Executive Summary

In the United States, Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) are required to register in one of 2 ways: with the Federal government (namely the SEC) or with one or more state securities regulatory agencies. While SEC-registered RIAs are governed by the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (and its associated regulations), state-registered RIAs are subject to the individual rules of the states (which have their own securities laws and regulations) where they are registered. So RIAs not only face a different set of regulations depending on whether they are Federally or state-registered, but state-registered RIAs, in particular, can also face a widely varying set of rules depending on which state they are registered in.

In this guest post, Chris Stanley, investment management attorney and Founding Principal of Beach Street Legal, breaks down some of the key differences between Federal and state registration, including who needs to register as an RIA, when an RIA can (or must) register with the SEC versus state authorities (including notice filings and unique state circumstances for RIAs with clients in certain states), and registration requirements for RIA firms’ Investment Adviser Representatives (IARs) at the Federal and state levels.

One of the first determinations an RIA owner must make is whether they must register with the SEC or state authorities, and if the latter, which state (or states) they must register with. In general, unless they meet one of a handful of qualifications for an exception (most commonly by having over $100 million in AUM or being registered in 15 or more states), RIAs must register at the state level. State-registered RIAs usually must register in the state(s) where they have a place of business, plus any state where they have more than a ‘de minimis’ number of clients (usually 5) – though notably, Louisiana requires registration from every state-registered RIA with clients in state, regardless of the number, and Texas requires state-registered RIAs to ‘notice file’ if they have less than the de minimis threshold. Several other states additionally require notice filings from SEC-registered advisors with clients in those states, meaning that even for SEC-registered RIAs, staying compliant with filing requirements requires them to understand the filing rules for each state in which the firm does business.

When it comes to the individual IARs employed by advisory firms, the registration requirements also fall along Federal and state lines. State-registered firms generally must have at least one IAR registered in each state where the firm itself is registered, and SEC-registered firms need only register IARs who work with a certain number of clients. The key difference between firm and IAR registration is that, regardless of whether the RIA firm is Federally or state-registered, IARs always register at the state level.

Ultimately, the key point is that the idiosyncrasies between state registration and filing requirements for firms and individuals warrant paying close attention to the rules of each state in which an RIA does business, regardless of whether the firm is Federally or state-registered. This is particularly relevant not only for startup firms but also for those that are expanding or adding clients in new states via new virtual meeting capabilities. By more deeply understanding the nuances of Federal and state filing rules, advisers can be better positioned to stay compliant while managing their changing circumstances!

In the United States, the regulation of investment advisers is intentionally divided between both Federal and state governments. This duality continues the through-line of Federalism borne out of the Constitution, but creates potentially very different experiences for advisers registered with (and therefore regulated by) the SEC as compared to those who register directly with one (or more) state securities authorities. Though while regulatory experiences will differ between SEC-registered advisers and state-registered advisers, there is potentially even more regulatory disparity among the 50 states (plus the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) that impacts state-registered advisers registered in multiple states.

The genesis of such regulatory disparity is helpfully explained on the website of the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA):

States were the first authorities in the United States to regulate securities and the securities industry. Kansas adopted the first securities law in 1911, and other states soon followed. It was not until the 1930s that Congress began enacting federal securities laws. Today, all fifty states, the District of Columbia, and some U.S. territories have securities statutes. These laws, sometimes called “blue sky laws,” have existed alongside the federal securities laws for decades.

Because states adopted their securities acts at different times and with sometimes differing objectives or interests, state securities laws are not all identical. In order to bring a measure of uniformity, the Uniform Law Commission (formerly known as the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws) has, over time, developed model acts that states can use as the basis for their own statutes.

While most states and U.S. territories have adopted various iterations of the Uniform Law Commission’s model securities acts over the years (the current model being the Uniform Securities Act of 2002, known simply as the “2002 Act”), others have largely disregarded such models and created their own securities acts. It is for this reason that advisers registered in multiple states typically shoulder the heaviest burden of regulatory complexity.

On the other hand, SEC-registered advisers (also known as “Federal covered investment advisers” to use the 2002 Act’s parlance) are beholden to the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (the “Advisers Act”) and the rules promulgated thereunder. Notably, RIAs are registered with either the SEC or the states, but never both (although SEC-registered advisers are generally required to ‘notice file’ in applicable states, as discussed later).

Exploring these Federal and state disparities is designed to guide advisers facing registration crossroads for the first time, as well as advisers transitioning from state to SEC registration (or vice versa). While a comprehensive state-by-state analysis has not been undertaken, the 2002 Act (used as the basis for the securities acts of many states) will be used for comparison purposes against the SEC-enforced Advisers Act. Select state-specific nuances will be noted for illustrative purposes as warranted.

Also – just as a reminder – the 2002 Act is simply a model rule and has no legal effect unless otherwise adopted, in whole or in part, by a particular state. Thus, any references to the 2002 Act are for illustrative purposes, and readers should always consult specific state statutes and rules to inform their registration posture.

Federal Vs State Definitions Of “Investment Adviser”

It should not necessarily be assumed that anyone rendering investment advice needs to register as an adviser at all. A person would be required to register at the Federal level (i.e., with the SEC) only if the definition of “investment adviser”, as provided in the Advisers Act, applies to them:

‘Investment adviser’ means any person who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others, either directly or through publications or writings, as to the value of securities or as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities, or who, for compensation and as part of a regular business, issues or promulgates analyses or reports concerning securities […].

The definition goes on to list a series of potential exclusions applicable to banks, certain other professionals that provide such services that are “solely incidental” to the practice of their profession (including brokers or dealers that receive no special compensation for such services), bona fide publishers, those that only render services with respect to very limited types of securities, certain statistical ratings organizations, and family offices.

The 2002 Act, which provides model rules that can be used by state regulators, mostly tracks the Federal definition of ‘investment adviser’, but not in its entirety:

‘Investment adviser’ means a person that, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others, either directly or through publications or writings, as to the value of securities or the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities or that, for compensation and as a part of a regular business, issues or promulgates analyses or reports concerning securities. The term includes a financial planner or other person that, as an integral component of other financially related services, provides investment advice to others for compensation as part of a business or that holds itself out as providing investment advice to others for compensation.

The most notable difference between the two definitions is that the 2002 Act explicitly includes certain financial planners that provide “investment advice” as an integral component of other financially related services. The 2002 Act also additionally excludes investment adviser representatives (since they are separately defined in the 2002 Act as certain individuals employed by or associated with an investment adviser firm) and Federal covered advisers from the state-level “investment adviser” definition.

Assuming a person meets both the state and Federal definitions of “investment adviser,” the next logical question is whether such a person needs to register with the SEC or one or more states.

Federal Vs State Investment Adviser Registration

Because of the divide between Federal and state authority, Section 203A(a) of the Advisers Act (the Federal act) actually prohibits any person from registering at the Federal level (unless they meet certain eligibility criteria):

No investment adviser that is regulated or required to be regulated as an investment adviser in the State in which it maintains its principal office and place of business shall register under [the Advisers Act] unless…

In other words, the Advisers Act relegates adviser registration to the states… unless the adviser is ‘not prohibited’ from registering with the SEC. And only if they meet one of the “exemptions” from the Federal prohibition would they then actually be expected to register Federally with the SEC.

Exemptions That Permit RIAs To Register Under The SEC

The most common exemption from the prohibition against SEC registration is that an adviser has at least $100 million in regulatory assets under management. As a result, investment advisers with less than $100M are prohibited from registering with the SEC (and are state-registered) unless they qualify for another registration prohibition exemption (discussed below), while those that have more than $100M would be expected to register with the SEC instead. Notably, though, in order to qualify, the firm’s AUM must actually meet the regulatory definition of AUM, not merely an ‘Assets Under Advisement’ (AUA) structure.

In addition, there are several other prohibition exemptions that provide a path to SEC registration instead of state registration that can be found in Rule 203A-2 under the Advisers Act or the Advisers Act itself, as listed below. Importantly, each exemption has its own criteria and nuances not described above, so would-be advisers intending to rely on an exemption to pursue Federal registration over state registration should be sure to understand the nuances involved.

- Pension Consultant Exemption: A pension consultant “with respect to assets of plans having an aggregate value of at least $200,000,000” (permitting those who consult with pension plans to be SEC-registered);

- Related-Adviser Exemption: An adviser “controlling, controlled by, or under common control with an adviser registered with the Commission” (permitting subsidiary/affiliate RIAs to be Federally registered as long as their parent/sister company is SEC-registered);

- 120-Day Exemption: “An adviser that, immediately before it registers with the Commission, is not registered or required to be registered with the Commission or a state securities authority of any State and has a reasonable expectation that it would be eligible to register with the Commission within 120 days after the date the investment adviser’s registration with the Commission becomes effective” (e.g., permitting firms that don’t initially have at least $100M because they’re just launching to get to $100M by 120 days to qualify for SEC registration);

- Multi-State Adviser Exemption: “An adviser that, upon submission of its application for registration with the Commission, is required by the laws of 15 or more States to register as an investment adviser with the state securities authority in the respective states” (permitting firms that are required to register in 15 or more different states, but still don’t have more than $100M of AUM, to ‘simplify’ by consolidating into an SEC registration);

- Internet Adviser Exemption: An adviser that “provides investment advice to all of its clients exclusively through an interactive website, except that the adviser may provide investment advice to fewer than 15 clients through other means during the preceding twelve months” (permitting online-only services that may not have individual advisers in individual states to register Federally instead);

- Mutual Fund/Business Development Company (BDC) Adviser Exemption: An adviser to a registered investment company or Business Development Company (BDC);

- Mid-Sized Adviser Exemption: An adviser with regulatory assets under management of at least $25 million, but less than $100 million, that is not subject to examination by the state securities authority of the state where it maintains its principal office and place of business (permitting advisers in that AUM range subject to the unique state laws of New York to qualify for SEC registration); and

- Foreign Adviser Exemption: An adviser with its principal office and place of business outside of the U.S.

In practice, most of these exemptions that would lead to Federal registration do not apply to the typical individual financial adviser that provides personal financial planning advice, though some that expect to quickly launch to more than $100M of AUM may rely on the 120-day exemption (to start with the SEC with $0 in AUM and get to >$100M quickly), and established advisers that have grown a sizable multi-state clientele may trigger the multi-state exemption (though notably, the trigger is not based on having any clients across 15 or more states, but exceeding the de minimis requirements that would require the investment adviser to register in more than 15 states, which is typically a 5-clients-in-that-state threshold).

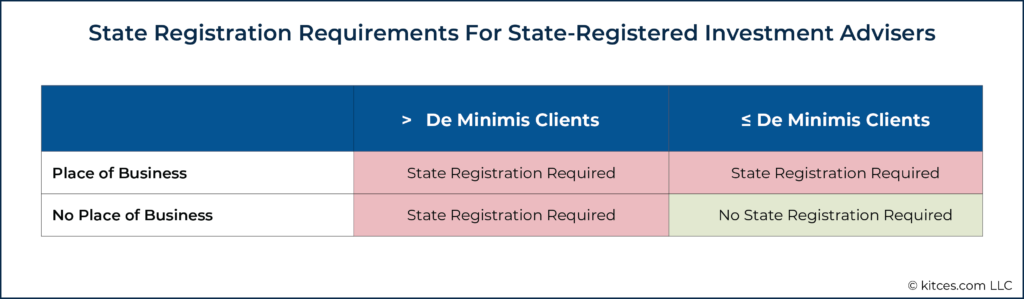

When Advisers Must Register Their RIA At The State Level

Unless an exemption applies that permits SEC registration, a person who otherwise meets the definition of “investment adviser” pursuant to one or more applicable state securities statute(s) will be required to register in such state(s). If this is the case, they will generally be required to register in the state(s) where:

- They have a place of business; or

- They have had more than a de minimis number (typically 5, but lower in a few states) of clients resident in such states during the preceding 12 months (even if the adviser has no place of business in the states in which it has had more than a de minimis number of clients within the preceding 12 months).

The 2002 Act defines “place of business” to include any office from which an adviser regularly provides investment advice or solicits, meets with, or otherwise communicates with clients, or any other location that is held out to the general public as a location at which the adviser provides investment advice or solicits, meets with, or otherwise communicates with customers or clients. This broad definition generally includes a home office from which a person regularly sends email to or receives email from, or otherwise has verbal or videoconference communication with, clients or prospective clients (such that even advisers who work with clients entirely remotely/virtually would still be deemed to have a “place of business” wherever their workspace is from which they conduct their virtual meetings).

A small handful of states (e.g., New York, Florida, and Pennsylvania) may not require registration even if an adviser has a place of business within such state, if they do not otherwise have at least the de minimis number of clients in that state, but advisers should confirm applicable conditions and thresholds before availing themselves of any such exclusion or exemption.

The 2002 Act’s threshold number of clients for purposes of the de minimis threshold is 5, meaning that an adviser can generally work with up to 5 clients during a rolling 12-month period in a particular state in which the adviser maintains no place of business without having to register in that state. However, an adviser availing itself of this de minimis threshold must be approved and registered in a state before crossing the 5-client threshold (i.e., before taking on its 6th client in such state).

The 2002 Act’s de minimis threshold aligns with the national de minimis standard, which can be found in Section 222(d) of the Advisers Act and actually preempts a state from requiring the registration of advisers if they don’t have a place of business within such state and, during the preceding 12-month period, had fewer than 6 clients who are residents of such state:

No law of any State or political subdivision thereof requiring the registration, licensing, or qualification as an investment adviser shall require an investment adviser to register with the securities commissioner of the State (or any agency or officer performing like functions) or to comply with such law (other than any provision thereof prohibiting fraudulent conduct) if the investment adviser—

(1) does not have a place of business located within the State; and

(2) during the preceding 12-month period, has had fewer than six clients who are residents of that State.

The national de minimis standard and corresponding state preemption were incorporated into the Advisers Act in 1997 upon the effectiveness of the National Securities Markets Improvement Act of 1996 (commonly referred to as “NSMIA”), and more specifically, the Investment Advisers Supervision Coordination Act contained therein.

One might justifiably think that this preemption prevents any state from regulating an adviser with no place of business within its borders and fewer than 6 resident clients within the past 12 months, but this is not the case. The Federal preemption only prevents states from requiring the registration of out-of-state advisers with de minimis state-resident clients. It does not prevent states from imposing other regulations upon such advisers, and – as Texas exploits – does not prevent states from imposing a notice filing requirement on such advisers.

When State-Registered Advisers May Need To Notice File In Texas

In general, a “notice filing” is intended to refer to an SEC-registered investment adviser’s obligation to provide applicable state securities authorities copies of documents that are filed with the SEC; this is how the term “notice filing” is defined in the Glossary of Terms to Form ADV. A notice filing is accomplished by simply paying applicable state(s) a notice filing fee and checking applicable state(s’) boxes on Form ADV Part 1. In general, notice filing does not apply to state-registered investment advisers; if they exceed the applicable de minimis threshold, they must register in each applicable state, and only SEC-registered firms are required to notice file (as they’re already registered at the Federal level with the SEC).

However, one state – Texas – has famously appropriated the concept of a notice filing and expanded the term to apply even to state-registered advisers with no place of business within its borders and fewer than 6 resident clients within the past 12 months. Texas extends its extraterritorial jurisdiction to out-of-state, state-registered advisers with de minimis Texas-resident clients (i.e., equal to or less than the 5-client de minimis threshold) by requiring such firms to notice file in Texas if the adviser has but a single client residing in Texas.

A notice filing, as Texas construes the term, effectively requires such advisers to file notice of its Form ADV and at least one individual’s Form U4 in Texas through the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD) and pay an initial and annual notice filing fee. (For reference, Form U4 is the document that associates an individual representative with a particular adviser and registers that individual as an investment adviser representative. Investment adviser representatives are discussed further below, and Form U4 is discussed further in Part 2 of this article.)

As long as the adviser has 5 or fewer Texas-resident clients and does not maintain any place of business in Texas, the adviser will see its “registration status” listed as “Conditional Restricted” with the IARD and its publicly available sister website, the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website. Before contracting with its 6th client or establishing a place of business in Texas, the state-registered adviser must then fully register in Texas (as the 5-client de minimis threshold is reached). To reiterate, a registration is different from (and more onerous than) a notice filing.

Check out the Texas State Securities Board’s FAQs for a helpful explanation, specifically question and answer 1.A.9:

Q: Didn’t NSMIA create a national de minimis exemption from investment adviser registration?

A: Yes. See Section 18a of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. If an investment adviser does not have a place of business (See FAQ 1.A.10) located in Texas and, during the preceding 12 month period, had no more than five clients (See FAQ 1.A.11) who are Texas residents, the investment adviser is not required to register with the Texas Securities Commissioner. See Rule 116.1(b)(2)(A)(iv). However, a notice filing and fee are required. See Rule 116.1(b)(2)(C) and FAQ 1.A.12. This is satisfied by filing Form ADV through the IARD system for the firm as well as filing Form U 4 for each investment adviser representative through the CRD system.

Touché Texas, touché.

When State-Registered Advisers May Need To Register In Louisiana

Similarly, Louisiana does not conform to the national de minimis standard with respect to state-registered investment advisers either, though its regulations flat-out don’t address any de minimis carve-outs like Texas (see Louisiana Securities Law Sections 702 and 703), which makes it unclear how its no-de-minimis registration requirement would be legally enforceable given the Federal preemption afforded by Section 222(d) of the Advisers Act.

Nonetheless, to the extent its statutes have not been legally challenged, Louisiana extends its extraterritorial jurisdiction to out-of-state, state-registered advisers with de minimis Louisiana-resident clients (i.e., equal to or less than the 5-client de minimis threshold) by requiring such firms to register in Louisiana if the adviser has but a single client residing in Louisiana. Setting aside the unique circumvention of the Federal preemption afforded by Section 222(d) of the Advisers Act by Texas and Louisiana, state-registered advisers can otherwise generally expect to register in any state in which they have a place of business or, during the preceding 12-month period, more than a de minimis number of 5 clients in that state.

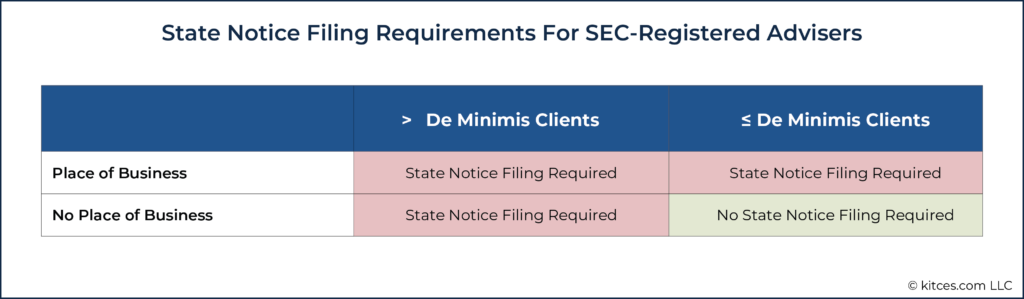

When SEC-Registered Advisers May Need To Notice File In A State

If an adviser is instead eligible or required to register with the SEC and not with any particular state, the states still retain jurisdictional authority insofar as they can require certain SEC-registered advisers to notice file in their state, collect associated state filing fees, and enforce their respective state anti-fraud statutes.

Such notice filing requirements generally apply unless the SEC-registered adviser has no place of business in the state and has had, during the preceding 12 months, no more than 5 clients that are residents in such state. This notice filing place-of-business and client-de-minimis threshold is thus effectively identical to the registration place-of-business and client de minimis threshold described earlier.

In other words, state-registered RIAs typically register in each state in which they have a place of business or where the 5-client de minimis thresholds are reached (with the exceptions of Texas and Louisiana as discussed above), while Federally registered RIAs (that meet an exemption to permit SEC registration, such as being over $100M of AUM) will have registered with the SEC but then notice filed in each state where the firm has a place of business or exceeds the 5-client (or in certain states as discussed below, lower) threshold.

However, once again, there are a handful of states that don’t follow the same notice-filing threshold for SEC-registered advisers, including Texas, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Nebraska.

New Hampshire’s statement with respect to Federal covered advisers is decidedly unambiguous in this regard:

Every federal covered adviser doing business in New Hampshire must file a notice and pay a fee prior to conducting investment adviser business in New Hampshire. There is no “de minimis” exception from the notice filing requirement.

Nebraska’s notice filing requirement, as stated in Nebraska Revised Statute 8-1103(2)(b), simply does not include the 5-or-fewer clients de minimis carve-out:

[…] it shall be unlawful for any federal covered adviser to conduct advisory business in this state unless such person files with the director the documents which are filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, as the director may by rule and regulation or order require, a consent to service of process, and payment of the fee prescribed in subsection (6) of this section prior to acting as a federal covered adviser in this state.

The ultimate takeaway is that regardless of whether an adviser is state-registered or SEC-registered, it should regularly assess the states in which it is deemed to have a place of business and also in which its clients reside. Such an assessment will determine the states in which an adviser is required to register (as a state-registered RIA) or notice file (as an SEC-registered RIA), as applicable.

Federal Vs State Definitions Of “Investment Adviser Representative”

While investment advisers are subject to registration requirements at the Federal or state level, and SEC-registered investment advisers are generally also required to notice file at the state level, individual investment adviser representatives, too, may also be subject to registration obligations depending on their activities and functions. In other words, while advisers often refer to themselves as “RIAs”, in reality, the “investment adviser” is the firm (the entity), while the individual human being advisers who perform certain functions for the RIA are technically “investment adviser representatives” of the firm (i.e., they’re the individuals who represent the RIA entity).

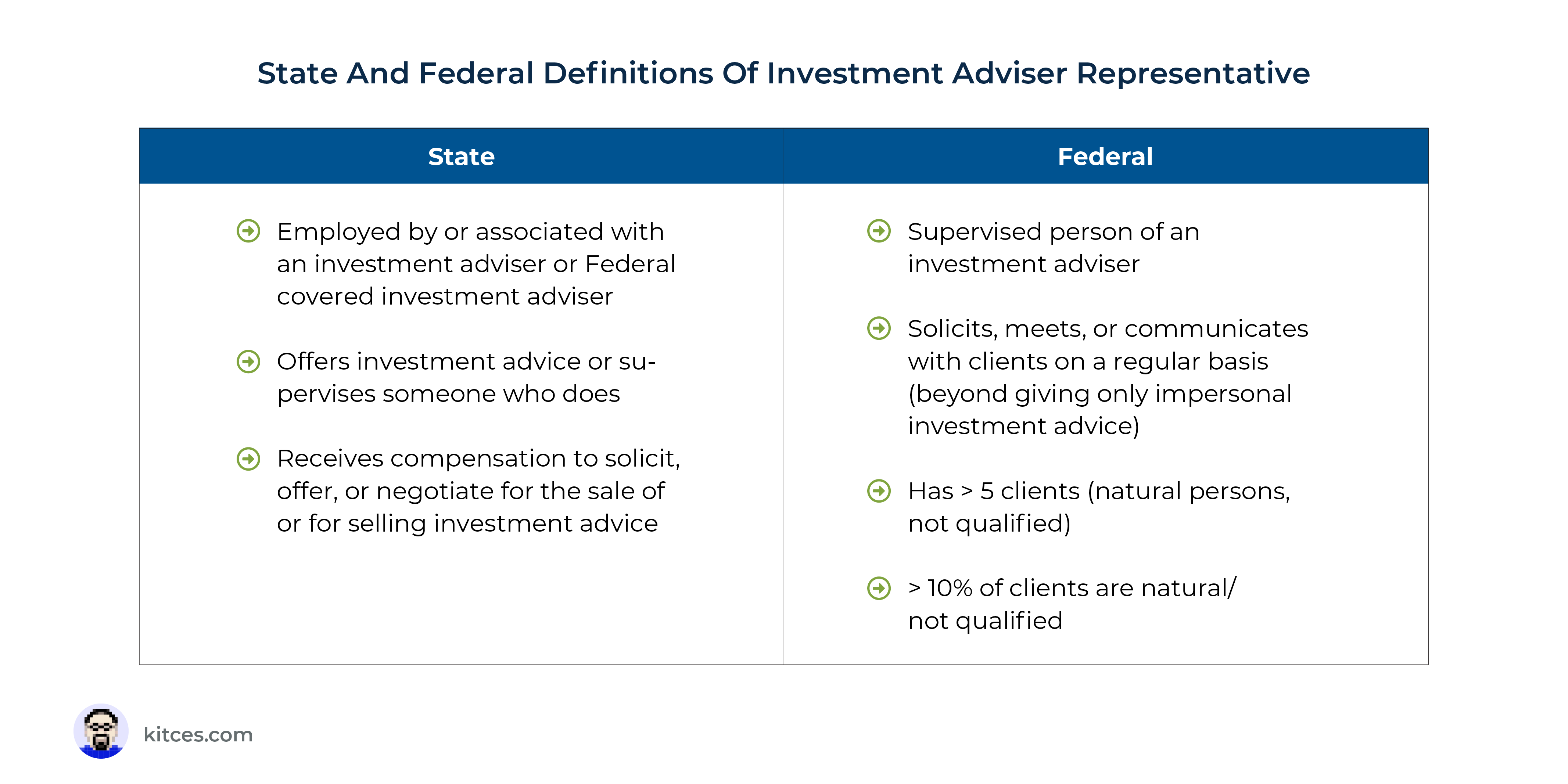

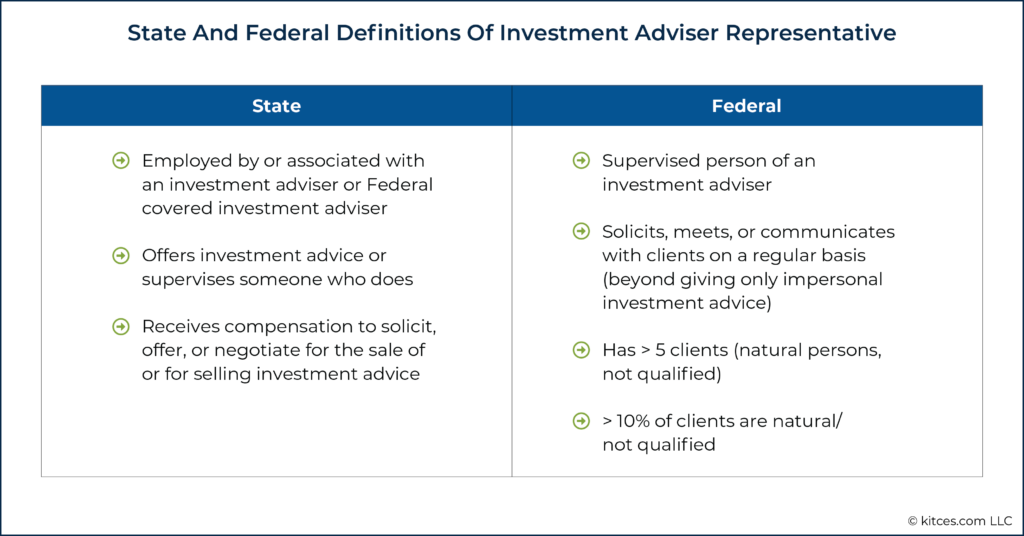

To determine whether an individual representative of an investment adviser is subject to state registration, one must first look to the 2002 Act’s definition of an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR):

An individual employed by or associated with an investment adviser or federal covered investment adviser and who makes any recommendations or otherwise gives investment advice regarding securities, manages accounts or portfolios of clients, determines which recommendation or advice regarding securities should be given, provides investment advice or holds herself or himself out as providing investment advice, receives compensation to solicit, offer, or negotiate for the sale of or for selling investment advice, or supervises employees who perform any of the foregoing.

For state-registered investment advisers, this definition means that an individual associated with or employed by a state RIA will be deemed an IAR if they perform any of the activities or functions described in the definition above and will generally be required to register with applicable states as an IAR.

However, while this may be true for individuals associated with or employed by state-registered investment advisers, the analysis does not end there for individuals associated with or employed by SEC-registered RIA firms. This is because the 2002 Act’s definition of IAR goes on to carve out any individual employed by or associated with an SEC-registered adviser that would otherwise be swept into the 2002 Act’s definition of IAR unless such individual has a “place of business” in a state (as that term is defined in Rule 203A-3(b) under the Advisers Act), and one of the following applies:

- They are an “investment adviser representative” (as that term is defined in Rule 203A-3(a)(1) under the Advisers Act); or

- They are not a “supervised person” (as that term is defined in Section 202(a)(25) of the Advisers Act).

The 2002 Act’s definition of IAR incorporates and cross-references several important Federal definitions found in the Advisers Act and the rules promulgated thereunder regarding IARs and supervised persons. These should be reviewed when assessing potential registration obligations in any state where business is conducted by individuals associated with or employed by SEC-registered advisers:

- “Place of business”, as defined in Rule 203A-3(b) under the Advisers Act (the Federal act), is an office at which the IAR regularly provides investment advisory services, solicits, meets with, or otherwise communicates with clients, and any other location that is held out to the general public as a location at which the IAR provides investment advisory services, solicits, meets with, or otherwise communicates with clients. This definition is effectively identical between the Advisers Act and the 2002 Act.

- “Supervised person” as defined in Section 202(a)(25) of the Advisers Act is any partner, officer, director (or other person occupying a similar status or performing similar functions), or employee of an investment adviser, or other person who provides investment advice on behalf of the investment adviser and is subject to the supervision and control of the investment adviser. The 2002 Act does not separately define the term “supervised person,” so this particular definition only exists in the Advisers Act.

- “Investment adviser representative”, as defined in Rule 203A-3(a)(1) promulgated under the Advisers Act, is a supervised person of an investment adviser who has more than 5 clients who are natural persons and not qualified clients, and more than ten percent of whose clients are natural persons who are not qualified clients (the term “qualified client” can be found in Rule 205-3(d)(1), and generally has a threshold of >$1.1M of AUM and a net worth of >$2.2M; this is the same definition used for purposes of determining eligibility to be charged performance fees). A supervised person does not, however, meet the (Federal) definition of IAR if the supervised person does not, on a regular basis, solicit, meet with, or otherwise communicate with clients, or if they provide only impersonal investment advice.

Notably, the definition of IAR under the Advisers Act is thus much narrower than the definition of IAR under the 2002 Act. To be deemed an IAR under the Advisers Act, and therefore satisfy one of the IAR registration conditions under the 2002 Act, an individual must be both a supervised person and also have more than a threshold number and percentage of clients other than qualified clients.

As a result, at least under the model 2002 Act, an individual associated with an SEC-registered investment adviser that solely works with qualified clients, or works with less than the threshold number or percentage of clients other than qualified clients, is not subject to state IAR registration requirements, even if such an individual has a place of business in a particular state. Similarly, an individual associated with an SEC-registered RIA that works with enough clients to meet the thresholds but does not have a place of business in a particular state is not subject to state IAR registration requirements.

In summary, individuals associated with or employed by both state-registered advisers and SEC-registered advisers must look to the 2002 Act’s definition of IAR, but those associated with or employed by SEC-registered advisers must also look to the Federal definitions of “place of business,” “supervised person,” and “investment adviser representative” to determine whether state IAR registration is required for an adviser working at an SEC-registered RIA.

Federal Vs State Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) Registration

For those who are deemed an Investment Adviser Representative (IAR) by a state (because they have a place of business in that state and meet the applicable state or Federal requirements to be deemed an IAR), registering as an IAR in the applicable state typically requires 3 components:

- Passage of an examination sponsored by NASAA (i.e., the Series 65) or the valid existence of a qualifying professional designation such as the CFA, CFP, ChFC, CIC, or PFS;

- Filing of Form U4; and

- Payment of a fee.

In practice, the exam or the professional designation is what qualifies an individual to register as an IAR in a particular state, while the U4 filing and fee payment are what completes the process to become registered as an IAR under the RIA in the applicable state.

With respect to state-registered advisers, the IAR registration requirement tracks the firm-level RIA registration requirement. In other words, if an RIA entity is required to register in a particular state based on the analysis described in the section above, generally speaking at least one IAR adviser working at that RIA is also required to register in the same state as well. In fact, an RIA’s state registration is generally not effective until at least one IAR’s state registration is effective, and an IAR’s state registration is generally not effective until the RIA’s firm registration is effective; in this sense, investment adviser and IAR state registrations are co-dependent.

Example 1: XYZ Advisors is a state-registered RIA with a single IAR – Bonnie – based in Missouri. XYZ Advisors and Bonnie are both registered solely in Missouri.

Due to the firm’s growth, XYZ Advisors needs to additionally register in Kansas because it has hit the 5-client de minimis maximum in Kansas and is expecting further client growth in the state.

Even though neither the firm nor Bonnie has any place of business in Kansas, both the firm and Bonnie must register in Kansas (as an RIA and IAR, respectively).

With respect to SEC-registered RIAs, the IAR registration requirement is based on the 2002 Act’s definition of IAR when read in conjunction with the Federal definitions of place of business, supervised person, and IAR. As a result, an IAR of an otherwise identically situated RIA may be subject to differing registration requirements if the RIA is SEC-registered instead of state-registered.

Example 2: ABC Advisors is an SEC-registered RIA with a single IAR – Clyde – and is notice-filed only in Missouri because of the firm’s and Clyde’s place of business there.

If the firm experiences the same client growth in Kansas as XYZ Advisors, as in Example 1 above, and hits the 5-client de minimis maximum in Kansas, the firm must notice file in Kansas.

However, unlike Bonnie in Example 1 above, Clyde has no place of business in Kansas, which means that Clyde need not register as an IAR in Kansas.

Furthermore, some states may deviate from the provisions modeled by the 2002 act and impose their own rules. For instance, Texas (of course) does not follow the same IAR registration logic and may still require an IAR associated with an SEC-registered adviser to follow different rules. For example, Texas requires notice filing for IARs who work with any Texas clients – even if they do not have a place of business in Texas. According to the Texas State Securities Board’s FAQs, “An IAR of an SEC-registered investment adviser, having a place of business (See FAQ 1.B.6) in Texas must register and qualify as an investment adviser representative with the Texas Securities Commissioner. An IAR without a place of business in Texas must notice file.”

Ultimately, though, while each state has its own IAR registration regime for the individual advisers who work at state- and SEC-registered RIA firms, the SEC itself does not have IAR registration requirements for individual advisers. Neither the Advisers Act nor the rules promulgated thereunder impose any registration obligations upon individual representatives of investment advisers, regardless of what activities and functions they perform. This is because the Federal regime does not bifurcate or distinguish between investment advisers (the RIA firm) and their representatives (the individual advisers) for registration purposes.

It is for this reason that all IARs are registered with one or more states and not the SEC itself, why the SEC does not require any separate exams or professional designations for individual advisers, why the Series 65 exam is referred to as the NASAA Investment Advisers Law Examination (and not the SEC Investment Advisers Law Examination), and similarly why the Series 66 exam is referred to as the NASAA Uniform Combined State Law Examination (and not the SEC Uniform Combined Federal Law Examination).

Determining In Which State(s) An Individual Must Register

In summary, the following questions must be answered in order to properly identify the state(s) in which an individual should be registered:

Individual Associated with a State-Registered Investment Adviser

- Does the individual meet the 2002 Act’s definition of IAR?

- In what state(s) is the investment adviser required to register because they have a place of business and/or meet the client de minimis threshold?

- Is the investment adviser required to notice file in Texas?

Individual Associated with an SEC-Registered Investment Adviser

- Does the individual meet the 2002 Act definition of IAR?

- Does the individual meet the Advisers Act definition of IAR or supervised person?

- How many clients does the individual work with, and how many are qualified clients?

- In what state(s) does the individual have a place of business?

- Does the individual work with any Texas clients?

Once an adviser has determined whether it must register with the SEC or one or more states, the specific state(s) in which it is required to register or notice file, and the specific state(s) in which its individuals are required to register or notice file, the adviser can next transition to the actual registration application process itself.

Ultimately, the key point is that there are significant differences between Federal and state-level registration requirements for investment advisers, and even more nuanced differences between how (and if) individuals associated with SEC- and state-registered investment advisers must register.

While beyond the scope of this discussion, it is important to recognize that the registration application process and the post-application regulatory experience can vary dramatically between advisers registering with the SEC and one or more states, as well as among state-registered advisers registered in multiple states. But by understanding the differences in how these terms are defined, and the unique registration (and state notice filing) rules that may apply to them, advisers can be better positioned to maintain their compliance requirements based on their changing individual circumstances!