The Eurozone debt crisis of 2008 to 2012 still affects the European Union today and had implications for the world economy as well. A closer look at the crisis offers insights into ways to prevent the crisis that is currently looming.

What Is the Eurozone?

The Eurozone comprises 19 member states of the European Union (EU) who have adopted the euro (€) as their currency. Croatia will become the 20th member in 2023, and other EU states are legally bound to join once they meet the criteria.

The Euro was officially launched in 1999, bringing the Eurozone into existence.

Causes of the Eurozone Debt Crisis

Entry into the Eurozone provided member states with significant advantages. One of those advantages was a significant reduction in the cost of borrowing for both governments and private entities. This combined with a generally loose global credit environment, with low approval standards and reasonable interest rates, made borrowing extremely attractive in the period from 2002-2008.

The resulting explosion of debt underscored a fundamental problem of the Eurozone. While the zone featured a common currency and a common monetary policy, it included nations with very different policy needs.

The dominant EU economies, like Germany, France, and (at that time) the UK, had a large influence over policy, and the policies that suited them were not necessarily appropriate in the smaller “peripheral states” of the EU.

The strength of the Euro, driven by the strong performance of the core states, quickly left the peripheral states uncompetitive in export markets. Because of the common fiscal policy, they could not revalue their currencies to improve competitiveness. They quickly began showing large trade deficits.

Easy borrowing drove high levels of public and private indebtedness in many countries. Some states, notably Ireland and Spain, saw exorbitant real estate booms as local and foreign buyers took advantage of cheap credit to accumulate assets.

Some of the borrowing was undoubtedly irresponsible. Borrowed money was often not invested wisely. Some went to finance consumption, some government borrowing went to finance arguably unsustainable social assistance policies. Some states resorted to manipulating figures: the government of Greece was forced to admit in 2009 that they had dramatically misstated their debts and budget deficit.

The explosion of debt and the subsequent Eurozone debt crisis are often blamed purely on irresponsible borrowing. It’s important to remember that the very loose lending criteria encouraged aggressive borrowing, and the inability to define nation-specific monetary policies restricted economic development that could have helped nations cope.

The Crisis

In September 2008 Lehman Brothers, a major New York investment bank, filed for bankruptcy. It quickly became evident that their insolvency was the tip of a very large iceberg. An economic bubble supported by enormous amounts of debt quickly deflated, and the contagion spread to Europe.

Iceland – not a member of the Eurozone but a closely linked economy – started the Eurozone debt crisis avalanche. The country’s three largest commercial banks defaulted in quick succession in 2008, forcing nationalization and leaving the country with a debt 7 times its GDP.

By January 2009 a group of 10 Central and Eastern European banks had requested a bailout, and attention was focused on the heavily indebted economies of Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain, a group promptly endowed with the unattractive acronym “PIIGS”. In April 2009 the EU ordered France, Spain, Ireland, and Greece to reduce their budget deficits.

A new government in Greece revealed the nation’s true levels of debt and spurred concern that sovereign defaults were imminent. Greece, Portugal, and Ireland had their sovereign debt downgraded to junk bond status.

Some analysts predicted the collapse of the Eurozone, with the peripheral states leaving the union and returning to their own national currencies.

The Response

It quickly became apparent that large-scale bailouts would be necessary to prevent fiscal collapse in the most indebted Euro countries.

The prospect of bailouts rapidly became a political issue. Taxpayers in the more prosperous northern European countries objected to having to cover what they saw as excessive and irresponsible borrowing in the peripheral states. Citizens in the peripheral states objected to the austerity measures, spending cuts, and tax increases that the EU imposed as a condition for the bailout.

Austerity requirements initially generated strikes and riots in Greece, driving further speculation about an EU breakup.

As the crisis reached the point where it seemed terminal, cooler heads prevailed, EU and International Monetary Fund (IMF) negotiators went to work, and deals started to emerge.

- On May 2, 2010 the EU and the IMF announced a bailout package of EUR 110 billion for Greece.

- In November 2010 it was Ireland’s turn to take a EUR 85 billion bailout.

- If February 2011 EU Finance Ministers announced a 500 billion Euro stabilization fund, called the European Stability Mechanism.

- Portugal received a 78 billion Euro bailout in May 2011.

- Greece received a second bailout of 109 billion Euros in July.

- In August the European Central Bank announced purchases of Spanish and Italian bonds, in an attempt to shore up debt markets.

On Sept. 28, 2011, EU leader Manuel Barroso declared that the EU was facing its “greatest challenge”, amid speculation that negotiations for further bailouts had collapsed.

Facing collapse, European leaders met, help summits, negotiated, and ground out deals. 2012 saw credit downgrades across the continent, more crises, more bailouts, and more political tension, particularly in Greece.

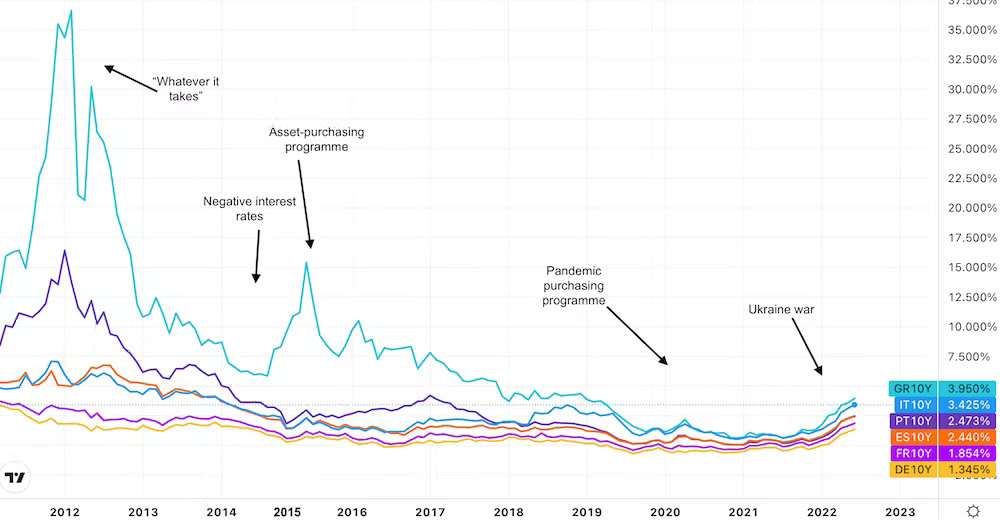

By late 2012, though, there were signs that the crisis was resolving. Government bond yields dropped, indicating improving market confidence that debts would be repaid.

In June 2012 Greece voted for parties that wanted to accept the bailout-related austerity measures, ending speculation that they would leave the EU.

Effects of the Eurozone Debt Crisis

By the end of 2012 fears that the crisis would drive the collapse of the EU had largely receded. The impact of the crisis was felt for years after that point. The debt crisis created a cascade of adverse economic events that extended throughout the continent and beyond.

Economic Contraction

An economic contraction is a stage where the economy as a whole is in decline. This happens after the peak in the business cycle before it becomes a trough.

The Eurozone saw a widespread contraction that affected not only European countries, but also threatened other countries that held European debt or relied on exports to the region.

Job Destruction

Many jobs disappeared, and unemployment became its own crisis. EU unemployment rose, reaching 11.6% by 2014. Governments had to pay unemployment benefits, further stressing their ability to remain solvent.

Internal Conflict

The debt crisis brought lasting stress inside member countries, where the decision to accept painful tax increases and austerity measures created lasting bitterness and internal conflict. The tension between the heavily indebted “peripheral” countries and the EU core remain in place and hamper the EU’s ability to respond to further problems.

High Interest Rates

As countries in the Eurozone became riskier places to loan money, interest rates rose. Investors wanted compensation for their willingness to take on higher risk. Government bonds had to pay higher interest to attract buyers, which threatened governments’ ability to pay interest payments to investors.

A Drop in Currency Value

Currency exchange rates reflect the underlying economy of a country. As the Eurozone economy suffered a decline, so did the value of the Euro. This meant that it was more difficult to pay for foreign debt and imports because more Euros were required.

Note that the euro has not recovered to the level it reached in 2008.

Eurozone’s Current Debt Situation

The Eurozone crisis supposedly ended in 2012, but similar problems are currently worrying European Central Bank policymakers.

Government finances are worse today than at the peak of the previous debt crisis.

For example, Greece’s government debt-to-GDP ratio, which stood at 127% in 2009, ballooned to 211% in 2020. In June of 2022, Italy’s debt amounted to €2.88 billion.

The current trends suggest governments may need to borrow more money in the months or years ahead. After years of some stability, interest rates have skyrocketed many times to multi-annual highs before falling just as abruptly in a few days. In short, interest rates have been volatile.

The COVID health crisis has left a lasting impact on economies. The Russian invasion of Ukrainian territory required the EU to make expensive decisions on defense, sanctions against Russia, taking in refugees, and finding alternatives to Russian energy.

In addition, Europe’s commitment to fighting climate change is costly. Energy, food, and other commodities are rising on all fronts.

As a result, it may be difficult for some EU member states to avoid a recession in the months ahead unless they raise their deficit spending. The fact that no borrowing limit has been in place for several years is a sufficient incentive to continue on the road to growing government debt and spending.

In May 2022, markets calmed down, but there is consensus that Southern European sovereign bonds may have to be discounted. Italy, Greece, and Spain remain exposed to the risk of bankruptcy of sovereign banks.

This negative spiral, through which one country can drag the others down, was central to the previous debt crisis.

Inflation has presented yet another challenge. Economies are slowing, and Eurozone countries are being charged higher rates for loans because there are considered high-risk. The borrowing costs of these nations will inevitably increase. The situation could quickly become difficult because the European Central Bank recently announced that it would tighten its monetary policy to hold inflation at bay. Eurozone inflation hit 8.1 percent, which is much higher than the 2 percent target as of May 2022.

The Latest Developments

As of July 2022, the European Central Bank (ECB) raised interest rates for the first time. This is the first time the ECB has raised rates in more than 11 years. Other increases may follow. Robert Holzmann of the Board of Management has suggested that this should happen this year. Of course, these rate increases will result in higher borrowing costs. Together with lower growth, they could have a negative impact on the viability of sovereign debt.

The ECB will significantly reduce bond purchases throughout 2022. Following a meeting at the beginning of June, the Board of Directors announced a surprise initiative that net purchases under the Asset Purchase Plan would end on July 1, 2022. The central bank will buy 40 percent or less debt in 2022, down from over 120 percent during the COVID peak. The prospect that there could soon be less monetary support for Southern European indebted countries could increase investor wariness.

We can track the Eurozone recovery through bond yields. Bond yields measure the financial community’s perception of a country’s financial stability. The less stable the economy is, the higher the interest they have to pay to get people to but their bonds.

10-year bond yields: Germany = yellow; Greece = turquoise; Italy = blue; Portugal = indigo; France = purple; Spain = orange.

The ECB will buy less than 40 percent of debt in 2022, down from over 120 percent during the COVID peak.

It is unclear what will happen if the ECB stops being a major purchaser of Italian government bonds. How will the country raise the additional hundreds of billions of euros it will need next year to cover its borrowing needs?

This has led to divisions among the institutions of the European Central Bank. In 2019, ECB meetings began to show a geographical divide, Policymakers in Northern Europe supported aggressive tightening of interest rates, while others wanted a more cautious approach. It is challenging to develop a monetary policy that is suitable for very different European economies. In Italy, for example, higher prices give rise to a higher GDP, reducing the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio. In Germany, however, a variety of factors – ranging from high savings rates to the fear of the inflation pace of the 1920s – make inflation a worrisome prospect.

It looks like the EU will find itself either trying to prevent or soften the blows from another Eurozone debt crisis.

However useful the lessons of the past may be, the current situation is fraught with new threats, from climate change costs to worldwide inflation and a possible global recession.