Executive Summary

For investment advisers looking to attract prospective clients, advertising the performance of their investment strategies would be a logical way to market their services (at least if they had strong historical returns!). But for many years, advisers looking for guidance from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regarding what kind of performance advertising was permissible had to rely on fairly general guidelines and SEC staff statements in the form of “no-action” letters. But now, as part of its recently overhauled Marketing Rule (which also clarifies the rules surrounding investment adviser testimonials and endorsements), the SEC has codified its previous guidance regarding performance advertising into a single, fairly prescriptive rule.

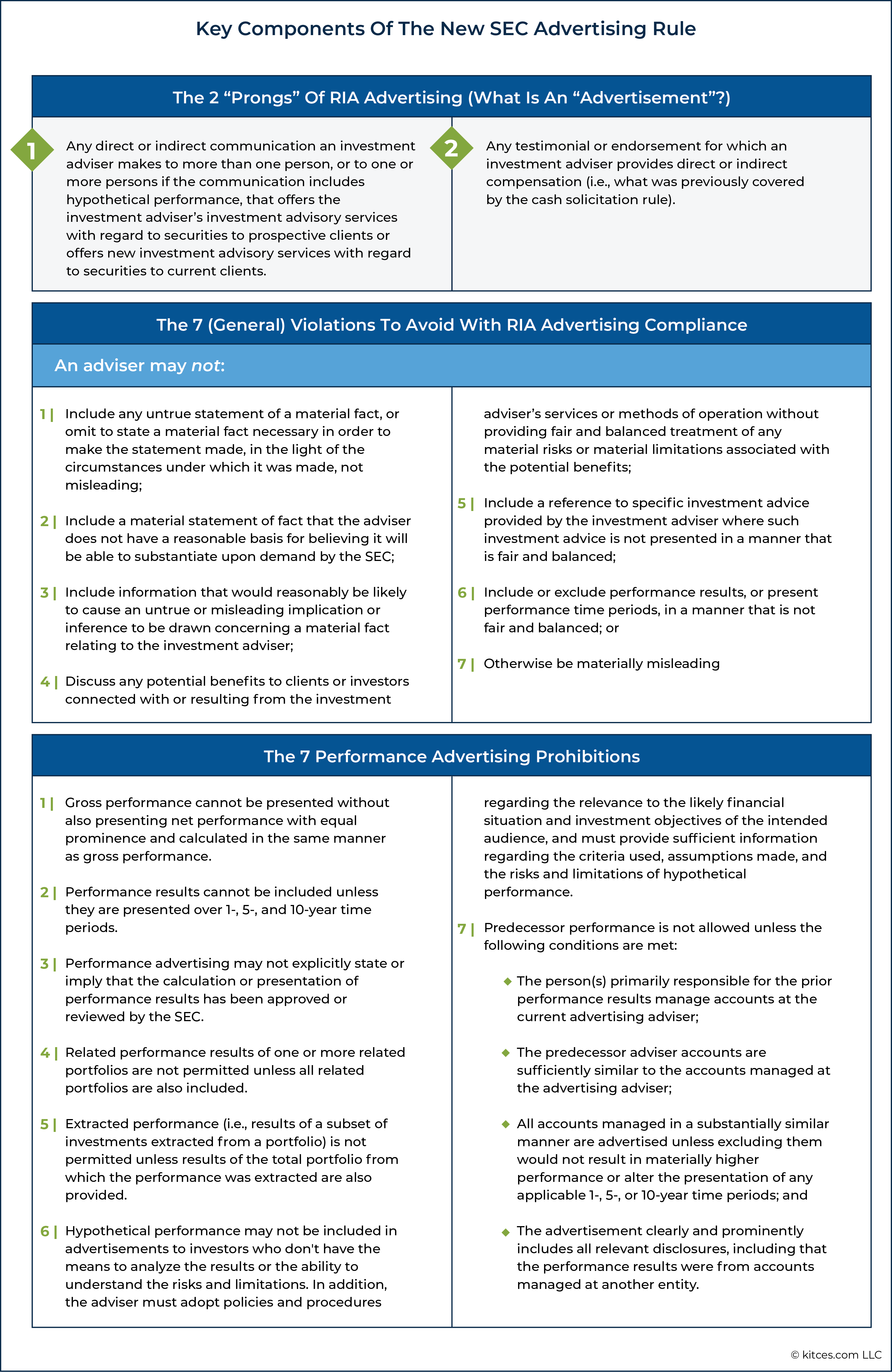

To start, while the Marketing Rule contains seven general prohibitions applicable to all investment adviser advertising activities (including testimonials, endorsements, and third-party ratings, covered in a previous Nerd’s Eye View post), there are seven additional prohibitions applicable specifically to performance advertising. The first rule prohibits advisers from presenting gross performance without also presenting net performance with at least equal prominence, so that investors can assess returns that are actually received, net of fees and expenses paid in connection with the adviser’s services, and helping prospective clients better compare returns across different advisers.

The Marketing Rule also requires performance results to be presented consistently over 1-, 5-, and 10-year time periods (or the time period the portfolio has existed, if shorter than a particular prescribed period) preventing advisers from cherry-picking time periods that would make their returns appear more favorable. Furthermore, investment advisers may generally reference the performance results of related portfolios only if all related portfolios are included in the advertisement. Further, an investment adviser is prohibited from advertising performance results of a subset of investments extracted from a portfolio unless the advertisement provides, or offers to provide promptly, the performance results of the total portfolio from which the performance was extracted.

The SEC has heavily scrutinized the use of hypothetical performance in advertising for many years, and its restrictive stance is codified in the updated Marketing Rule. What actually constitutes hypothetical performance is quite broad and essentially includes any performance result that was not actually achieved by a portfolio of the investment adviser, and its distribution is limited to investors who are considered capable of independently analyzing the information and understanding the associated risks and limitations. Two final prohibitions under the Marketing Rule include restrictions on the use of predecessor performance (e.g., performance by an investment adviser before it was spun out from another adviser or by its personnel while they were employed elsewhere), as well as advertising that explicitly states or implies that that the calculation or presentation of performance results has been approved or reviewed by the SEC.

Ultimately, the key point is that the SEC’s recently overhauled Marketing Rule provides a consolidated set of guidelines for advisers to understand how RIAs are permitted to use advertising. Though, given the potential for future SEC guidance clarifying the new rule, or even possible Risk Alerts summarizing common deficiencies and best practices it observes during the course of its upcoming examinations, advisers looking to use performance advertising will want to pay close attention to how it is enforced in practice!

While the SEC’s recently overhauled Marketing Rule has received significant attention primarily for its newfound permissibility with respect to investment adviser testimonials and endorsements, there’s another equally significant component of the Marketing Rule worth discussing: performance advertising. This component of the Marketing Rule synthesizes myriad SEC no-action letters and guidance over the past several decades and codifies them into a single, fairly prescriptive rule.

SEC-registered investment advisers (and those state-registered investment advisers that are registered in states that defer to the SEC’s Marketing Rule) would do well to familiarize themselves with the Marketing Rule, as the SEC has signaled in a recent Risk Alert that it intends to examine investment advisers to confirm their compliance with the new Marketing Rule:

The staff will conduct a number of specific national initiatives, as well as a broad review through the examination process, for compliance with the Marketing Rule.

Though the Marketing Rule was first adopted on December 22, 2020, and became effective on May 4, 2021, an 18-month transition period between the effective date and the compliance date was provided, which means that the final compliance deadline was November 4, 2022. In other words, full compliance with the Marketing Rule – including the performance advertising provisions discussed in this article – is required as of November 4, 2022.

For an overview of the Marketing Rule overall, as well as a deep-dive into the provisions related to testimonials, endorsements, and third-party ratings, readers are encouraged to refer to this prior article first. In it, you will find a discussion of important threshold subjects, such as what actually constitutes an “advertisement” that is subject to the Marketing Rule and the seven general prohibitions applicable to investment adviser advertising. These threshold subjects apply equally to testimonials, endorsements, and third-party ratings, as discussed in the above-referenced prior article, as well as to performance advertising, as discussed in this article.

The following summarizes the salient points from the prior article around the definition of “advertisement”:

- The first prong of the two-pronged definition of advertisement includes “Any direct or indirect communication an investment adviser makes to more than one person, or to one or more persons if the communication includes hypothetical performance, that offers the investment adviser’s investment advisory services with regard to securities to prospective clients or investors in a private fund advised by the investment adviser or offers new investment advisory services with regard to securities to current clients or investors in a private fund advised by the investment adviser.” (The second prong relates to endorsements and testimonials that an investment adviser provides direct or indirect compensation for, as discussed previously.)

- Excluded from this first prong of “advertisements” are:

- Extemporaneous, live, oral communications;

- Information contained in a statutory or regulatory notice, filing, or other required communication; and

- Unsolicited information regarding hypothetical performance or one-on-one communications with private fund investors that includes hypothetical performance.

- One-on-one communications with a single person (or household) are not an advertisement for purposes of the first prong unless such communication includes hypothetical performance (though such communications are generally still subject to the standard Books and Records requirement to retain such communications). One-on-one communications that do include hypothetical performance will be deemed advertising unless such communication was in response to an unsolicited prospective or current client (or an investor in a private fund advised by the adviser) who requested such information. Bulk emails, templates, and other communications that appear to be personalized (e.g., by changing the addressee’s name) are considered advertisements.

- To be considered an advertisement under the first prong, the communication must offer the adviser’s services with regard to securities. Communications that include generic brand content, purely educational material, market commentary, and event sponsorship, by themselves, are not deemed to be advertisements. In other words, it’s not an advertisement to “raise the profile of the adviser generally” or to communicate “general information about investing, such as information about types of investment vehicles, asset classes, strategies, certain geographic regions, or commercial sectors.” However, such non-advertisements would at least partially become advertisements if the communication includes a description of how the adviser’s securities-related services can help the recipient of the communication.

- An advertisement may be made either directly by the adviser or indirectly by a third party. Whether a third-party communication will be deemed an advertisement of the adviser depends on the extent to which the adviser has adopted or entangled itself in the third-party communication. The degree of “adoption and entanglement” is a facts and circumstances analysis of “(i) whether the adviser has explicitly or implicitly endorsed or approved the information after its publication (adoption) or (ii) the extent to which the adviser has involved itself in the preparation of the information (entanglement).”

- Communications designed to retain existing clients are not advertisements, even if sent to more than one existing client. However, communications designed to offer new advisory services to existing clients, if sent to more than one existing client, are advertisements.

- Extemporaneous, live, and oral communications are excluded from the definition of advertisement under the first prong. Such communications would not be captured by the first prong “regardless of whether they are broadcast/webcast and regardless of whether they take place in a one-on-one context and involve discussion of hypothetical performance.” However, communications prepared in advance (such as prepared remarks, speeches, scripts, slides, etc.) are not excluded under this particular carve-out. Similarly, the dissemination of a recorded communication (like a recorded webinar, speech, etc.) will be an advertisement if it otherwise meets the definition of advertisement by relating to advisory services with regard to securities.

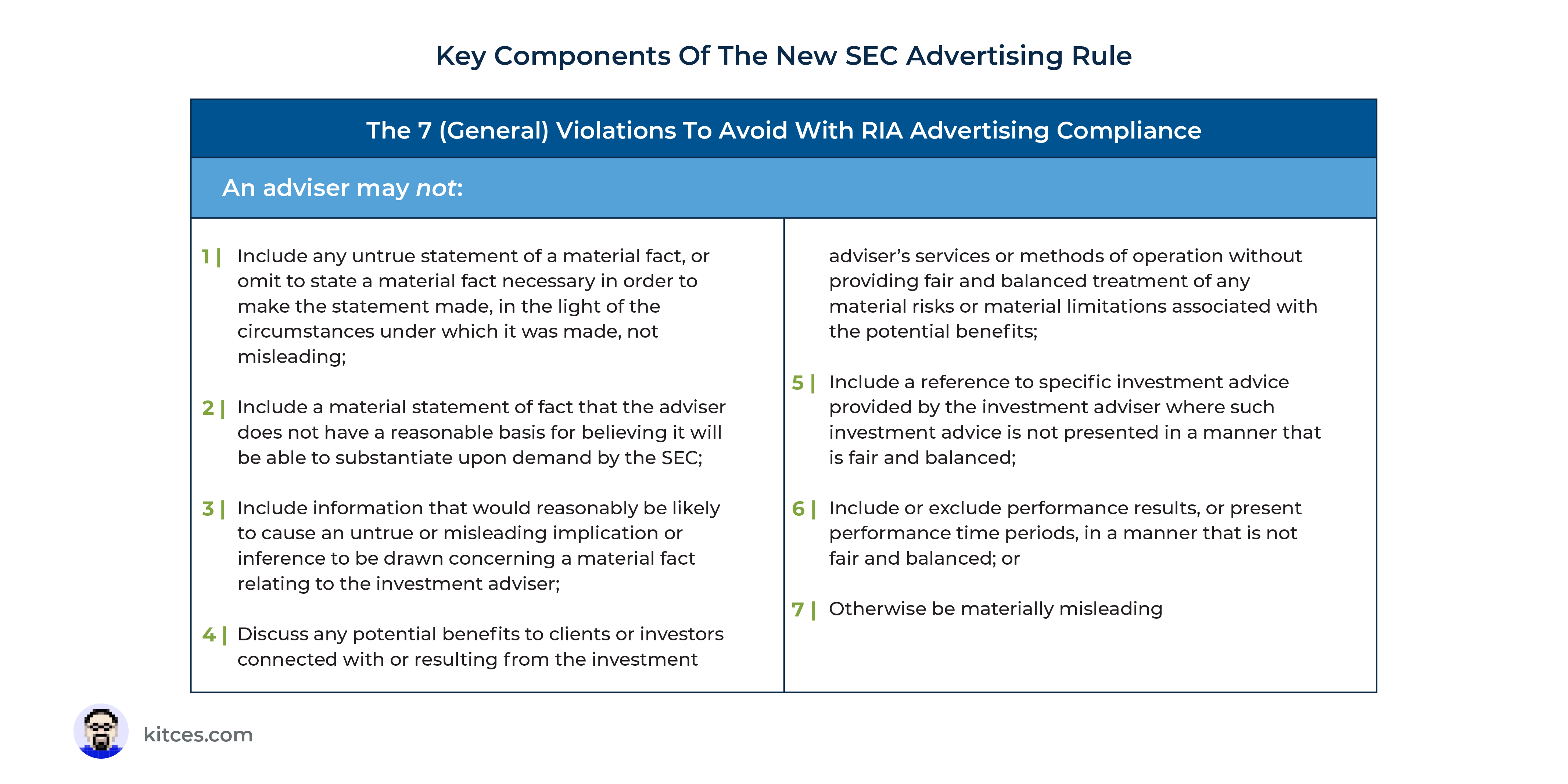

Additionally, as a means of preventing “fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative acts” by advisers, the Marketing Rule contains seven general prohibitions such that an adviser may not:

- Include any untrue statement of a material fact, or omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statement made, in the light of the circumstances under which it was made, not misleading;

- Include a material statement of fact that the adviser does not have a reasonable basis for believing it will be able to substantiate upon demand by the Commission;

- Include information that would reasonably be likely to cause an untrue or misleading implication or inference to be drawn concerning a material fact relating to the investment adviser;

- Discuss any potential benefits to clients or investors connected with or resulting from the investment adviser’s services or methods of operation without providing fair and balanced treatment of any material risks or material limitations associated with the potential benefits;

- Include a reference to specific investment advice provided by the investment adviser where such investment advice is not presented in a manner that is fair and balanced;

- Include or exclude performance results or present performance time periods in a manner that is not fair and balanced; or

- Otherwise be materially misleading.

With the definition of advertisement and the seven general prohibitions now laid forth, let’s next transition to a brief history of how the SEC regulated performance advertising, and how that history informed the performance advertising components of the Marketing Rule.

A Brief History Of SEC Performance Advertising Regulation

Before the ‘new’ Marketing Rule’s adoption in 2020, the current “Investment Adviser Marketing” rule (Rule 206(4)-1) was previously entitled “Advertisements by investment advisers”, and it did not directly address performance advertising at all… at least not nearly to the level of detail that the new Marketing Rule does. The prior rule imposed restrictions with respect to the advertising of an investment adviser’s past specific investment recommendations, but performance advertising was otherwise swept into the general catch-all prohibition against any advertisement that contained an “untrue statement of a material fact, or which is otherwise false or misleading.”

Notwithstanding that the prior rule did not directly circumscribe performance advertising, this shouldn’t be taken to mean that performance advertising was wholly unregulated. To the contrary, it was, in fact, highly regulated – only indirectly through the publication of SEC staff statements (also known as “no-action letters”) and guidance updates published over the decades leading up to the 2020 overhaul.

Nerd Note:

If you’re ever bored to such an extreme that you wish to peruse the entirety of SEC no-action letters that have been made publicly available through the SEC’s website, direct your browser to this website to embark on your journey to the unparalleled depths of tedium.

A no-action letter is initiated by a written request made by a member of the public to the staff of the SEC (notably, not to the actual Commission or Commissioners, but instead to the staff of one of the divisions within the SEC). If the SEC staff deems the inquiry worthy, it responds in the form of a publicly available letter that is intended to provide at least some comfort to the inquirer that its facts and representations would not result in an SEC enforcement action; in other words, that the SEC staff would not take adverse action (thus, the ‘no-action’ moniker) against the inquirer.

As one can imagine, each no-action letter is laden with disclosures to the effect that it is solely based on the facts and representations made by the inquirer; it does not present any legal or interpretive position on the issues presented; different facts or representations may require a different conclusion; it only represents the views of the particular SEC division to whom the inquiry was originally addressed; it is not a rule, regulation, or statement of the SEC itself; and the SEC has neither approved nor disapproved its content.

Even with the litany of disclosures and disclaimers that seem to undermine the usefulness and reliability of no-action letters, these letters became an integral part of the regulatory zeitgeist, effectively dictating how investment advisers were to advertise their performance for the period of time leading up to the Marketing Rule’s overhaul in 2020.

The seminal no-action letter that arguably had the most significant, direct impact on investment adviser performance advertising was Clover Capital Management, Inc., October 28, 1986. In brief, this no-action letter was a response to an inquiry around the firm’s use of “investment results derived from a ‘model’ portfolio in advertisements” and, in justifying its ‘no-action’ conclusion, clarified the SEC staff’s view that the (former) rule would prohibit an advertisement that:

- Failed to disclose the effect of material market or economic conditions on the results portrayed;

- Included model or actual results that did not reflect the deduction of advisory fees, brokerage or other commissions, and any other expenses that a client would have paid or actually paid;

- Failed to disclose whether and to what extent the portrayed results reflect the reinvestment of dividends and other earnings;

- Suggested or made claims about the potential for profit without also disclosing the possibility of loss;

- Compared model or actual results to an index without disclosing all material facts relevant to the comparison;

- Failed to disclose any material conditions, objectives, or investment strategies used to obtain the results portrayed;

- Failed to disclose the limitations inherent in model results prominently;

- Failed to disclose, if applicable, that the conditions, objectives, or investment strategies of the model portfolio changed materially during the time period portrayed in the advertisement;

- Failed to disclose, if applicable, that any of the securities contained in, or the investment strategies followed with respect to, the model portfolio do not relate, or only partially relate, to the type of advisory services currently offered by the adviser;

- Failed to disclose, if applicable, that the adviser’s clients had investment results materially different from the results portrayed in the model; and

- Failed to disclose prominently, if applicable, that the results portrayed relate only to a select group of the adviser’s clients, the basis on which the selection was made, and the effect of this practice on the results portrayed, if material.

Suffice it to say, there was a lot of meat on the bone of the Clover no-action letter, and it remained on the short list of any investment adviser compliance professional’s reference list (including my own) when reviewing an investment adviser’s performance advertising. Several other important no-action letters related to performance advertising followed, but Clover was the OG.

In a somewhat bittersweet turning of the page, the SEC released a laundry list of no-action letters and guidance updates that would be withdrawn in connection with the November 4, 2022, compliance date of the Marketing Rule. The Clover no-action letter is one such no-action included in the list. It was a good run.

For a complete list of the prior SEC staff statements and guidance updates that have been withdrawn, refer to the Division of Investment Management Staff Statement Regarding Withdrawal and Modification of Staff Letters Related to Rulemaking on Investment Adviser Marketing. The primary takeaway is that the SEC no-action letters and guidance updates that were once the foundation of an investment adviser’s performance advertising are no more and are effectively superseded by the Marketing Rule.

The Seven Performance Advertising Prohibitions

With the foundational definition of advertisement and the seven general prohibitions that apply to all investment adviser advertising now laid, and a brief history of investment adviser performance advertising now covered, we can turn to the seven specific prohibitions applicable to performance advertising as discussed below.

Gross & Net Performance

An advertisement may not include a presentation of gross performance without also presenting net performance “(i) With at least equal prominence to, and in a format designed to facilitate comparison with, the gross performance, and (ii) calculated over the same time period, and using the same type of return and methodology, as the gross performance.”

A presentation of gross performance must thus be accompanied by an equal presentation of net performance, but a presentation of net performance alone need not be accompanied by a presentation of gross performance.

The terms “gross performance” and “net performance” are both defined in the Marketing Rule with reference to another defined term – “portfolio” – which refers to a group of investments managed by the investment adviser (e.g., an account or a private fund of the investment adviser or its affiliates). Both gross and net definitions are fairly intuitive.

Gross performance refers to performance before the deduction of all fees and expenses that a client or investor has paid or would have paid in connection with the investment adviser’s services to the portfolio.

Net performance refers to performance after the deduction of all fees and expenses that a client or investor has paid or would have paid in connection with the investment adviser’s services to the relevant portfolio.

Such fees and expenses include, for example, advisory fees, advisory fees paid to underlying investment vehicles, and payments by the investment adviser for which the client or investor reimburses the investment adviser. On the other hand, net performance may exclude third-party custodian fees (even if the adviser knows the amount of such custodian fees and/or recommends the custodian).

If a model fee is utilized in the advertisement, such model fee must reflect either (i) the deduction of a model fee when doing so would result in performance figures that are no higher than if the actual fee had been deducted; or (ii) the deduction of a model fee that is equal to the highest fee charged to the intended audience to whom the advertisement is disseminated.

The SEC’s goal here was to ensure that the presented performance is no higher than if the investment adviser were to deduct actual fees instead of model fees.

No prescriptive gross/net calculation methodology is required so long as the methodology is appropriate for the particular investment strategy and it does not otherwise violate the seven general prohibitions.

The SEC has clearly signaled that it wants the reductive effects of fees and expenses to be presented such that investors are not under the illusion that they actually received the full amount of the presented gross returns. Fees and costs matter, and – like investment returns – compound over time.

The SEC did not prescribe the exact disclosure requirements that must accompany the presentation of gross and net returns. Investment advisers are instead instructed to refer back to the seven general prohibitions applicable to all advertisements, as discussed earlier in this article.

However, the Marketing Rule’s Adopting Release indirectly suggests that gross/net performance disclosures “may” include the following, as appropriate:

- The material conditions, objectives, and investment strategies used to obtain the results portrayed;

- Whether and to what extent the results portrayed reflect the reinvestment of dividends and other earnings;

- The effect of material market or economic conditions on the results portrayed;

- The possibility of loss;

- The material facts relevant to any comparison made to the results of an index or other benchmark;

- Whether or not cash flows in and out of the portfolio have been included; and

- If a presentation of gross performance does not reflect the deduction of transaction fees and expenses.

Despite the Adopting Release’s coy hedging language, investment advisers are encouraged to incorporate disclosure that addresses each of the above-bulleted considerations to the extent applicable. Disclosing whether or not the reinvestment of dividends or other earnings is reflected, along with the possibility of loss, should be included in nearly all advertisements, including gross/net performance. All index comparisons should also include some description of the index so as to inform the investor’s evaluation of the comparison’s validity. Disclosure regarding material or economic conditions could be appropriate, for example, during such times as the Great Recession or 2022’s inflationary environment.

1-, 5-, And 10-Year Period Reporting

Performance results (other than private fund performance) cannot be included in an advertisement unless they are presented over 1-, 5-, and 10-year time periods with equal prominence and with an ending date no less recent than the most recent calendar year-end. If the relevant portfolio did not exist for a particular prescribed period (e.g., 7 years), then an investment adviser must present performance information for the life of the portfolio (e.g., 1-, 5, and 7 years). Additional time periods may be presented as long as the prescribed time periods are included.

The SEC’s primary goal with these prescriptive time periods is to facilitate comparison among multiple advertisements and to avoid cherry-picking or highlighting only the best-returning time periods. It is for this reason that the Adopting Release additionally suggests that an investment adviser may need to present performance as of a more recent date than the most recent calendar year-end in order to comply with the seven general prohibitions:

It could be misleading for an adviser to present performance returns as of the most recent calendar year-end if more timely quarter-end performance is available and events have occurred since that time that would have a significant negative effect on the adviser’s performance.

Approval By The SEC

This specific prohibition should be obvious, but no performance advertising should explicitly state or imply that the calculation or presentation of performance results has been approved or reviewed by the SEC.

To quote Forrest Gump, “and that’s all I have to say about that.”

Related Performance

Continuing the theme of eliminating the opportunity for investment advisers to cherry-pick performance results, the Marketing Rule imposes specific prohibitions on the use of related performance (i.e., the performance results of one or more “related portfolios,” either on a portfolio-by-portfolio basis or as a composite aggregation of all portfolios falling within stated criteria).

A “related portfolio” is a portfolio with substantially similar investment policies, objectives, and strategies as those of the services being offered in the advertisement. What constitutes “substantially similar” is determined by a facts-and-circumstances analysis (though different fees and expenses alone would not allow an investment adviser to exclude a portfolio that has a substantially similar investment policy, objective, and strategy as those of the services offered).

In other words, an investment adviser’s advertisement may generally only reference the related performance of a related portfolio if all related portfolios are included in the advertisement as well. A related portfolio may only be excluded if the advertised performance results are not “materially higher” than if all related portfolios had been included (and the exclusion does not alter any of the prescribed one-, five-, and 10-year time period reporting requirements). What constitutes “material” in this context is also determined by a facts-and-circumstances analysis.

The inclusion of only related portfolios that have favorable performance results is therefore generally prohibited, subject to the narrow carve-outs described above. The Adopting Release acknowledges that “an adviser will likely be required to calculate the performance of all related portfolios to ensure that the exclusion of certain portfolios from the advertisement meets the rule’s conditions,” but too bad; such is the price of admission to utilizing related performance in advertisements.

The Adopting Release provides a small handful of related performance examples that would likely fail one of the seven general prohibitions: “An advertisement presenting related performance on a portfolio-by-portfolio basis could be potentially misleading if it does not disclose the size of the portfolios and the basis on which the adviser selected the portfolios.” In addition, “omitting the criteria the adviser used in defining the related portfolios and crafting the composite could result in an advertisement presenting related performance that is misleading.”

Extracted Performance

Similar to the framework to be applied to related performance, an investment adviser’s presentation of extracted performance (i.e., the performance results of a subset of investments extracted from a portfolio) is prohibited unless the advertisement provides, or offers to provide promptly, the performance results of the total portfolio from which the performance was extracted.

Squashing out cherry-picking opportunities and facilitating investor comparison opportunities across multiple investment advisers is again the motivating rationale. In addition, the Adopting Release does acknowledge the value of presenting extracted performance, such that it can inform investors with information about performance attribution within a portfolio.

Importantly, performance that is extracted from a composite of multiple portfolios does not fit within the definition of extracted performance due to the increased risk of investment adviser cherry-picking and therefore being misleading to investors. An investment adviser wishing to incorporate a composite of extracts in an advertisement should therefore not look to the extracted performance conditions of the Marketing Rule but should instead look to the Marketing Rule’s prohibitions applicable to hypothetical performance as discussed below.

The final rule does not require an adviser to provide detailed information regarding the selection criteria and assumptions underlying extracted performance unless the absence of such disclosures, based on the facts and circumstances, would result in performance information that is misleading or otherwise violates one of the general prohibitions applicable to all investment adviser advertisements. As with any advertisement, an adviser should take into account the audience for the extracted performance in crafting disclosures.

With respect to cash holdings, the SEC believes it would be misleading under the Marketing Rule to present extracted performance in an advertisement without disclosing whether it reflects an allocation of the cash held by the entire portfolio and the effect of such cash allocation, or of the absence of such an allocation, on the results portrayed.

Hypothetical Performance

Hypothetical performance has always been, and continues to be, the most heavily scrutinized performance advertising. The SEC is demonstrably skeptical of hypothetical performance in general, and its skepticism sets the tone for the overall treatment of hypothetical performance in the Adopting Release: “We believe that such presentations in advertisements pose a high risk of misleading investors since, in many cases, they may be readily optimized through hindsight.”

Before delving into the definition of hypothetical performance and the conditions under which it may be used in investment adviser marketing, it is worth underscoring just how restrictive the SEC intends hypothetical performance to be:

We intend for advertisements including hypothetical performance information to only be distributed to investors who have access to the resources to independently analyze this information and who have the financial expertise to understand the risks and limitations of these types of presentations. […] We believe that advisers generally would not be able to include hypothetical performance in advertisements directed to a mass audience or intended for general circulation.

Said another way, hypothetical performance advertisements may not be distributed to investors (or even to a single investor in a one-on-one setting) that:

- Do not have access to the resources to independently analyze such hypothetical performance; or

- Do not have sufficient financial experience to understand the risks and limitations of hypothetical performance.

If an investment adviser’s prospective clients lack such resources or financial experience, they may not be presented with an advertisement that contains hypothetical performance. In this sense, the SEC is significantly narrowing the universe of investors to whom hypothetical performance can be presented.

Even if the investors to be presented with an advertisement that contains hypothetical performance do have such resources and financial experience, there are still a host of hoops that an investment adviser must jump through. Such an investment adviser must:

- Adopt and implement policies and procedures to ensure that the hypothetical performance is relevant to the likely financial situation and investment objectives of the intended audience;

- Provide sufficient information to enable the intended audience to understand the criteria used and assumptions made in calculating the hypothetical performance (what constitutes “sufficient information” is intentionally not defined; the Marketing Rule does not prescribe any particular hypothetical performance calculation methodology); and

- Provides (or, if the intended audience is an investor in a private fund, provides or offers to provide promptly) sufficient information to enable the intended audience to understand the risks and limitations of using such hypothetical performance in making investment decisions.

What actually constitutes hypothetical performance is quite broad and is essentially any performance result that was not actually achieved by a portfolio of the investment adviser. It includes, but is not limited to:

- Model portfolio performance;

- Backtested performance (i.e., applying a strategy to data from prior time periods when such strategy was not in existence); and

- Targeted or projected performance returns.

Importantly, however, the following are explicitly excluded from the definition of hypothetical performance:

- Interactive analysis tools used by a client or prospective client to produce simulations and statistical analyses of the likelihood of future outcomes so long as the adviser does the following:

- Describes the criteria and methodology used, including its limitations and key assumptions;

- Explains that results may vary with each use and over time and are hypothetical in nature and, if applicable, describes the universe of investments considered in the analysis;

- Explains how the tool determines which investments to select;

- Discloses if the tool favors certain investments and, if so, explains the reason for the selectivity; and

- States that other investments not considered may have characteristics similar or superior to those being analyzed).

- Compliant predecessor performance (discussed below).

The window of opportunity to utilize hypothetical performance is narrow. Even if an investment adviser is able to squeeze through such a window, it should expect scrutiny during the course of an SEC exam.

Predecessor Performance

If an advertisement is to contain performance information obtained by the investment adviser, its personnel, or its predecessor advisory firm in the past as or at a different entity, it must generally navigate the Marketing Rule’s prohibitions with respect to predecessor performance.

Predecessor performance can include performance obtained by an investment adviser before it was spun out from another investment adviser or by its personnel while they were employed by another investment adviser (e.g., while at a former employer). The current investment adviser is thus the “advertising adviser,” even though the performance to be advertised was not directly obtained by the advertising adviser itself and was instead obtained by a “predecessor adviser”.

The use of predecessor performance is contingent on the following:

- The person or persons who were primarily responsible for achieving the prior performance results manage accounts at the advertising adviser;

- The accounts managed at the predecessor adviser are sufficiently similar to the accounts managed at the advertising adviser;

- All accounts that were managed in a substantially similar manner are advertised unless the exclusion of any such account would not result in materially higher performance and the exclusion of any account does not alter the presentation of any applicable 1-, 5-, or 10-year time periods; and

- The advertisement clearly and prominently includes all relevant disclosures, including that the performance results were from accounts managed at another entity.

A mere change of an investment adviser’s brand name, the form of legal organization (e.g., from a corporation to an LLC), or its ownership would not render past performance as predecessor performance needing to satisfy all of the conditions immediately above.

Form ADV Part 1 Disclosure

If an investment adviser has not recently filed an amendment to its Form ADV through the Investment Adviser Registration Depository (IARD), it may not have noticed that Item 5 of Form ADV Part 1 now includes a few additional questions to answer regarding the investment adviser’s advertisements.

Specifically, new Item 5.L (Marketing Activities) calls for “yes” or “no” responses to the following:

- Do any of your advertisements include:

-

- Performance results?

- A reference to specific investment advice provided by you (as that phrase is used in rule 206(4)-1(a)(5))?

- Testimonials (other than those that satisfy rule 206(4)-1(b)(4)(ii))?

- Endorsements (other than those that satisfy rule 206(4)-1(b)(4)(ii))?

- Third-party ratings?

- If you answer “yes” to L(1)(c), (d), or (e) above, do you pay or otherwise provide cash or non-cash compensation, directly or indirectly, in connection with the use of testimonials, endorsements, or third-party ratings?

- Do any of your advertisements include hypothetical performance?

- Do any of your advertisements include predecessor performance?

Not much to discuss with respect to this Form ADV data gathering by the SEC, other than that investment advisers should be prepared to respond to these questions the next time they file an ADV amendment.

Recordkeeping

To reflect the new performance advertising definitions and conditions, the SEC’s Recordkeeping Rule has been revised in lockstep.

In short, investment advisers must make and keep records of all advertisements they disseminate (not just those disseminated to ten or more persons, as under the prior rule), and additional recordkeeping obligations have been imposed specifically with respect to predecessor performance, hypothetical performance, and the retention of “all accounts, books, internal working papers, and other documents necessary to form the basis for or demonstrate the calculation of the performance or rate of return of any or all managed accounts, portfolios, or securities recommendations…”.

In other words, be prepared to show your work.

Though the SEC attempted to consolidate decades of no-action letters into a single, comprehensive rule, time will tell whether further no-action letters, guidance updates, or even FAQs will be necessary to flesh out the inevitable question marks that investment advisers will uncover when attempting to comply with the Marketing Rule and its performance advertising requirements in practice.

In addition, don’t be surprised if, after the SEC gathers sufficient information during the course of its examinations focused on investment advisers’ compliance with the Marketing Rule and its performance advertising requirements, it publishes a Risk Alert summarizing the common deficiencies and best practices it observed.

There is likely much below the surface of the Marketing Rule iceberg yet to rise to the surface.