Executive Summary

Taxes are a central component of financial planning. Almost every financial planning issue – whether it is retirement, investments, cash flow, insurance, or estate planning – has tax considerations, and advisors provide a great deal of value in helping clients minimize their overall tax burden. And yet, despite the prominent role of taxes in financial planning, advisors are often prohibited by their compliance departments from making recommendations for a specific course of action on a certain tax strategy. Which means that advisors are often left to figure out on their own how to guide their clients on tax-related matters without crossing the line into ‘Tax Advice’, which can potentially create certain liability issues for the advisor and their firm.

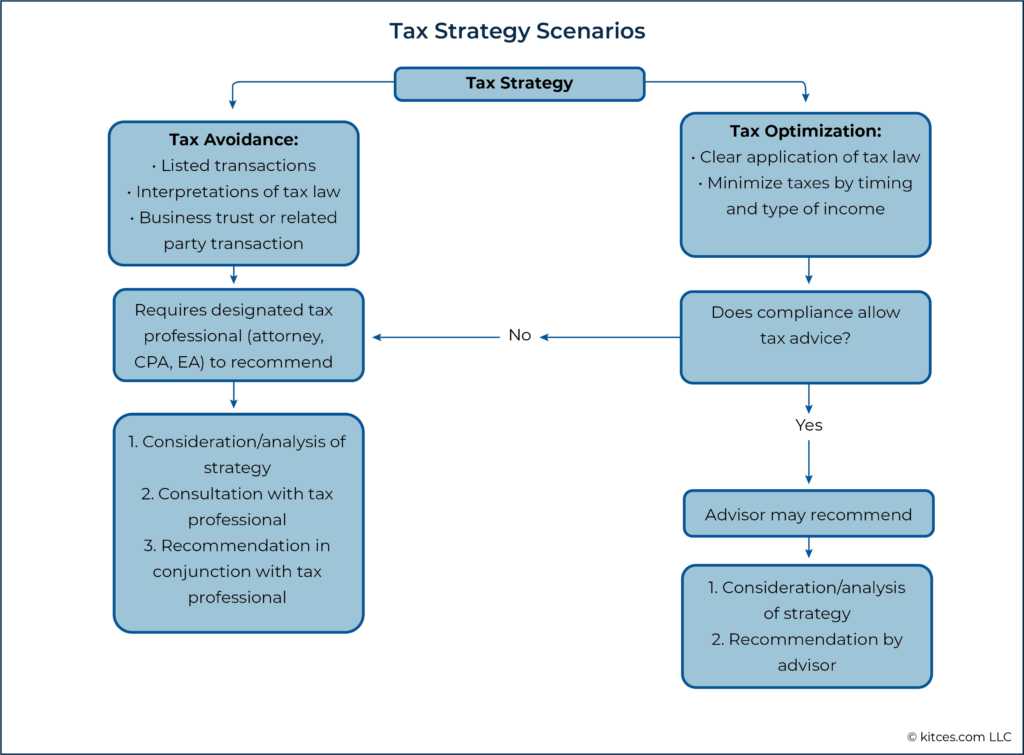

This is not because of any blanket regulation against financial advisors making tax recommendations. Although the IRS states that only designated tax professionals like attorneys, CPAs, and EAs can give advice on certain strategies (e.g., those that are designed to avoid taxation, such as tax shelters, that have a high potential for abusing tax laws), many of the tax strategies that financial advisors recommend are not meant to shelter income to avoid taxation altogether, but are instead designed to ensure that income is simply taxed more efficiently, such as by optimizing the timing or nature of income when it is taxed (e.g., Roth conversion strategies involve recognizing taxable income via the conversion to ensure funds are taxed at the lowest possible rate). From the IRS’s perspective, there is no requirement to be a designated tax professional in order to give advice on such strategies that optimize taxation.

For many advisors, engaging in tax advice is often prohibited because of the potential legal and financial liabilities that are opened up for advisors and their firms. Unlike investment advice, advisory firms are usually not required to create policies and procedures around properly given tax advice (unless they specifically employ designated tax practitioners), so there is often no clear-cut way to ensure tax advice is given correctly. And the consequences for incorrect tax advice can include legal and financial penalties if a client were to be harmed by the wrong advice – which is often not covered by the firm’s E&O insurance –creating an expensive liability when tax advice goes wrong.

For advisors who are prohibited from giving tax advice, tax planning can be an alternative approach for discussing tax matters with clients. Tax planning can range from giving general, nonspecific information on tax laws and regulations to creating detailed projections for clients and comparing the outcomes of potential tax strategies – so long as the planning does not also include a recommendation of a specific course of action that would constitute tax advice. Generally, the more detailed the analysis, the likelier it could be construed by the client as a recommendation – which is what ultimately matters, since a presentation that the client understands to be tax advice is as good as actually giving tax advice. In these circumstances, safeguards such as upfront disclosures and collaboration with the client’s tax professional may be necessary to ensure that the tax professional – and not the advisor – is the one making the actual recommendation.

The key point is that understanding what constitutes tax advice versus tax planning that doesn’t go so far as to make a recommendation can help advisors more confidently engage with their clients on tax matters without violating the unique rules set in place by their compliance departments. Having a framework for the types of advice to give and for the language to use when communicating strategies to clients can reduce the confusion of being obliged to provide guidance on taxes while being prohibited from giving actual tax advice. Because ultimately, the question around tax planning (if not outright advice) isn’t whether it should be offered, but how it can be delivered to provide the most value to clients while protecting the client, advisor, and firm!

Let’s get this out of the way first: Financial advisors give tax advice. They do it all the time. Even when their emails and financial planning materials are fully furnished with disclaimers like “Not intended as tax advice” and “Consult your tax professional”, the truth is that when financial advisors give recommendations that are primarily about reducing their clients’ overall tax burden, this, for real-world purposes, is tax advice.

A partial (but by no means complete) list of the types of tax advice that many financial advisors give includes:

In fact, it’s hard to think of a financial planning topic that doesn’t have any tax implications. Budgeting? Affects how much can be saved to pre- and after-tax accounts! Property and casualty insurance? Reduces the tax basis of an asset if an insurance claim is paid on it! Credit card rewards? Might be a source of tax-free income (unless the IRS says otherwise)! And some of the biggest decisions that a client can make, like when (and where) to retire and when they should claim Social Security benefits, can be driven in large part by the tax considerations involved.

But despite how intertwined taxes are with financial planning, financial advisors are frequently told by their (generally well-intentioned) compliance departments that they need to avoid giving tax advice. Not because there’s anything wrong or illegal about giving recommendations on tax-related subjects – on the contrary, tax recommendations can be an important part of how advisors bring value to their clients. Rather, what makes compliance departments nervous is the legal and financial liability that their firms could be exposed to if a client follows a piece of tax advice given by the advisor and ends up unhappy with the result.

This leaves advisors with a two-sided dilemma: On one hand, they want to create as much value for their clients as possible, with taxes being one of the most important areas that they can bring about that value given the hard-dollar cash savings that can be created. But on the other hand, straying too far into the realm of tax advice could introduce additional legal liability for the advisor in the event that their recommendation turns out poorly – not to mention potentially creating trouble with their firm’s compliance department (whose job is to protect the firm from its advisors creating such liability exposure).

What makes things even more confusing is that, while there are certain types of tax advice that are widely considered acceptable (e.g., advising on traditional versus Roth IRA contributions), and other types that are clearly beyond the pale of the traditional financial advisor (e.g., providing recommendations on how to structure a merger of corporate entities) there is no bright red line that separates one from the other, and no concrete definition that distinguishes a relatively benign tax recommendation from one that creates unacceptable liabilities and would be impermissible from a compliance standpoint.

As a result, firms – and lacking a clear firmwide policy, individual advisors – are left to suss out what it means to safely give ‘tax advice’ (which is good and helps maximize their clients’ wealth) without crossing the line into ‘Tax Advice’ (which is bad and creates legal and/or financial liability for the advisor and the firm that employs them). And while it’s hard enough to walk on the cliff’s edge between giving (good) tax advice and (bad) Tax Advice, in many cases – given the uncertainty of the distinction between the two – it may be impossible to see where the edge of the cliff even is.

Why does this matter? Because in spite of the fact that nearly every advisor is already giving tax advice in one form or another, the ambiguous way that the term has come to be used often steers advisors away from engaging with their clients in meaningful conversations around taxes. There is a clear need for a better framework for communicating tax strategies to clients while remaining compliant with Federal and state regulations and minimizing the risks of legal liability for advisors and their firms.

With such a framework, advisors can be more confident in advising their clients about tax strategy. This is especially the case for advisors who are not already designated tax professionals like CPAs, attorneys, and EAs (who have their own specific requirements around tax advice to comply with as laid out in Treasury Department Circular 230). However, any advisor who works with clients on tax-related matters can benefit from a deeper understanding of what does and doesn’t constitute formal ‘Tax Advice’, and how to communicate tax-related recommendations while protecting both themselves and their clients.

When Tax Advice Is Restricted To Designated Tax Professionals

While there is no single regulation that defines what kinds of tax advice are and aren’t allowed to be given by financial advisors, there are some regulatory publications and areas of the Internal Revenue Code that can be highlighted to create a broad outline of the outer limits of what might be permissible.

First, it is helpful to know what kinds of advice financial advisors definitely cannot give. Because although there is no blanket law or regulation that forbids financial advisors from giving any tax advice if they aren’t registered tax practitioners like CPAs, EAs, or attorneys, there may be certain types of advice that could get an advisor in trouble if they don’t hold these credentials.

How The IRS Regulates Tax Advice

The main document governing how tax advice is delivered to the public is Treasury Department Circular 230, “Regulations Governing Practice before the Internal Revenue Service”. Most of the document is devoted to laying out the duties and restrictions of designated tax practitioners (CPAs, EAs, attorneys, and others in limited circumstances) when practicing before the IRS. But in Sec. 10.2, it also defines what it actually means to “practice” before the IRS, as follows:

Practice before the Internal Revenue Service comprehends all matters connected with a presentation to the Internal Revenue Service or any of its officers or employees relating to a taxpayer’s rights, privileges, or liabilities under laws or regulations administered by the Internal Revenue Service. Such presentations include, but are not limited to, preparing documents; filing documents; corresponding and communicating with the Internal Revenue Service; rendering written advice with respect to any entity, transaction, plan or arrangement, or other plan or arrangement having a potential for tax avoidance or evasion; and representing a client at conferences, hearings, and meetings. [emphasis added]

Notably, the bulk of what is covered – for which one must be a designated tax practitioner in the eyes of the IRS, such as an attorney, CPA, Enrolled Agent, or (in certain limited cases) Enrolled Actuary or Enrolled Retirement Plan Agent – regards actually interacting with the IRS on behalf of a client (e.g., preparing and filing tax documents, corresponding with the IRS, etc.). However, as the emphasized part of the above-quoted section specifies, an individual would also be considered to practice before the IRS – and therefore be required to hold a specific tax designation – if they provided written advice that results in tax avoidance.

By one reading, it would seem very hard to give any type of tax-related recommendation to a client without crossing the line into ‘Tax Advice’, given that the point of most tax strategies is to (legally) minimize the amount of taxes paid by an individual… which is also the generally agreed-upon definition of ‘tax avoidance’. (Tax evasion is, by definition, illegal and would cause trouble for obvious reasons.)

So if any “plan or arrangement having a potential for tax avoidance” constitutes practice before the IRS, does that mean any recommendation of a strategy intended to minimize taxes (which is, again, the goal of almost every tax planning strategy) can only be made by a designated tax professional?

To address this question, it’s helpful to explore what the IRS has historically been more likely to scrutinize as a “plan or arrangement having a potential for tax avoidance or evasion”.

Tax Avoidance Vs Tax Optimization

Tax avoidance strategies that tend to draw the IRS’s scrutiny often involve tax shelters or certain types of transactions that aim to permanently shield income from being taxed (e.g., by routing income through a foreign or tax-exempt entity which results in it not being taxed).

These strategies might be legal by the letter of the law but often are designed to use gray areas and loopholes to stretch the rules – often beyond the intentions of those who created them. The IRS keeps lists of such strategies (literally known as “Listed Transactions”), requires tax advisors who recommend them to file disclosures, and imposes penalties on those who use them abusively.

It’s easy to imagine that the IRS would want to restrict these types of especially controversial tax avoidance recommendations to designated tax practitioners, both because of the complex nature (and legal murkiness) of the strategies involved, as well as the desire to keep track of who is promoting or recommending them.

However, in contrast to these types of tax avoidance recommendations, the overwhelming majority of the tax planning strategies offered by financial advisors are designed not to avoid taxes entirely, but rather to ensure that income is taxed more efficiently. They seek to minimize taxes not by permanently sheltering income but by optimizing the timing or nature of income when it is taxed.

These types of strategies put into practice the notion, as stated in the IRS’s Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights, that everyone has the right to pay no more in tax than is legally owed. In other words, rather than seeking tax avoidance, they aim for tax optimization.

Example 1: Rosie is an advisor who recommends that her client Benny convert pre-tax assets into a Roth account.

Though this recommendation is clearly intended to reduce Benny’s overall taxes, it isn’t a strategy to avoid taxes. That’s because, far from sheltering income from taxation, this strategy involves recognizing taxable income via the Roth conversion and subjecting it to income tax… with the expectation that those dollars will be taxed at a lower rate in the year of the conversion than they would be in the future.

Rosie’s recommendation may qualify as tax advice in the general sense, but because it is intended to optimize rather than avoid taxes, it is not likely to be considered the type of advice that would require a designated tax practitioner to recommend.

In addition to strategies like Roth conversions that optimize the timing of income (i.e., to recognize the income when it will be taxed at the lowest marginal rate), other common tax optimization strategies optimize the nature of income such that each type of income is properly taxed in the way that will result in the lowest possible tax burden for the client.

Example 2: Sam is an advisor who recommends his clients hold taxable bonds in a traditional IRA (where the interest they earn will remain tax-deferred) and municipal bonds are held in a taxable account (where their interest will be exempt from Federal income tax).

With this asset location strategy, no tax is really being avoided here; the income from both types of bonds is being properly taxed according to the laws and regulations regarding their respective account types. The strategy just ensures that the tax characteristics of the bonds align with the rules for each account type in a way that is optimal for the investor.

Aside from the fact that they seek to optimize, rather than avoid, taxes, the key difference between the tax strategies described above (that financial advisors recommend frequently) and the tax shelters that are more heavily scrutinized by the IRS (which must be advised upon by a designated tax practitioner) is that with the former, their legality can be clearly determined by a plain reading of the Internal Revenue Code, whereas in the case of the latter, many tax shelters rely on more creative interpretations of laws and regulations.

Tax Advice Rule 1 For Advisors: Avoid New Interpretations Of Tax Rules

If there is a bright line that financial advisors should avoid crossing, it is recommending any strategy that involves interpreting tax rules in some new or different way rather than simply helping clients understand how to apply existing tax rules in the best way for their own situation. Interpretation should definitely be left to attorneys and CPAs or at least done in collaboration with those professionals.

Examples of tax advice involving the interpretation of tax rules could include:

- Applying existing tax rules in new ways. A prime example of this is backdoor Roth contributions. This planning opportunity was essentially created by accident when the Tax Increase Prevention and Reconciliation Act (TIPRA) of 2005 eliminated income restrictions on Roth conversions, effectively allowing individuals to indirectly contribute to a Roth when their income is too high to do so directly. Though fully legal by the letter of the law, the IRS has never officially acknowledged or sanctioned it. While it has since become widespread, when this strategy was first introduced, it would have likely been considered interpretive tax advice until it eventually became common practice.

- Making recommendations in areas that do not have clear rules. As this article is being written, final regulations have yet to be released regarding provisions of the original SECURE Act, which became law in 2019 – namely, whether or not non-eligible designated beneficiaries must take annual Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) from inherited IRAs. Proposed regulations released in February 2022 stated that annual RMDs would be required, but further guidance issued in October 2022 stated that RMDs would not be required any earlier than 2023. Until the final regulations are issued, giving a definitive answer on the course of action a taxpayer should take would be considered tax advice.

Another example of how this comes up involves whether gold can be held within an IRA. While technically, gold can be owned inside an IRA, the account holder taking physical possession of the gold creates issues because of ambiguity in the rules, and advising clients to do so would be tax advice.

- Opining on pending or proposed tax rules. As this article was written, the SECURE Act 2.0 is still awaiting passage, which means that its provisions – such as moving back the RMD age to age 73 and eventually until age 75 – are purely speculative at this point. Tax advice on this topic might sound like, “and Mrs. Client, even though you both turned 72 this year, I don’t think you will have to take RMDs on your retirement accounts because SECURE 2.0 will be changing the RMD age to 73, so it would make more sense to wait until next year to start taking distributions”.

A more acceptable way to discuss this topic with clients without giving tax advice, however, would sound like this: “Mr. and Mrs. Client, the IRS has not finalized the rules around whether RMDs will be required on your retirement accounts at age 72; if they are required, the RMD would be due by December 31st, so I suggest we wait until later in the year to make a decision”.

These areas can be challenging for advisors who want to push the envelope on tax strategy but are limited by constraints on not giving interpretative tax advice. If advisors must wait until they receive clarity from the IRS to recommend any strategy, clients could miss out on strategies that could potentially be very valuable.

Take the case of backdoor Roth conversions above: if forward-thinking advisors were to have waited for the IRS to officially sanction the strategy before recommending it, backdoor Roth conversions might never have become commonplace enough for more conservative advisors to begin recommending them to their own clients.

In other words, which comes first, the chicken or the egg? If advisors don’t recommend a strategy until it is commonplace… then how does it become commonplace to begin with?

This is where it is important for advisors who want to be on the leading edge of tax planning to be plugged into tax programs to hear what is being talked about and to be connected with CPAs and other tax professionals for their opinions on new rules to see how they apply. Then, advisors – in coordination with the client’s CPA, who takes on the legal liability for new interpretations of tax rules – can clearly educate the client on how the rules might apply to them and the potential benefits (and risks) of any strategies that might follow.

Tax Advice Rule 2: Avoid Recommending Strategies Involving Businesses, Trusts, Or Related Parties

In addition to tax strategies involving ‘loose’ interpretations of the Internal Revenue Code, other strategies that the IRS is more likely to scrutinize (where providing direction to clients about how to structure such arrangements may constitute Tax Advice) can involve setting up or using taxpayer-owned separate entities (e.g., businesses, trusts, or nonprofit entities) and making transactions with relatives or business partners that are structured to avoid income being recognized. This can include the creation of many types of entities that are frequently used for estate planning purposes.

One such example is a Family Limited Partnership (FLP). An FLP is a legal entity that is commonly used for intergenerational wealth transfer. These typically work by having one individual transfer assets, such as securities and/or real estate, to the FLP, receiving a small General Partnership (LP) interest and a large Limited Partnership (LP) interest in return. Next, they would gift portions of their LP interests to one or more family members, which allows those family members to take control of the FLP’s assets after the original partner’s death. And while the gift of an LP interest is subject to gift and estate tax, the restrictions placed on the LP interest – typically including a lack of control over how the FLP assets are managed or distributed and a lack of a secondary market on which the LP interest could be sold – means that the value of the LP interest that is subject to gift and estate tax can be (and often is) claimed at a substantial discount (30% or more) to the actual value of the FLP’s assets.

The IRS often scrutinizes the valuation discounts claimed by those gifting or bequeathing FLP interests. In an arms’-length transaction between neutral market participants, it would be reasonable to expect a discount for the lack of control or marketability afforded by an LP interest; however, when the entire partnership is controlled by members of a single family, it is more difficult to argue that each LP is not receiving the full economic value of the FLP’s assets, thus subjecting the entirety of the LP interests to gift and estate tax – especially when the FLP’s assets consist of marketable securities which could be easily liquidated if agreed upon by the family at any time.

The combination of all three components – a business entity (which requires precise drafting and knowledge of state laws to set up correctly), the gifting of business interests to relatives (which often allows the gifter some degree of control over the gifted assets that isn’t possible with a neutral third party), and a valuation discount that is highly subjective and dependent on detailed analysis – makes FLPs dangerous territory for advisors who aren’t tax practitioners with specific FLP expertise. And the frequency with which FLP cases turn up in tax court means there is a high degree of risk for advisors who recommend an inappropriately high valuation discount to have their recommendation successfully challenged – and then be liable for additional taxes and penalties owed by the client as a result of the recommendation.

The main point, however, is that a complex strategy such as an FLP involves setting up a new entity specifically designed to avoid taxation (in this case, avoiding the gift and estate taxes that would have been owed by simply gifting or bequeathing assets directly to the taxpayer’s heirs). It would be hard to argue that this does not fall within the realm of “rendering written advice with respect to any entity…plan or arrangement having a potential for tax avoidance”, as Circular 230 includes in its definition of practicing before the IRS.

Guidelines To Determine When Tax Advice May Be ‘Practice Before The IRS’

There are countless potential tax strategies, of course, and they don’t all exist in clear categories like “potentially abusive tax shelter” or “legitimate tax-minimization strategy”. But there are a few basic guidelines that advisors can use when determining whether a tax strategy should be left within the purview of a designated tax practitioner:

- Does the strategy involve a Listed Transaction that requires filing disclosures with the IRS?

- Does the strategy involve setting up a separate legal entity (like a business or trust) controlled by the client?

- Does the strategy involve a tax-exempt entity (e.g., a charitable organization) controlled by the client?

- Does the strategy involve a foreign-based entity?

- Does the strategy involve a transaction with an individual who is related to the taxpayer in order to shield income or assets from taxation?

- Does the strategy involve interpretation between the lines of existing tax laws or regulations (as opposed to optimizing taxation within the lines of existing law)?

If the answer to any of these questions is yes, the strategy should likely be left to an attorney, CPA, or EA to recommend (or be recommended in conjunction with one, where the advisor works with, and gets the ‘sign off’ from, the tax professional who will accept responsibility for the Tax Advice recommendation).

How To Recommend Tax Strategies In Conjunction With A Tax Professional

That isn’t to say that FLPs and other complex strategies shouldn’t be recommended at all. Any strategy that is (1) legal and (2) able to help a client better achieve their goals is, in theory, fair game for consideration. The key consideration for financial advisors is whether or not they are the ones making the recommendation, since that recommendation is ultimately what constitutes the ‘Advice’ part of Tax Advice.

If a strategy involves an interpretation of tax rules or a type of transaction or entity designed to avoid taxes as discussed above, then advising on it likely constitutes the type of ‘practice before the IRS’ that only attorneys, CPAs, and EAs are allowed to practice, and the recommendation should not be made by the advisor alone. What constitutes a recommendation? Putting a specific set of action steps together to implement the strategy and proposing that the client go through with them – all of which would pretty clearly be considered tax advice by almost any definition.

How can an advisor go about recommending one of the above strategies? There is a 3-step process that advisors can follow for strategies that clearly require the involvement of a designated tax professional:

- The advisor sketches out a plan for the strategy and analyzes its impact on the client’s long-term financial picture. They may also choose to discuss it with the client as long as it is clear that the advisor is not yet recommending the strategy.

This step can involve the advisor alone since merely considering a strategy is unlikely to cross the line into tax advice, since it doesn’t go so far as to make a concrete plan or suggest a course of action for the client.

- The advisor and the client’s tax professional discuss the details of how the strategy would be implemented in practice.

In this stage, it’s important for the advisor to ensure that the client’s tax professional is aware of any of the client’s broader circumstances that might affect how the strategy is implemented.

- The advisor and tax professional propose the plan of action to the client.

This might be done in a joint meeting with the advisor, tax professional, and client, or it could be in a meeting with just the client and advisor with the recommendation written in a letter from the tax professional. Either way, it should be clear that the recommendation itself – the proposal to implement the strategy, and the steps involved in doing so – is coming from the tax professional, not the advisor alone.

In practice, the idea to use one of these strategies might well come from the financial advisor, who is uniquely positioned to have a holistic view of the client’s financial situation and may be well-versed in a broad range of strategies; the advisor can collect relevant financial information from the client and analyze the strategy’s potential impact. But at some point, a handoff must occur: The client’s tax professional should be the one who lays out the recommended course of action to the client (or at the very least, they should give their written approval of the strategy that the advisor then brings to the client).

Avoiding Compliance And Liability Issues When Giving Tax Advice

As mentioned earlier, there are types of tax advice given by financial advisors that aren’t the sort of tax avoidance schemes that would likely be scrutinized as Tax Advice by the IRS, but are intended to optimize the timing or type of income that is recognized based on clear and established tax rules (e.g., Roth conversions and asset location recommendations). And yet, despite being allowed from a regulatory standpoint, advisors making these recommendations often face resistance from another source: their own compliance departments.

This begs the question: If there are no restrictions from government regulators on giving this type of tax advice (as long as it doesn’t constitute formal Tax Advice), why are compliance departments so adamant that advisors not get involved with taxes?

The answer comes down to the legal and/or financial liability exposure for the advisor if the advice is wrong, and what a firm or advisor could potentially be sued for if the advisor gives an improper recommendation. Even when a recommendation doesn’t involve tax avoidance as described above, an advisor would be liable for the outcome if it turned out that they didn’t understand the rules properly or didn’t implement them correctly, resulting in higher taxes or penalties for the client.

Of course, when a financial advisor gives any type of recommendation – whether it is about a specific investment, an investment strategy, or a tax matter – and the client is not satisfied with the outcome, there is a potential legal liability: The client can sue the advisor (and their firm), or bring the case before arbitration if allowed, for any damages incurred as a result of the advice.

However, when the issue is investment-related, advisory firms are generally well-protected: They are required by the SEC or state regulators to have supervisory policies and procedures in place to ensure that advisors make recommendations in their clients’ best interests and inform clients of the risks involved with investing. If the advisor has those procedures in place and shows that they followed them, they can often avoid being found liable for a client loss (e.g., if the loss is the result of normal market fluctuations and not the advisor’s failure to exercise due diligence or inform the client about the risks of the investment). And even if the judge or arbitrator does find liability, the firm will generally be covered by its Errors & Omissions (E&O) insurance policy.

But when the issue is a tax matter, many firms haven’t developed policies or procedures relating to giving tax advice and ensuring that the firm’s advice is appropriate. This could be because no regulator has required them to do so, or because many firms simply don’t have the in-house expertise in taxes to be able to supervise their advisors effectively. Either way, the lack of such policies and procedures, or the in-house expertise to ensure advisors are trained and their recommendations are accurate, means that an advisory firm is much more vulnerable to liability from an advisor giving a tax-related recommendation than they would an investment recommendation.

Furthermore, some E&O policies explicitly exclude from their coverage any taxes or penalties owed by a client as a result of the advisor’s tax recommendation. So tax advice can create a true liability for an advisory firm – not in the eyes of the IRS, but from the client who may be harmed if the advice is incorrect (i.e., has an error or an omission)… which makes it understandable that many firms would want to avoid tax topics entirely.

This leaves advisors and their compliance departments with a challenging dichotomy between providing the most value to their clients by engaging in tax planning and protecting the client, firm, and advisor from potential issues and liability (e.g., by avoiding tax advice that goes beyond the expertise of the advisor). Not because advisors can’t legally give at least some kinds of tax advice, but simply because their firms (especially in the case of large firms that have to supervise a lot of advisors) may not be willing to accept the legal liability exposure that comes with allowing their advisors to provide it.

How To Offer Tax Planning Without Actually Giving Tax Advice

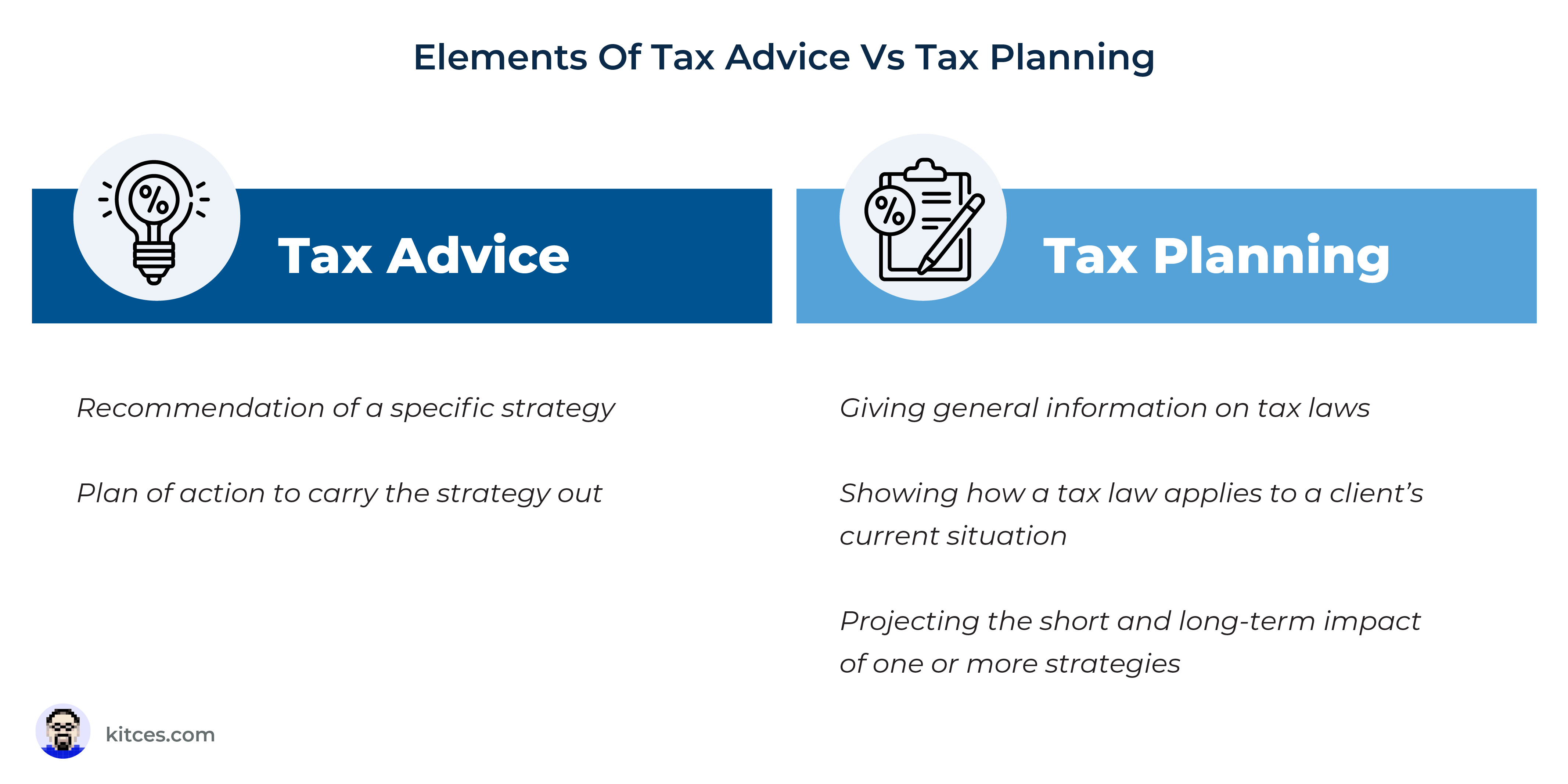

To further understand the nuances of tax advice and how to navigate the challenging area of making tax recommendations, it helps to envision 2 different ways of working with clients on tax-related matters:

- Tax advice (which can be defined as making a recommendation of a plan of action on a tax strategy); and

- Tax planning (which can be defined as the consideration, analysis, and/or projection of tax strategies without taking the step of making a recommendation).

Tax advice can either entail recommendations involving the kinds of tax avoidance strategies commonly scrutinized by the IRS and requiring the involvement of an attorney, CPA, or EA, or other more benign strategies, like following clearly established rules (that aren’t restricted to designated professionals) to optimize the timing and type of income to reduce tax exposure. The key components of both are the recommendation to implement a specific strategy, and the plan of action for doing so.

Tax planning, on the other hand, covers a range of activities that can help demonstrate the potential impact that a tax strategy could have on the client’s financial situation, but that don’t include the recommendation of specific actions that would constitute tax advice.

It can involve applying tax laws and regulations to the client’s circumstances, such as when running a tax projection in financial planning software for the client. It could also include showing the consequences of following a certain strategy. It could even involve comparing the differences between multiple strategies. But it doesn’t go so far as to recommend a specific course of action, which makes tax planning a useful tool for advisors who want to avoid giving tax advice (either because the strategy they are considering would be a tax avoidance strategy requiring a designated tax professional, or because they are prohibited from their compliance department from doing so).

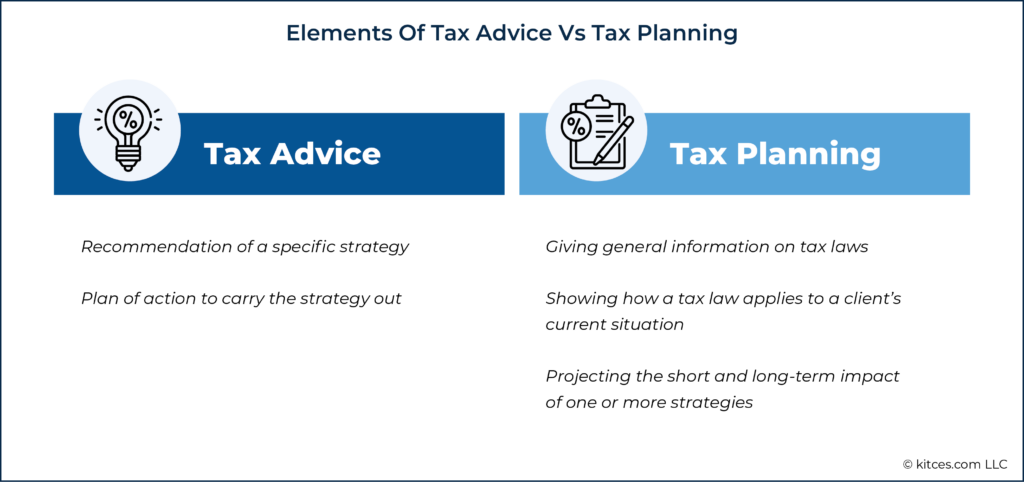

How does tax planning differ from tax advice in practice? It’s helpful to draw from some real-world examples to illustrate what could or could not constitute a recommendation that crosses the line into tax advice.

As shown in the examples above, tax advice tends to be definitive and precise in its statements, focusing on the actions that clients should take to follow a certain strategy. Tax planning, while still being actionable, focuses more on helping the client understand the outcomes of the strategy.

The Spectrum Of Tax Planning From General To Specific

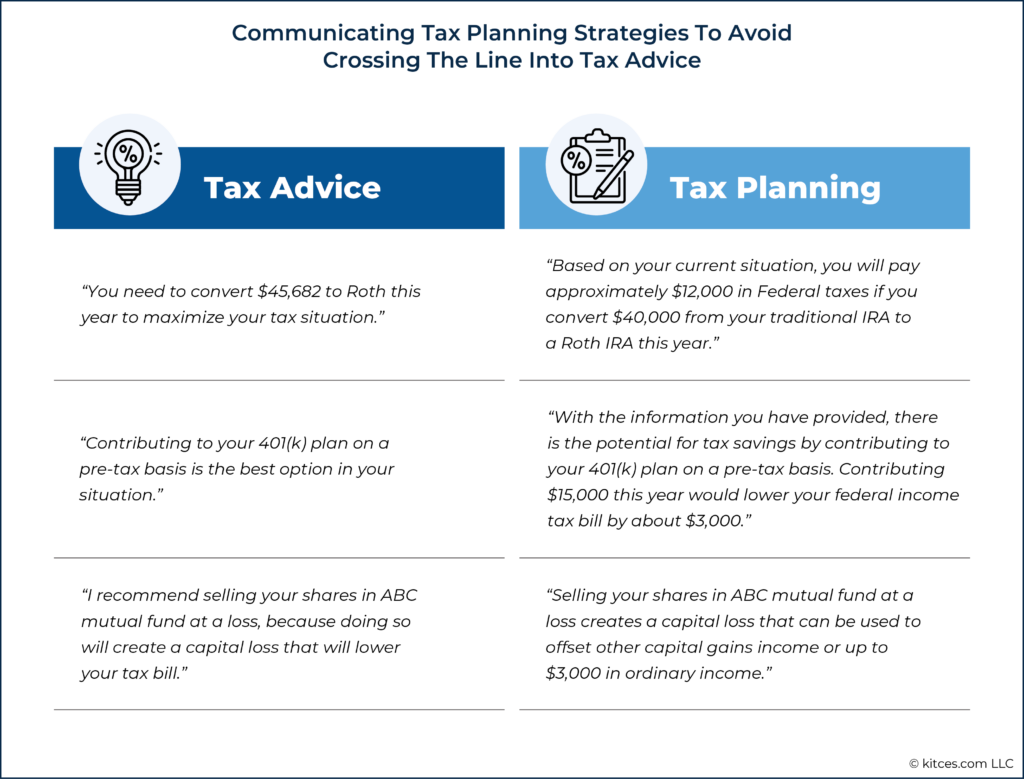

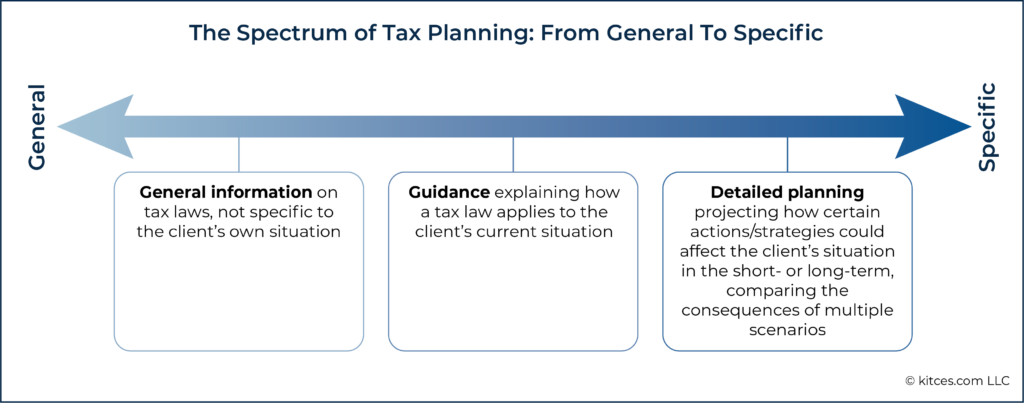

Notably, however, there are still many ways to define how tax advice is given, and even the above examples of tax planning might skew too close to a recommendation for some to be comfortable with. How, then, will advisors know how to proceed?

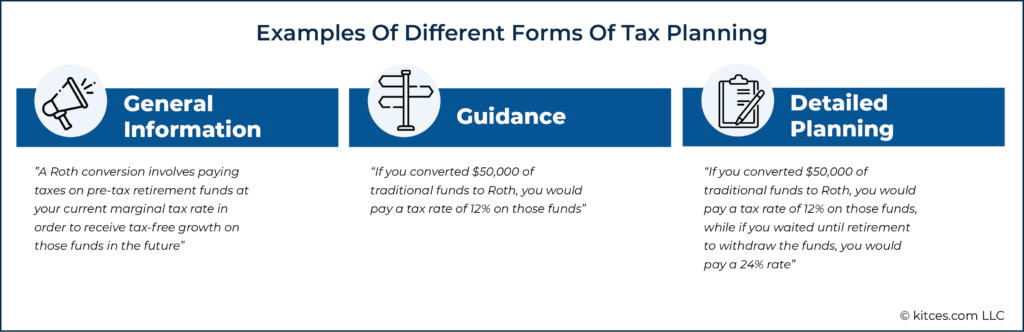

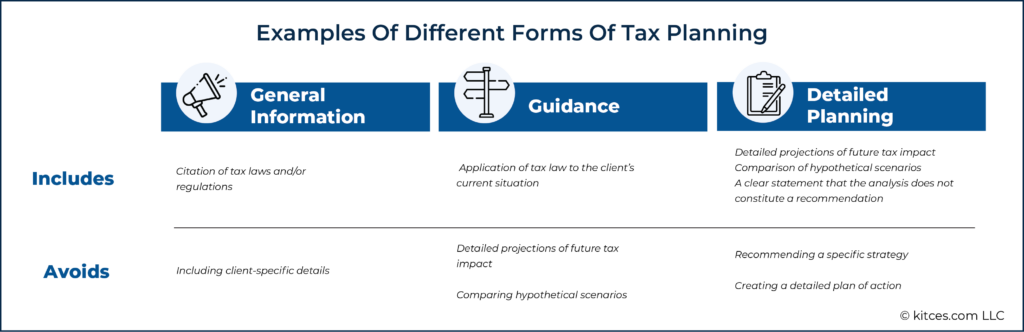

It can be helpful to envision the scope of tax planning as a spectrum. All the way at one end, there is general tax information: Simply stating what the tax rules and regulations say without getting any more specific about what that means for the client. This might be helpful to a limited extent in educating clients on general tax matters, but it doesn’t really contain anything actionable to help the client make a decision.

On the other far end, there are much more specific types of planning, such as running detailed projections of specific strategies based on the client’s own circumstances. This can provide details that can help the client come to a decision on their own; however, if the analysis becomes so detailed that it could possibly be construed as a recommendation, that may make compliance departments nervous about the potential liability of an advisor giving inadvertent tax advice.

In between the two extremes of the spectrum lies what can be called tax guidance – that is, explaining how tax laws apply to a client’s current situation but not providing further detailed analysis that might lead to a decision (and which could therefore be construed as advice).

Again, real-world examples can help illustrate how these forms of tax planning can be applied in practice:

The most conservative compliance departments may only allow very general types of tax planning that involve little more than communicating what is written in tax laws and regulations. Others may be slightly more comfortable with applying the tax code to individual client situations – for instance, as in the examples above that explain the impact of a certain action – but not with putting detailed projections together or comparing hypothetical strategies.

As advisors develop their own tax expertise, however, and make use of increasingly powerful tax planning software that can create detailed projections of tax strategies, they may want to engage with clients in more detailed tax planning conversations. But the more detailed the analysis, the more important it becomes to take care to avoid anything that could be construed as a recommendation.

For example, say that an advisor’s illustration of a strategy to a client includes showing the steps they would take to follow it, then demonstrating how doing so would clearly have a beneficial impact. It’s easy to see how that illustration could be considered to cross the line into tax advice, even if the advisor never formally stated that they recommended it.

Advisor Best Practices To Successfully Implement Tax Planning

There are several best practices that advisors can follow to engage in tax planning without giving tax advice. Where the line is may depend on a number of factors, including the expertise and experience of the individual advisor and their firm’s policies around tax advice, but the following are general principles that will help guide the process:

- Use ranges. Instead of an exact number, provide a range. This makes it clear to the client that they have options, that there isn’t one magic or perfect answer, and that, ultimately, they need to choose a course of action based on your recommendation.

- Clarify the data. Taxes are impacted by a variety of factors. When communicating an analysis or projection of strategies, make it clear what factors have been considered (or not) to evaluate the outcome.

- Set expectations. Make it clear to the client why the strategy is worth considering and what the potential benefit to them will be – but also state plainly when it is necessary for the client to go to their tax professional to recommend a course of action.

- Involve other professionals. If the outcomes of a tax planning strategy aren’t reported to the IRS correctly, it may as well not have happened. Collaborating with a client’s tax preparer is a great way to ensure accuracy and get a second opinion on the recommendations an advisor is making.

An example of a conversation illustrating these practices in action could sound like the following:

Based on your expected salary of $150,000 from your employment and the $100,000 of income from your spouse’s business, we expect you will be in the 24% bracket this year for Federal taxes.

In line with the strategy we have discussed for optimizing your taxes over the lifetime of your wealth, we recommend that you convert between $35,000 and $45,000 from traditional to Roth IRA, which would result in $8,400 to $10,800 in additional Federal taxes this year.

We want to make sure this fits in with your overall tax situation and would highly recommend that you discuss this strategy with your tax preparer to determine the exact amount to convert. We would be happy to coordinate that conversation and share our recommendations with them.

The key point is that the advisor’s idea of what constitutes tax planning versus tax advice is less important than what the client thinks. If the client construes the advisor’s guidance about a certain strategy as a specific recommendation with concrete action steps, then it is as if the advisor has given them tax advice, no matter how carefully the advisor has shaped their language to avoid it.

The more specific and detailed an advisor gets in their communication of the strategy, the more careful they need to be to make it clear to the client that they are not making a formal recommendation, and/or that the client still needs to consult their tax professional to get advice on whether they should go forward with the strategy.

This underscores the importance of being clear about the scope of the advisor’s services throughout the financial planning process. If the advisor gives any of the above recommendations without having ever stated that their services don’t include tax advice, the client might be confused about the vagueness of the recommendations and push for more clarification – which puts the advisor in the awkward position of needing to explain why they can’t provide it.

On the other hand, if the advisor includes statements such as the following in their initial prospect conversations, client agreement, and financial planning materials…

Our financial planning process includes investment recommendations and provides tax guidance, but it is not meant to represent formal tax advice.

…then it is clearer to the client that in order to receive specific tax advice, they will need to hire a specific (and separate) tax professional.

Putting It All Together

With the above framework, it’s possible to create a flowchart or decision tree to help decide when a tax strategy requires the involvement of a designated tax professional – either because the strategy involves a form of tax avoidance that would be considered practicing before the IRS, or because giving tax advice is simply not allowed by the compliance department of the advisor’s firm.

If the advisor can’t give advice on a strategy, they can follow the 3-step Consideration, Consultation, and Recommendation process described above. Otherwise, if they are allowed to give tax advice, they can analyze and recommend the strategy on their own, without the middle step of consulting with a tax professional (though they can certainly choose to do so in order to bolster their recommendation).

If the advisor is not allowed to give tax advice on a certain strategy, the next step is to decide on the extent of the tax planning that they want to engage with the client on (which likely happens during the Consideration step of the process above). Can they create detailed tax projections and compare scenarios? Are they limited to providing guidance on how a tax law applies to the client’s current situation? Or can they only give general information on tax law without including client-specific details?

Compliance departments should be able to give details on the level of specificity advisors can use in their tax planning and what actions they can take to prevent tax planning from being taken for tax advice by clients.

Actions Advisors Can Take Today

The first step is making a commitment to provide value through tax planning. Rather than avoiding tax planning altogether, advisors who are clear-eyed about the fact that most of their advice constitutes tax advice in one way or another can focus on how to make that advice as valuable as possible – and on communicating that value to current and prospective clients.

Second, advisors can work with their compliance departments and supervisors to get clarity about what is and isn’t allowed. For advisors at larger firms, the reality is that there might be little flexibility in firm rules; in those cases, the advisor might be limited to what is stated as firm policy. But in smaller practices, advisors might be able to work with their compliance teams to build a framework that fits both the advisor and the firm.

Third, advisors can build up their own expertise in tax. Doing so not only allows the advisor to use that expertise to provide value for clients, but they can also start to recognize what types of tax practices and strategies are widespread in the industry. This allows advisors to create a process to identify and fill in gray areas of the Internal Revenue Code and to recognize which strategies might yet require a CPA or tax attorney’s sign-off before recommending them to a client.

There is tremendous value provided to clients by advisors incorporating tax planning into their processes. Even CFP Board’s Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct emphasizes taxes as an important consideration for CFP professionals in both understanding the client’s personal and financial circumstances and identifying and selecting goals – though it also emphasizes that advisors should be clear about the scope of their engagements, and only provide where they have sufficient expertise or competency.

For any advisor who holds themselves out as a fiduciary, the question then is not about whether tax planning should be offered, but on how they can incorporate tax planning into their overall processes to give clients the most value!

Our best-selling course, “How To Find Planning Opportunities When Reviewing A Client’s Tax Return,” has now been updated with the most recent numbers and policies. Build the comprehension, application, and client conversation skills to identify and discuss tax strategies with clients!