to a wider pool of consumers (the opposite result from what opponents of higher standards argue!). Because as the current marketplace data already shows, the legal liability costs of higher standards for existing fiduciaries already pales in comparison to the higher marketing costs that have resulted from an industry where non-fiduciary salespeople have also been permitted to market as “financial advisors”.

How The Financial Advice Industry Can Break Out Of The Low-Trust “Market-For-Lemons” Trap

Given that information asymmetries in financial advice can lead to a low-trust environment that allows low-quality sellers to thrive while making it more expensive for high-quality goods and services providers to market and attract clients (while simultaneously making it harder for them to charge full price for their value), it is important to consider ways to break out of this ‘trap’ – both for the benefit of consumers (and advisors offering a high-quality product) as well as the overall health of the advisor marketplace.

How To Counteract The Cost Of Information Asymmetries In Financial Advice

In his paper, Akerlof suggests three strategies that could be used to counteract the effects of quality uncertainty and increase consumer confidence: licensing, quality guarantees, and branding. While he considers a range of other low-trust markets, these areas, in particular, can be applied to financial planning as well.

(Better) Licensing For Financial Advice

Licensing of a service provider signals to consumers that the service provider has attained a certain level of proficiency, governed by a regulatory organization that can enforce and establish consequences for those who don’t adhere to the requisite standards.

For example, doctors and nurses have rigorous education and examination requirements that provide consumers with confidence that they have, at a minimum, a reasonable level of proficiency. This is probably one of the factors that leads them to rank at the top of Gallup’s list of honesty and ethics of certain professions (and speaking to what consumers think of those focused on commissions, car salespeople rank just above lobbyists at the bottom of the list).

Notably, as financial advisors, we do have a licensing requirement, but our licenses are built around what was originally a standard for salespeople, which means that licensing exams were designed to test whether we understood the nature of the products we would be selling and the laws that would apply to us when selling those products. However, unlike other recognized professions, licensing for financial advisors does not require any demonstration of experience or competency in personal finance or the delivery of advice itself.

What would an alternative Akerlof-style level of licensing entail? It could mean establishing a professional designation, like CFP certification (a much more rigorous standard than the current exams required to sell investment products), as a minimum competency standard for those who provide financial advice. In fact, the CFP Board found that consumers working with CFP professionals gave higher scores to their advisors on a wide range of competencies (e.g., integrity and technical acumen) than those working with non-CFP advisors. Because ultimately, the purpose of licensing is to reduce information asymmetry – where consumers don’t have the means to assess who is a competent professional or not – and also to provide some assurance to consumers that any and all persons holding out as a “financial advisor” actually have at least the minimum capabilities – training, education, and experience – to deliver those services in a competent manner.

Financial Advisor ‘Quality Guarantees’ Through Fiduciary Accountability

Another method that Akerlof prescribes to increase consumer confidence and reduce the harmful effects of information asymmetry is through quality guarantees.

If the seller guarantees the quality of their good or service, the burden falls on them to ensure they are selling a ‘peach’ rather than a ‘lemon’, because they would be on the hook financially if their product turns out to be defective (whether by having to offer a repair or a refund). Such guarantees can come from the sellers themselves (e.g., car dealers offering warranties on their cars) or through regulation requiring that such guarantees are offered or otherwise forces sellers to be accountable for selling low-quality products or services. In the world of cars, state and national “Lemon Laws” have raised the bar for car sellers, offering consumers remediation if a car they purchase turns out to be defective.

While financial advisors are understandably unable to offer outright performance guarantees (as a client’s portfolio is subject to the whims of the market, among other factors), the implementation of a broad-based fiduciary standard for anyone who holds out as a “financial advisor” or “financial planner” can give consumers more confidence that, if for some reason they don’t choose a good advisor, the advisor will be legally accountable for the consequences. Which increases trust for consumers while reducing the profitability of low-quality sellers (who have to pay up from time to time for their low-quality results) and without harming high-quality providers (who face no such legal exposure because they are already providing a high-quality service).

Similarly, greater transparency regarding costs and benefits can give consumers additional confidence in the quality of service they receive. Such practices could include a clear listing of all fees (so that consumers do not have to worry about ‘hidden’ fees embedded in products), as well as a listing of potential conflicts of interest the advisor might face (so that the consumer does not just know that these conflicts exist, but also what they entail).

And when these disclosures are published in standardized formats (as regulators can require), it can help marketplace participants (e.g., third-party advisor-search services and technology companies developing analytics tools) sift through the information and provide additional insights and guidance to consumers looking for an advisor.

Branding And Truth-In-Advertising Titling

Finally, Akerlof notes that, in trying to combat the adverse effects in the “Market for Lemons”, developing a recognized brand associated with quality can increase consumer confidence.

For example, vehicles made by Toyota often have higher resale values than those made by many other brands because consumers tend to associate Toyotas with quality and durability. On the other hand, the value of used cars from brands associated with lower quality (or those that are new to the market) will tend to depreciate more quickly, as consumers have less confidence that they will have lasting quality.

In the context of financial advisors, few will have the ability to build their own regional or national brand, but the rise of independent RIAs affiliating with third-party custodians (e.g., Schwab and Fidelity) that themselves have recognized and trusted brands in the eyes of consumers can help to confer consumer trust from the affiliated RIA custodian to the independent advisor themselves.

Of course, the secondary challenge with branding – in financial services and, more broadly, in any marketplace with information asymmetries – is that sellers of highly profitable low-quality products often have even more financial wherewithal to market themselves and build their brands as well. Which is why the development of branding must go hand-in-hand with the regulation of how companies are permitted to market.

In most industries, the regulatory approach to branding is, at a minimum, to require a ‘truth-in-advertising’ approach, where products and services must actually do/provide whatever they state that they will. In the context of financial advice, this is currently a challenge, given that there are few regulations governing who can use different titles related to financial advice (e.g., financial advisor or financial planner). Even as many who market themselves as advisors or planners literally aren’t in the business of advice, but in the business of product sales. This has led to calls from a range of industry representatives to ensure that only those who are solely in the business of providing financial advice, rather than in the business of primarily selling products, are permitted to use titles such as “financial advisor” and “financial planner”, and that they adhere to appropriate competence and ethical standards commensurate with their title-promised service. These title ‘brands’ would then give consumers more confidence in the quality of service they would receive from a professional using that title.

The Positive Effects Of High Standards For Financial Advisors

Notably, the United States would not be the first country to significantly raise the standards for providing financial advice. In recent years, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and other countries have implemented regulations to lift standards in the financial advisory industry (typically well beyond the current standards in the US). These regulations have included enhanced educational and expertise requirements, as well as stricter regulations such as outright banning some commissions for advisors and forcing them to charge fees instead.

In the case of the UK (which banned commissions outright), these changes brought improvements for consumers and advisors alike. According to UK Financial Conduct Authority data tracking the impacts of the reforms, between 2017 and 2020, consumers reported increased satisfaction with the financial advice they received (up to 56% from 48%) and increased trust in their advisors to act in their best interest (up to 66% from 58%). The number of formal complaints against advisors also fell from 2,197 to 1,635. Further, contrary to the predictions of some in the financial products industry that higher standards would lead to fewer consumers accessing financial advice, the number of consumers accessing financial advice increased by 33% (from 3 million to 4 million individuals) between 2017 and 2020. In addition, the average revenue per advisor increased by 21%, and the total revenue per firm rose by 37% between 2016 and 2020.

These data points suggest that reforms may not only be good for consumers, but for advisory firms as well! (Or, at least, the ones that are actually in the business of providing high-quality advice!)

Ultimately, the key point is that information asymmetries leading to reduced consumer trust are common in the financial advisory marketplace, and raising industry standards of conduct can serve to improve consumer confidence in advisors, while also reducing the marketing costs for advisors trying to gain consumer trust. These trust-building steps could come in a variety of areas – from advisor competence to title reform – and would likely require regulatory action to implement and enforce.

But in the end, not only does helping consumers differentiate between advisor ‘peaches’ and ‘lemons’ improve their experience with financial advice, but it can also reduce marketing expenses for advisors (and therefore reduce the total cost of advice). At the same time, such efforts can also increase access to advice, helping advisors attract prospective clients from a broader pool of individuals who are willing and able to work with an advisor in the first place!