By Conor Gallagher

At the beginning of this year there were four pipelines carrying natural gas from Russia to Europe, and a fifth (Nord Stream 2) was about to come online. Now Nord Stream 1 and 2 are dead, the Yamal Pipeline is closed, and the amount of gas flowing through Ukraine is greatly diminished.

That leaves theTurkStream pipeline, which transports natural gas from Russia to Turkey and then onto southeastern Europe, and it’s in the crosshairs.

South Stream Transport B.V., a Netherlands-based subsidiary of Gazprom that operates the Black Sea portion of TurkStream, said the Netherlands withdrew its export license on September 18 amid wider sanctions from the European Union. South Stream Transport applied for a new license but it doesn’t know if it will receive it.

Now South Stream plans to “suspend the execution of all contracts related to the technical support of the gas pipeline, including design, manufacture, assembly, testing, repair, maintenance and training” due to the sanctions.

That means that “no one will be able to carry out repairs if a pipe is damaged, gas leaks, or if a part of the pipeline comes apart due to an earthquake.”

The news comes on the heels of Moscow’s claim that it foiled an attack on TurkStream. And Washington luminaries are now homing in on the pipeline.

MIchael Rubin of the American Enterprise Institute writes that “Biden should kill TurkStream to promote transatlantic energy security.”

Former CIA director and known perjurer John Brennan is very concerned about all pipelines bringing natural gas to Europe:

“Russia will attack other Russian pipelines soon” says John Brennan.

Translation: The US will blow up Turkstream. https://t.co/riSbbyhtg9

— Rosie’s Social Media Madhouse (@DarnelSugarfoo) October 3, 2022

TurkStream was launched in 2020 as part of Russia’s efforts to diversify its export routes away from Ukraine. It has the capacity to deliver 31.5 billion cubic meters of natural gas a year with half of it destined for Turkey and the other half for the Balkans and Central Europe.

Strangely enough, the Blue Stream pipeline that brings gas from Russia to Turkey, but not onto Europe, has yet to come under the same scrutiny as TurkStream.

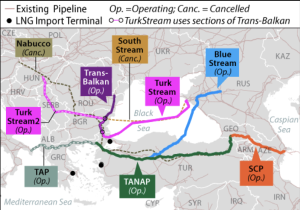

Southeastern Europe Gas Infrastructure. Source: Congressional Research Service

The main European customers of TurkStream natural gas are Serbia and Hungary – the former is an ally of Moscow, and the latter is the most outspoken member of the EU against Russian sanctions.

Other countries, like Austria and Slovakia, also receive gas from TurkStream via Hungary.

Milos Zdravkovic, who heads the department of energy management at Public Enterprise Road of Serbia, told Serbian Monitor that TurkStream would be more difficult to attack than Nord Stream because “it is under Russian and Turkish control, and it is much more difficult to carry out a terrorist attack since this pipeline lies very deep on the seabed.”

Still, countries who rely on TurkStream are recognizing the threat. Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó said on September 28 that increased attention must be paid to the safety of the TurkStream in order to avoid a fate similar to Nord Streams 1 and 2.

Bulgaria just opened a pipeline connector to the Trans-Adriatic pipeline in Greece, which supplies natural gas from Azerbaijan and reduces Sofia’s reliance onTurkStream.

Greece’s biggest gas utility just completed a deal with Total Energies for LNG deliveries in the event gas flows from TurkStream are curbed or halted.

TurkStream came about after the US and EU effectively killed the Russia-Bulgaria South Stream pipeline back in 2014. The project would have transported Russian gas under the Black Sea, making landfall in Bulgaria and then passing through Serbia and Hungary into Austria.

Instead Russia pivoted to Turkey and opened TurkStream at the beginning of 2020 despite US sanctions on companies involved in the construction of the pipeline.

Additionally the US helped kill the EastMed Pipeline which would have brought natural gas from deposits off Israel and Egypt to Greece and elsewhere in Europe via Cyprus. US Undersecretary of State Victoria “F*** the EU” Nuland said at the time that it would take too long and the solution instead was increased LNG shipments to Europe.

Russia supplied about half of Turkey’s natural gas purchases last year, and at an August summit in Sochi Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan vowed to begin gradually paying for Russian imports with rubles.

Doing so would avoid the dollar and would protect the Turkish economy from its diminishing hard currency reserves. The Turkish lira is down approximately 27 percent against the dollar this year.

The loss of TurkStream would have devastating consequences for a Turkish economy already in freefall.

Turkey would be left scrambling for natural gas supplies like the rest of Europe, and it would damage Turkish industry exports, which Erdogan is committed to boosting by lowering borrowing costs. He continues to go against the economic grain by lowering interest rates. In September consumer prices were up annually by 83 percent, and the domestic producer price index was up 152 percent year on year.

Turkey’s deficit was at $4 billion for July bringing it up to $36.6 billion for the year. And the foreign trade deficit was at $10.7 billion in July. The increasing import bill – especially energy – played a large role in the figure.

Without TurkStream, Ankara would also lose undisclosed monthly amounts to the Turkish treasury in transit fees for every cubic meter transferred.

Turkey is now requesting that Russia delay its gas payments until 2024. Any economic boost Erdogan can find could help him next year in what’s shaping up to be his toughest reelection fight yet.

In an effort to improve the economy, Turkey has taken advantage of the Ukraine conflict and continues to pursue a foreign policy of “strategic autonomy.”

Washington, however, is determined to end Turkish economic cooperation with Russia and wouldn’t mind seeing Erdogan replaced next year with a leader who takes their marching orders from NATO.

In August the US Treasury Department threatened secondary sanctions on Turkish financial institutions for processing the Russian Mir payment system.

On September 19 Turkey’s two largest private banks quit accepting Mir; now three state-owned banks are following suit following what the Kremlin called “unprecedented pressure.”

The moves will likely be a blow to Turkey’s tourism industry, which was seeing a major uptick in the number of Russians visiting the country. Turkey, as the only member of NATO not to apply sanctions on Russia, had 2.2 million Russians visit (an increase of 600,000) over the first seven months of 2022.

The US is also abandoning its neutral stance on the longstanding rivalry between Turkey and Greece and funneling weapons to Athens, which is escalating tensions in the eastern Mediterranean.

In September Greece received its first two F-16 military jets from the US as part of a $1.5 billion program to upgrade the Greek fleet. Ankara, which is excluded from the US F-35 program for buying Russian S-400 air defense systems, is worried that in time Greece could have a stronger air force than Turkey.

The US is also ramping up its control over Greece’s Alexandroupolis port in the northeast of the country 18 miles from the Turkish border and using it as an entry point for supplies to Ukraine. From El Pais:

Over the last three years, the United States and Greece have signed agreements to strengthen their defense cooperation and guarantee “unlimited access” to a series of Hellenic military bases. Among these is a Greek Armed Forces installation in Alexandroupolis. Since this collaboration began, the port has experienced unusually high traffic of military ships, so much so that, when 1,500 Marines from the USS Arlington docked in May, the city’s 57,000 inhabitants faced shortages of some products, such as eggs and tobacco.

US military officials have proposed deepening and expanding the port with in order to accomodate US Arleigh Burke-class destroyers.

The US decision to make a fortress out of Alexandroupolis came after Turkey’s decision to close the Turkish straits to all warships after the war in Ukraine began, including its NATO partners who wanted to send weapons to Ukraine via the straits.The move was well within Ankara’s rights under the 1936 Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits, and Turkey’s adherence to the agreement has been credited in not making the Ukraine conflict even worse.

The US pressure on Turkey via Greece doesn’t stop with Alexandroupolis. Turkish drones recorded Greece deploying US-donated armored vehicles on the islands of Lesbos and Samos, which is in violation of international law.

Turkey lodged a protest with the United States and Greece over the deployments, and in a thinly-veiled dig at Washington, Erdogan recently said “we are well aware of the real intentions of those who provoked and unleashed Greek politicians against us.”

Hasan Koni, a scholar on strategic studies at Istanbul Kultur University, told Turkey’s Anadolu Agency the US moves in Greece are meant to send a message to Erdogan:

The American security apparatus has also recognized that the balance of power in the region is shifting toward Turkey and needs to be “checked by empowering Greece,” he said, adding that Washington’s push for more Greek bases is aimed at “containing Turkey.”

Historically, the US played a buffer role between Turkey and Greece and de-escalated tensions. No more.

The same is happening in Cyprus, which is split between the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus in the south and the Turkish Republic of Cyprus in the north, which is recognized only by Ankara.

In September the Biden administration lifted the 35-year-old ban on the sale of US arms to the Republic of Cyprus. Congress restricted the sale of U.S. arms to Cyprus in 1987, hoping it would incentivize a diplomatic settlement to the island’s conflict.

Cyprus was required to block Russian naval vessels from accessing its ports in order to get the US arms sale ban lifted.

Turkey already has about 40,000 troops on the island, and Erdogan recently declared plans to reinforce them with land, naval and aerial weapons, ammunition and vehicles.

Offshore gas fields discovered in the early 2000s further complicated the territorial dispute on Cyprus. The global energy crisis following the West’s war on Russia raised the stakes. And Washington taking advantage of the situation to pressure Turkey adds fuel to the fire.

Cyprus foreign minister Ioannis Kasoulides fears that Cyprus could be dragged into the Turkish-Greek conflict. In a September 26 interview with Bloomberg TV he said, “The Turkish army is stationed on our island and we fear that any conflict in the Aegean Sea will affect us directly because we’ll be used as the weakest link in the whole story.”

Kasoulides must understand all too well the word of Victoria Nuland, who earlier this year at the opening of a US-funded training and cybersecurity facility on the island, said the security relationship between the US and Cyprus is now “irreversible.”