The robust pace of US jobs growth cooled in September but the unemployment rate unexpectedly dropped, firming expectations that the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates by another 0.75 percentage points at its next meeting in November.

The world’s largest economy added 263,000 positions last month, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, fewer than the 315,000 positions created in August and well below July’s 537,000 increase. So far in 2022, monthly jobs growth is averaging 420,000, down from the 562,000 average monthly pace in 2021.

Despite the slower pace of growth, the unemployment rate edged back down to its pre-pandemic low of 3.5 per cent as the share of Americans either employed or seeking a job declined slightly.

“The story is that a 0.75 percentage point hike in November is likely,” said Tiffany Wilding, North America economist at Pimco. “The Fed needs to continue to tighten.”

Officials at the US central bank are actively discussing whether a fourth-consecutive jumbo rate rise is necessary next month or if they can potentially downshift to raising rates in half-point increments. This year, the Fed has lifted its benchmark policy rate from near-zero to a range of 3 per cent to 3.25 per cent.

The debate rests on how resilient the US economy continues to be and whether inflation is beginning to trend back to the Fed’s 2 per cent target.

Friday’s report underscored that the labour market remains quite strong, despite recent signs employers are beginning to scale back hiring.

Traders in fed funds futures contracts on Friday priced in the odds of a 0.75 percentage point rate rise next month at 82 per cent, according to CME Group, up from 75 per cent prior to the latest jobs report.

The S&P 500 closed 2.8 per cent lower on Friday. The yield on the two-year US Treasury, which is sensitive to changes in policy expectations, was up 0.06 percentage points to 4.31 per cent.

According to Alex Veroude, chief investment officer for fixed income at Insight Investment, Friday’s data further solidifies that a Fed “pivot” is not coming anytime soon.

Officials this week have been adamant that they are not yet considering any kind of pause or scaling back of their tightening plans, even as signs of stress begin to emerge in the financial system and the global economic outlook sours. John Williams, president of the New York branch of the Fed, echoed that message on Friday, saying continued price pressures necessitate additional rate increases.

David Kelly, chief global strategist at JPMorgan, implored the Fed not be too “dogmatic” with its policy plans to counter high inflation and to think more about economic forecasts when calibrating its rate rises.

“If you can see a storm on the horizon, don’t just make policy for the weather that you’re experiencing at the moment,” he said.

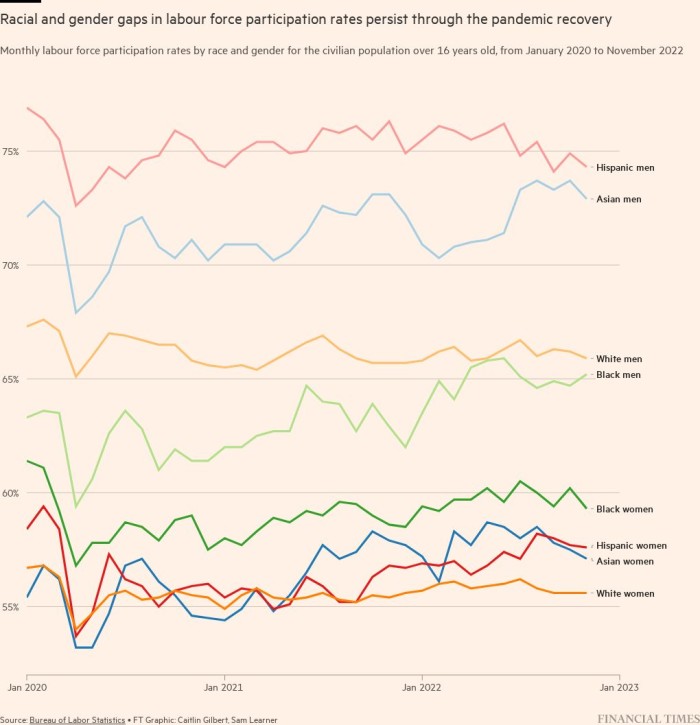

Worryingly, the labour market is still hobbled by a shortage of workers. As of September, the so-called labour force participation rate still remained below its pre-pandemic level, at 62.3 per cent. The overall labour force also shrank by 57,000 people.

Leading the jobs gains was the leisure and hospitality industry, which added 83,000 positions, followed by a 60,000 increase in healthcare employment. The construction and manufacturing sectors continued to add jobs as well, while the number of transportation positions declined.

Average hourly earnings in September increased at the same 0.3 per cent rate as in the previous period, translating to an annual jump of 5 per cent.

The persistently tight labour market — and the wage gains that have followed suit as companies try to attract new hires and retain old ones — is a top concern for the Fed, which is actively trying to restrain demand and reduce price pressures through supersized interest rate increases.

By the end of the year, most officials forecast the federal funds rate to hover between 4.25 per cent and 4.5 per cent, with further rate rises in early 2023. The benchmark policy rate is expected to peak just above 4.5 per cent.

Officials project that their efforts to tame the worst inflation in four decades will require not only a sustained period of “below-trend” growth, but also job losses. A recession cannot be ruled out, Fed chair Jay Powell recently warned.

According to the most recent projections published by the Fed last month, the median forecast among policymakers for the unemployment rate shows it rising to just 3.8 per cent by the end of the year before jumping in 2023 to 4.4 per cent and staying at that level until 2025.

Officials have maintained that inflation can be tamed without a more substantive rise in unemployment, not least because employers may be hesitant to cut their workforces given the magnitude of the labour shortage since the onset of the pandemic.