A reader asks:

I know it’s not feasible to consistently time the stock market. But what about the bond market? It’s expected that the Fed will raise rates throughout 2022 and maybe 2023 and then cut them again in the near future (possibly before the elections). Isn’t the following strategy an easy win: buy when rates get “high”, sell when back to 0%? I know those cycles aren’t supposed to be as short as they are now, but I don’t see much attention on this strategy and segment.

The bond market is certainly easier to handicap than the stock market in many ways.

Bonds are governed more by math than the stock market is.

You can try to predict stock market returns using some combination of dividends, earnings, GDP growth or a whole host of other factors but it’s impossible to forecast investor emotions.

And investor emotions, for better or worse, are what set valuations and how much investors are willing to pay for certain levels of dividends, earnings or GDP growth.

For example, earnings grew almost 10% per year in the 1970s but stick market returns were not great. Earnings grew less than 5% per year in the 1980s but returns were fantastic.

Timing the stock market is hard because it’s difficult to predict in the short run and sometimes the long run.

Long-term returns for high-quality bonds are fairly easy to predict because the most important factor is known in advance — the starting yield.

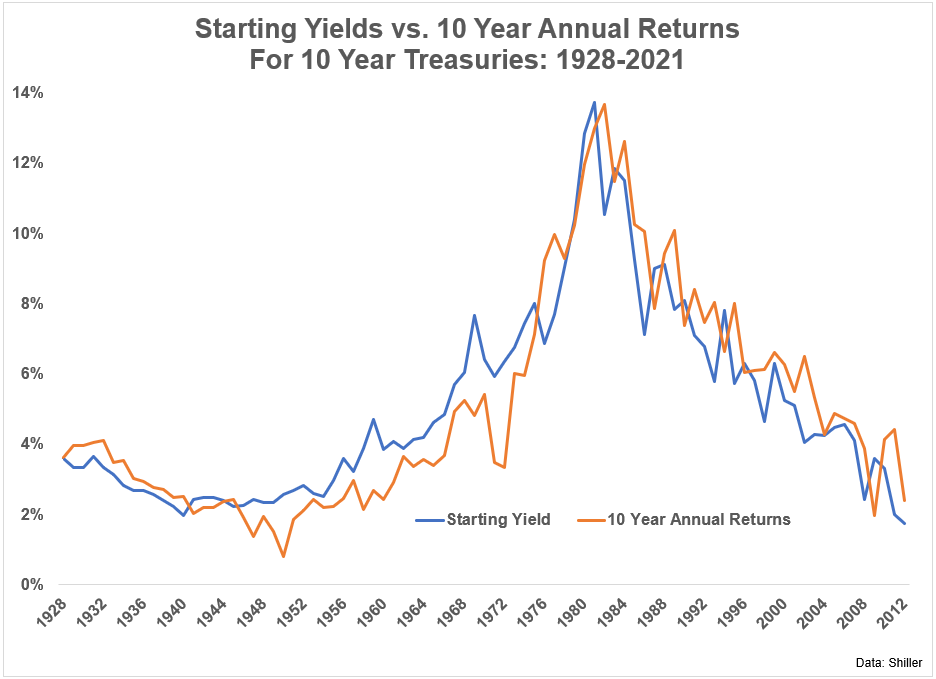

This chart shows the starting yield on 10 year treasury bonds along with the ensuing 10 year annual returns:

That’s a pretty clean chart. The correlation between starting yields and 10 year returns is 0.92, meaning there is a very strong positive correlation here.

If you want to know what your future returns for bonds will be going out 5-10 years into the future, the starting yield will get you pretty darn close.

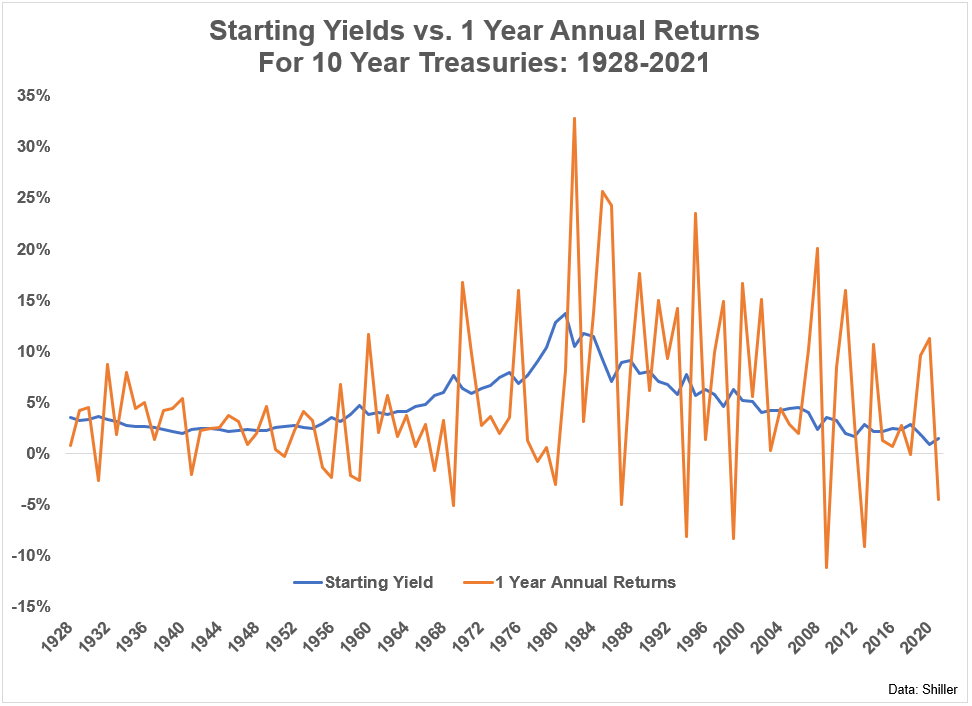

The problem is it’s not all that easy to predict what will happen to bonds in the meantime. Just look at the starting yields versus one year returns over this same time frame:

It’s all over the map because of changes to interest rates, inflation, economic growth and investor preferences.

While long-term returns in bonds are governed by math, the short-term is still governed by emotions and economic uncertainty.

Timing the market is extremely difficult so if you’re going to do it you need some rules in place. The problem is execution will likely be difficult if the bond market doesn’t cooperate with your parameters.

Let’s say you decide to buy bonds when rates hit 5% and sell them when rates go under 1%. This seems like a fairly reasonable model given what’s going on with the market.

That range sounds pretty good right now but what if it’s completely off going forward?

What if the ceiling on yields is much higher than we think right now?

Or what if the floor is higher?

What if 0% is no longer the case for a while during a slowdown?

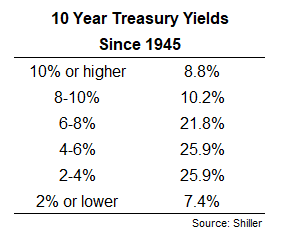

I looked at the distribution of 10 year treasury yields going back to 1945:

Yields have only ben 4% or lower about one-third of the time. It is possible rates are set up to stay much lower for much longer but that’s certainly not guaranteed.

What if rates are stuck in a range from 2% to 6%? Or 3% to 7%?

In that case you end up buying too early and never reach your sell trigger. It does seem possible the Fed will have to bring rates right back down during the next recession but I don’t know what that new level will be.

I do think investors are going to need to be more thoughtful about their fixed income exposure going forward.

In an environment of more volatile interest rates you have to be more considerate when it comes to duration, credit quality and shape of the yield curve when figuring out what it is you want to get out of the bond side of your portfolio.

Every position in your portfolio should have a job and the same is true for fixed income.

Are you looking exclusively for yield?

Do you prefer stability?

Are you in the market for total returns (income + price appreciation)?

It’s more important than ever to define what it is you’re looking for when it comes to bond exposure.

If you prefer to keep the volatility to the stock side of your portfolio, short-term bonds seem like a pretty good deal right now.

If you want to be more tactical it could make sense to take on more duration now that rates are higher and the Fed could push us into a recession.

But it’s important to remember that trying to time the bond market could add even more volatility to your portfolio and not in a good way.

Timing the bond market is probably easier than timing the stock market but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a slam dunk.

It’s much easier to predict the long-term returns on bonds than the short-term returns.

We spoke about this question on the latest edition of Portfolio Rescue:

Michael Batnick joined me as well to discuss questions about municipal bond funds, news vs. uncertainty during bear markets, finding a new job to be closer to family and some thoughts about buying a home in a difficult housing market.

If you have a question for the show, email us: AskTheCompoundShow@gmail.com

Further Reading:

Expected Returns For Bonds Are Finally Attractive