Update to my previous post on the UK treasury imbroglio:

Against the backdrop of an unprecedented [really? Literally never?] repricing [translation: fall in prices] in UK assets, the Bank announced a temporary and targeted intervention on Wednesday 28 September to restore market functioning in long-dated government bonds and reduce risks from contagion to credit conditions for UK households and businesses.

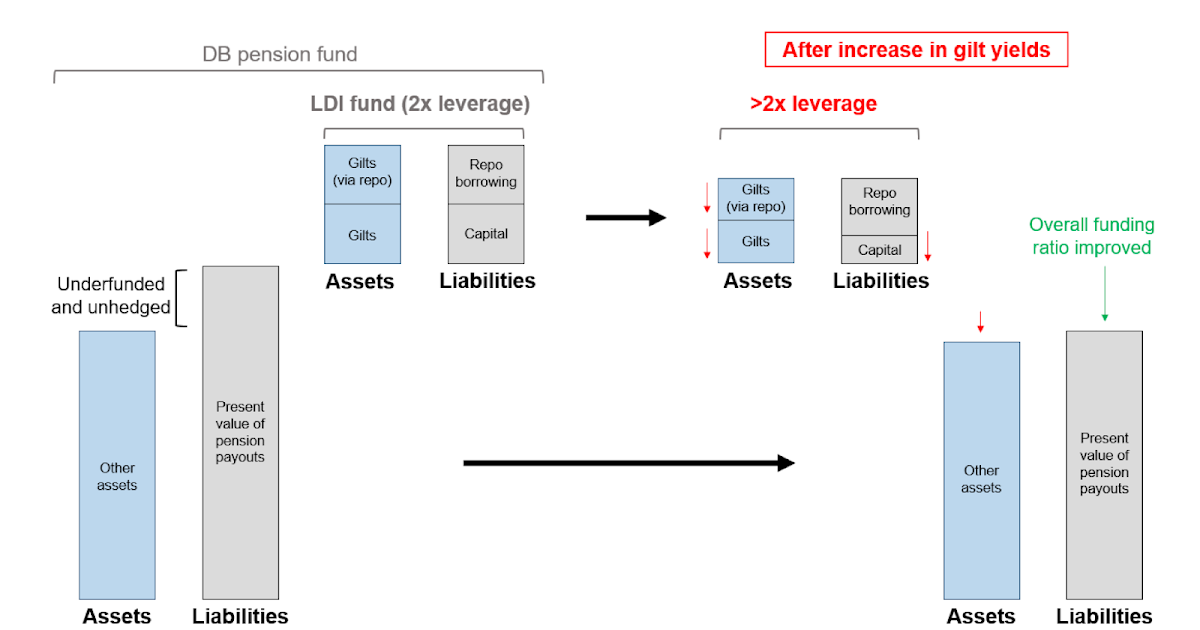

It goes on to a hilarious graph to explain how you lose money when you borrow to lever up a portfolio:

Why is this so funny? Notice on the left hand side a gap between assets and liabilities, yet in the fourth bar there is a positive “capital” bar. Accounting 101, assets = liabilities, including capital. I guess UK regulations operate differently.

But enough fun, let’s get to the point. In answer to my question, roughly “you’re supposed to be this great gargantuan regulator, how could you miss something so simple?,” the bank offers, deep in the report, this:

The FPC has previously identified underlying vulnerabilities in the system of market- based finance, a number of which were exposed in the ‘dash for cash’ episode in March 20202. The Bank and the FPC strongly support and engage with the important programme of domestic and international work to understand and, where necessary, address those vulnerabilities.

The FPC conducted an assessment of the risks from leverage in the non-bank financial system in 2018, and highlighted the need to monitor risks associated with the use of leverage by LDI funds.

Whilst the PRA regulates bank counterparties of LDI funds, the Bank does not directly regulate pension schemes, LDI managers or LDI funds. Pension schemes and LDI managers are regulated by The Pensions Regulator (TPR) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). LDI funds themselves are typically based outside the UK. In this context, given our financial stability mandate, and as stated in the FPC’s November 2018 Financial Stability Report, the Bank has worked with other domestic regulators – including TPR and the FCA – on enhancing monitoring of the risks. That included working with TPR on a survey of DB pension schemes in 2019, and prompting work to improve DB pension liquidity risk management. Given that LDI funds are largely not based in the UK, this also underlines the importance of work on this topic being pursued internationally.

In short, “where is your homework?” “Jimmy was supposed to write up the lab report.” Really, though, if you were working on it, and knew about it, it’s doubly shocking that nobody did anything about it.

… it should also be recognised that the scale and speed of repricing leading up to Wednesday 28 September far exceeded historical moves, and therefore exceeded price moves that are likely to have been part of risk management practices or regulatory stress tests.

The 30 year nominal gilt yield rose by 160 basis points in just a few days, having only had a yield of around 1.2% at the start of the year. On Wednesday 28 September the intraday range of the yield on 30 year gilts of 127 basis points was higher than the annual range for 30 year gilts in all but 4 of the last 27 years. In the 2018 assessment noted above, the FPC assessed the capacity of the biggest derivatives users among UK pension schemes to cover the posting of variation margin calls on OTC interest rate derivatives from up to a 100 basis point instantaneous increases in rates across all maturities and in all currencies. Other tests and risk management practices have similarly assumed a maximum of a 100 basis point move in such a short time period.

In short, once again “it’s a 100 year flood that nobody could have imagined.” The sort of flood that seems to happen about once a year. And 100 basis points is an awfully round number.

There has been significant progress, both domestically and internationally, on the regulation and monitoring of the non-bank sector in recent years. Much of this has been led by the Financial Stability Board, which set out its analysis of risks relating to non- banks and a program of work last year and is due to report on next steps in November. Through the work of the FPC and the Bank more widely, as well as that of the FCA, the UK has been actively engaging with this programme. This episode underlines the necessity of this work leading to effective policy outcomes.

The eternal call for more research.

A last thought. If some people are clearly selling in distress, why are others not buying? Why is your fire sale not my buying opportunity. Well, imagine if every Saturday, when garage sales start at 9 am, the Fed or Bank of England swoops in and buys up all the good stuff at inflated prices. There is then no point in cruising the garage sales any more, and then every time someone wants to sell anything the Fed or Bank of England has to swoop in and buy.

Why do Chase, Citi, Goldman Sachs, or multi-strategy hedge funds not keep some spare balance sheet capacity around to swoop in and buy in these events? Well, knowledge that the Fed and Bank of England will always swoop in first and cut off the profits might well be a part of the answer.

I repeat. The model that financial institutions can lever up, but omniscient regulators will foresee risks, is irretrievably broken. If you need more research on this one, we’ll never get there. We are firmly in the regime of lever to your heart’s content, the Fed and BoE, and thus taxpayers, will offer a free put option on losses. Until, someday soon, they too run out of bailout money.

I should change the tone of this post — let us not blame the BoE and Fed. They are smart, they are human, they are doing their best. It’s just that the best that these great people can do, with 15 years since 2008 to do it, is not enough for this most simple task. And woefully inadequate for the much larger task they have set themselves.