Xi Jinping will shortly be confirmed for a third term as general secretary of the Communist party and head of the military. So, is his achievement of such unchallengeable power good for China or for the world? No. It is dangerous for both. It would be dangerous even if he had proven himself a ruler of matchless competence. But he has not done so. As it is, the risks are those of ossification at home and increasing friction abroad.

Ten years is always enough. Even a first-rate leader decays after that long in office. One with unchallengeable power tends to decay more quickly. Surrounded by people he has chosen and protective of the legacy he has created, the despot will become increasingly isolated and defensive, even paranoid.

Reform halts. Decision-making slows. Foolish decisions go unchallenged and so remain unchanged. The zero-Covid policy is an example. If one wishes to look outside China, one can see the madness induced by prolonged power in Putin’s Russia. In Mao Zedong, China has its own example. Indeed, Mao was why Deng Xiaoping, a genius of common sense, introduced the system of term limits Xi is now overthrowing.

The advantage of democracies is not that they necessarily choose wise and well-intentioned leaders. Too often they choose the opposite. But these can be opposed without danger and dismissed without bloodshed. In personal despotisms, neither is possible. In institutionalised despotisms, dismissal is conceivable, as Khrushchev discovered. But it is dangerous and the more dominant the leader, the more dangerous it becomes. It is simply realistic to expect the next 10 years of Xi to be worse than the last.

How bad then was his first decade?

In a recent article in China Leadership Monitor, Minxin Pei of Claremont McKenna College judges that Xi has three main goals: personal dominance; revitalisation of the Leninist party-state; and expanding China’s global influence. He has been triumphant on the first; formally successful on the second; and had mixed success on the last. While China is today a recognised superpower, it has also mobilised a powerful coalition of anxious adversaries.

Pei does not include economic reform among Xi’s principal objectives. The evidence suggests this is quite correct. It is not. Notably, reforms that could undermine state-owned enterprises have been avoided. Stricter controls have also been imposed on famous Chinese businessmen, such as Jack Ma.

Above all, deep macroeconomic, microeconomic and environmental difficulties remain largely unaddressed.

All three were summed up in former premier Wen Jiabao’s description of the economy as “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”.

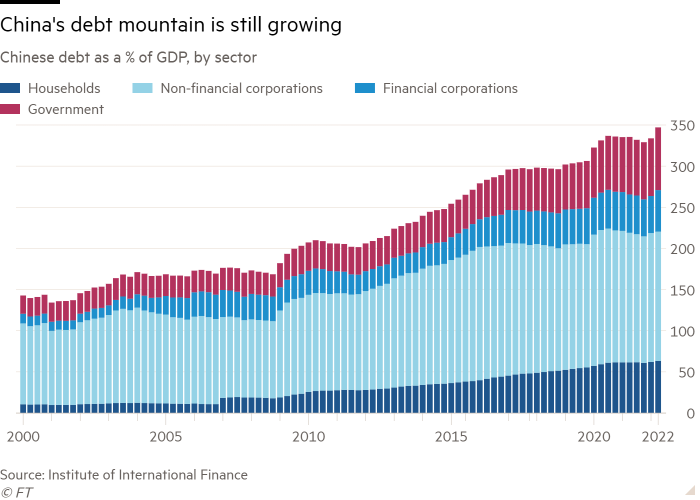

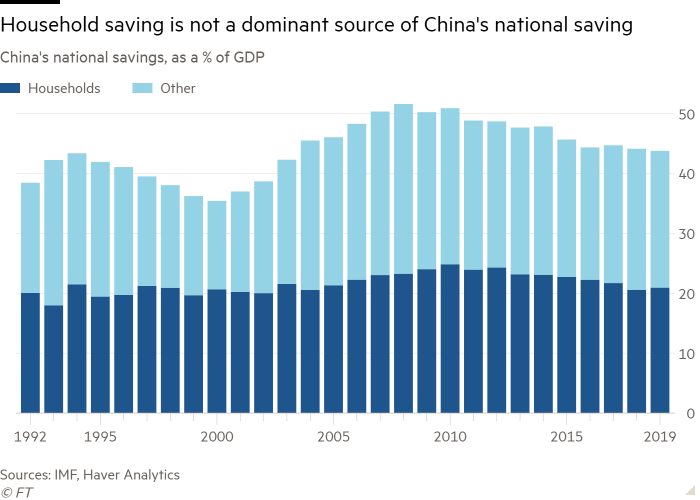

The fundamental macroeconomic problems are excess savings, its concomitant, excess investment, and its corollary, growing mountains of unproductive debt. These three things go together: one cannot be solved without solving the other two. Contrary to widely shared belief, the excess saving is only partly the result of a lack of a social safety net and consequent high household savings. It is as much because household disposable income is such a low share of national income, with much of the rest consisting of profits.

The result is that national savings and investment are both above 40 per cent of gross domestic product. If the investment were not that high, the economy would be in a permanent slump. But, as growth potential has slowed, much of this investment has been in unproductive, debt-financed construction. That is a short-term remedy with the adverse long-term side effects of bad debt and falling return on investment. The solution is not only to reduce household savings, but raise the household share in disposable incomes. Both threaten powerful vested interests and have not happened.

The fundamental microeconomic problems have been pervasive corruption, arbitrary intervention in private business and waste in the public sector. In addition, environmental policy, not least the country’s huge emissions of carbon dioxide, remains an enormous challenge. To his credit, Xi has recognised this issue.

More recently, Xi has adopted the policy of keeping at bay a virus circulating freely in the rest of the world. China should instead have imported the best global vaccines and, after they were administered, reopened the country. This would have been sensible and also indicated continued belief in openness and co-operation.

Xi’s programme of renewed central control is not surprising. It was a natural reaction to the eroding impact of greater freedoms on a political structure that rests on power that is unaccountable, except upwards. Pervasive corruption was the inevitable result. But the price of trying to suppress it is risk aversion and ossification. It is hard to believe that a top-down organisation under one man’s absolute control can rule an ever more sophisticated society of 1.4bn people sanely, let alone effectively.

It is not surprising either that China has become increasingly assertive. Western unwillingness to adjust to China’s rise is clearly a part of the problem. But so has been China’s open hostility to core values the west (and many others) hold dear. Many of us cannot take seriously China’s adherence to the Marxist political ideals that have demonstrably not succeeded in the long run. Yes, Deng’s brilliant eclecticism did work, at least while China was a developing country. But reimposition of the old Leninist orthodoxies on today’s highly complex China must be a dead end at best. At worst, as Xi stays indefinitely in office, it could prove something even more dangerous than that, for China itself and the rest of the world.