New episode of Bad Takes is up, about Thomas Frank’s claim that “virtually all the country’s political dynamism has been located on the right.”

During last year’s December news doldrums, I wrote about the under-appreciated long-term improvement in the quality of America’s water — more of our lakes and rivers are swimmable, they are no longer covered with oil slicks that catch on fire, and generally speaking, the revolution unleashed by the Clean Water Act and ongoing technical improvements is working.

Clean Water fans got more good news this December as the Water Resources Development Act of 2022 was incorporated into the National Defense Authorization Act and passed on December 15. It’s a bit of a legislative Christmas tree, as you’d expect from something that ends up with 88 votes in the Senate, but all the major environmental groups are endorsing it with Environmental Defense Fund’s Natalie Snider especially calling out investments to promote climate resilience. But the National Audubon Society says it will also “drive ecosystem restoration,” while the National Estuarine Research Reserve Association says it will “address harmful algal blooms,” and the National Parks Conservation Association is looking forward to “improved water quality for drinking and outdoor recreation.”

The things Congress authorizes in these big bills tend not to end up fully funded when the annual appropriations cycle comes around. So excitement around a big comprehensive bill inevitably has an element of overstatement to it — different groups want to talk up their favorite provisions in hopes of maximizing congressional interest in delivering the funds, but not everything can get maxed out, and someone will be disappointed.

The point, though, is that the Water Resources Development Act does a bunch of useful things.

It also reflects, I think, most people’s broad sense of how politics “ought to” work — it addresses a bunch of topics that earnest progressive activists have put on the radar, but in a non-radical, business-friendly way it emphasizes bipartisanship and problem-solving rather than revolution. Some horses were traded, some deals were struck, the ball is moved forward in a bunch of ways, and it’s a feel-good story about American politics. Except nobody feels good about it because the week this legislation came together, it wasn’t the major story in American politics. Nor was the larger bipartisan NDAA the major story in American politics. The major story is always some form of ugly fighting, and because Congress wasn’t doing much ugly fighting, the main story instead became Elon Musk fighting with various journalists. One of my theses (developed with Simon Bazelon) has been that this is not a coincidence — it’s easier for Congress to get things done when it’s quiet, but having most of the good parts of politics languish in obscurity feeds cynicism, just as few people know the underlying story of improving water.

One of the bill’s provisions that’s probably not so consequential for most people but is interesting to me personally is that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is directed to identify some good locations for swimming beaches in the District of Columbia.

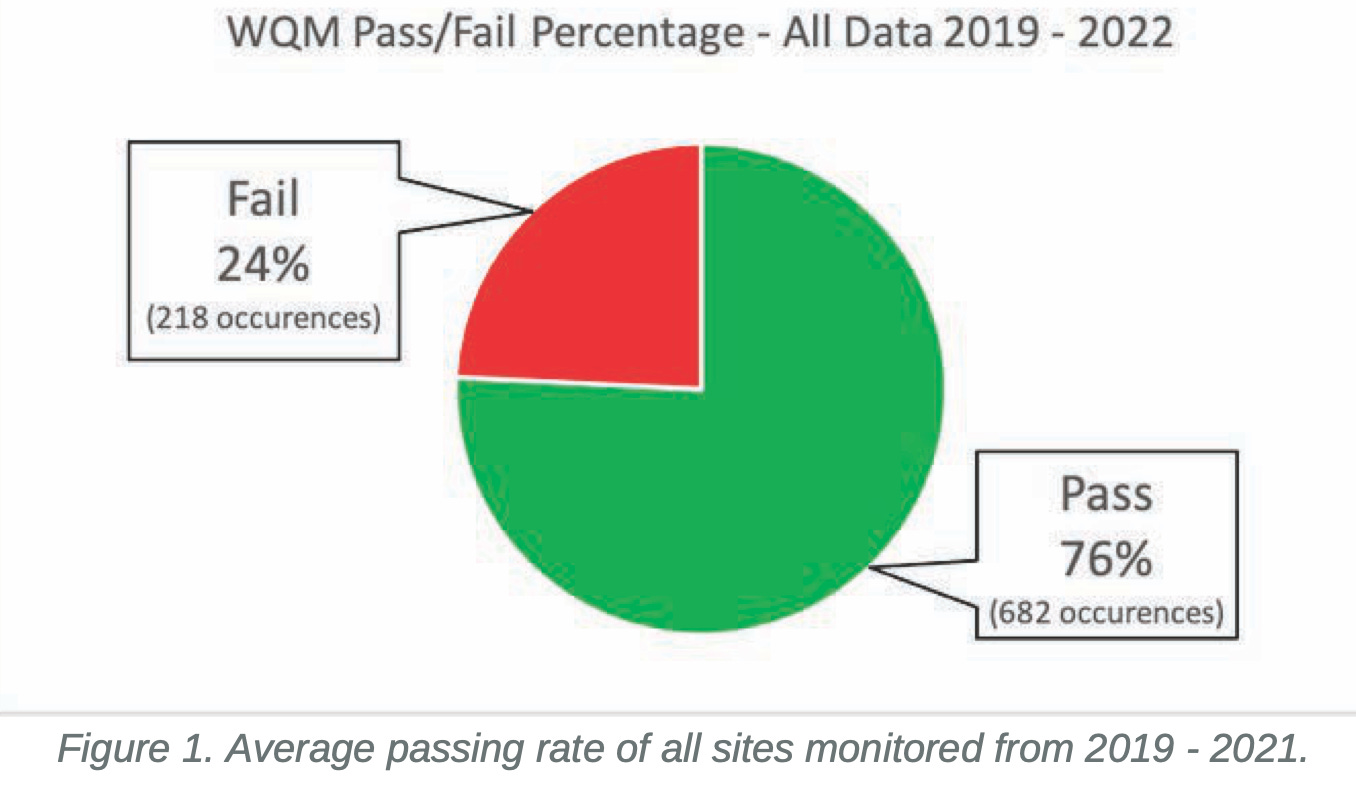

Swimming was banned in the Potomac and Anacostia rivers 50 years ago because they’d become too polluted. But according to the Potomac Riverkeeper Network which monitors and improves water quality, the river is now passing muster 76 percent of the time. Further improvements in water quality are expected in the years to come as Alexandria is building a new pipe that will stop the city from dumping raw sewage into the river, while DC Water continues rolling out new projects to reduce stormwater runoff.

Some of those projects feature large-scale engineering with big pipes, but a lot of the work is smaller scale. If you walk by any of the newer developments in D.C., you’ll probably find landscaping features like this rather than traditional tree boxes. These are called bioswales, and they’re designed to prevent rivers from being damaged by harmful stormwater runoff.

When it rains, the rainwater picks up lots of gunk (a technical term) from the street, and when it runs fast over concrete, all that gunk ends up in the rivers near the city. What you want instead is for the water to be largely absorbed into the ground, the way it would be in a forest, where it can be slowly filtered by the soil. Bioswales create little filtering islands in the middle of the city.

At any rate, the point is that this isn’t some fluke. The river has actually gotten a lot cleaner thanks to a mix of mega- and micro-projects, it’s now mostly swimmable, and there are more projects in the pipeline that should lead to a more swimmable river in the near future. And once the beaches are built, more people will care about water quality and stronger politics around further protections. And importantly, this happy story about the Potomac is pretty typical. As Cari Shane wrote in a great overview for Scientific American back in October, “millions of miles of U.S. rivers have dramatically improved in the half-century after the Clean Water Act, but climate change and other types of pollution still pose threats.”

That stuff after the “but” is obligatory in today’s negativity-obsessed world, but I really do think it’s important for people to know that on the whole, this aspect of the environmental situation has gotten much better. If you’re in your 40s like me, we enjoyed cleaner water than our parents had, and we are bequeathing to our kids water that is cleaner still.

It’s generally difficult to drive attention to positive environmental news, whether it’s cleaner air and water in the United States or the incredible reforestation of Europe.

Sometimes people see partisan or ideological bias in that, but I doubt it’s actually helpful to environmentalism for coverage of environmental issues to be so negative. Encouraging people to associate environmentalism with anxiety and paralysis rather than a can-do spirit doesn’t seem constructive to me. The reason negative attitudes prevail on this topic is the same reason negative attitudes prevail on all topics: the consumers of media like negativity.

Stuart Soroka, Patrick Fournier, and Lilach Nir did an interesting experiment where they conducted “a 17-country, 6-continent experimental study examining psychophysiological reactions to real video news content” that involved measuring people’s skin conductivity as an index of emotional response to different kinds of news. What they found was that across countries, negative news was more engaging. If you want a just-so story about why this is, recall that industrial civilization is very new and widespread economic growth is arguably newer. A hunter-gatherer band’s life is overwhelmingly shaped by downside risk and the imperative of avoiding it — people who pay a lot of attention to threats and bad news are going to win out.

And this is a very general news phenomenon. There was a great study by Bruce Sacerdote, Ranjan Sehgal, and Molly Cook showing that Covid news in 2020 was biased toward bad news. When it came out, a lot of conservatives jumped on that as evidence that the press was out to get Donald Trump. But as I wrote last year, that was an illiteral misreading of the story which included conservative outlets and found that the top outlets found negative stories to emphasize because negative stories were more popular with the audience:

The authors aren’t following the convention where “the media” is taken to exclude incredibly popular and influential media outlets simply because they slant right. Fox News and the New York Post are in the database. What they find is that “the most influential U.S. news sources are outliers in terms of the negative tone of their coronavirus stories and their choices of stories covered,” and “we are unable to explain these patterns using differential political views of their audiences or time patterns in infection rates.”

In other words, conservative and liberal outlets alike emphasized the negative. The intra-media difference is that the biggest and most influential outlets were more negative. And within those outlets, “the most popular stories … have high levels of negativity for all types of articles.”

Like a black fly in your chardonnay, I’d say the coverage of that study was another example of negativity bias at work. The most engaging way to frame the research was “you’re right, conservatives, the press really is out to get you,” rather than the more accurate “objective reality is less dark and threatening than you think.”

With Joe Biden as president, you continue to see this dynamic at work — gasoline prices rising in the first half of 2021 were a much better news story than prices falling in the second half. Journalists who showed almost no interest in the prior 10 years of events in Afghanistan got intensely interested in them for two weeks while the U.S. withdrawal was going badly, then went right back to ignoring the country. The apparent fall in murders in 2022 has been a non-story. Negativity sells.

And I think this plays into the Secret Congress phenomenon in both directions.

On one hand, when a piece of legislation receives a lot of coverage, that coverage is likely to be tilted in a negative direction. It’s simply not possible to have a bill that makes any kind of meaningful changes that doesn’t generate some complaints — either from people who don’t like the changes or else from people who think the changes don’t go far enough. I’ll be forever scarred by the experience of writing about the Affordable Care Act legislative process where it felt like 60 percent of the news was conservatives screaming about death panels and the rest was leftists complaining about the shortcomings of the new system. Far and away the least-covered aspects of the bill — not because of bias but because negativity sells — were millions of people getting Medicaid benefits and millions more getting improvements in the quality of their existing employer-provided plans. Knowledge of the bulk of the bill didn’t become widespread until the ACA repeal debate in 2017 when suddenly “holy shit, they’re trying to take all this stuff away” became a gripping negative story.

And I think the main thing to remember is that in the pre-internet era, Secret Congress was the norm — there just wasn’t that much national news coverage (22 minutes per night on network television), and a lot of that coverage wasn’t political. People got their information through locally focused outlets that mostly weren’t in very competitive markets, so you’d get stories about interesting scandals but not a lot of gripping white-knuckle coverage of actual legislation. That didn’t mean members would always reach agreements on things, but it did mean that if they wanted to reach an agreement, they could do so in relative obscurity and then announce it to the world. Alan Murray and Jeffrey Birnbaum’s 1988 book “Showdown at Gucci Gulch” about the 1986 tax reform is a classic portrait of a contentious legislative battle happening under old media conditions — a knife fight between lobbyists and advocates with minimal engagement from the mass public.

But on the other hand, the actions of Secret Congress tend to languish in obscurity because even though we have much more coverage of national affairs today than we did 30 or 40 years ago, that coverage happens in an intensely competitive environment.

Marjorie Taylor-Green calling someone a “groomer” and then a bunch of people fighting about it is a story that sings more than trying to tell people about a bipartisan deal that increases the amount of habitat available to wild salmon or how the Biden administration is using funds from the bipartisan infrastructure bill to reduce harmful PFAS pollution in drinking water. The news flow you’re exposed to is very disproportionately negative, both because negative stories are more likely to be written but also because the people who you follow on social media are more likely to share them, and also because you yourself are frankly more likely to click on them.

I of course can’t fully exempt myself from the same pattern. I published one good news story about water pollution last year, and I’m publishing a second one today, but it’s not like I’m obsessed with giving you guys week-by-week updates on good news about clean water.

Even more egregiously, back on September 22, I did a post that I thought was interesting about how the Biden administration should commit to refilling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Then when they issued a verbal commitment, I considered doing a post about how that was good but never got around to it. Then I really did come close to doing a post about how verbal commitments weren’t good enough and they needed to make a firmer pledge, but before I could execute on that idea, they actually started doing the refilling. This is great news — the administration sold high on oil, helped to moderate prices, and is now buying low in a way that should continue to support domestic production and hopefully avert an economically harmful boom-bust cycle. But I’m probably not going to do a piece celebrating it. The mainstream media has ignored this important news, and it’s mostly run as a low-key business story that people just don’t seem that interested in. So I’ve stayed away!

But let me just leave you with some more good news.

“Avatar 2: The Way of Water” made me wonder whatever happened to the “save the whales” stuff that was very popular when I was a kid. Apparently, humpback whale populations have rebounded. Same for blue whales. The whale recovery is not complete or totally uniform, but it is real and widespread, and rebounding whale population levels are broadly good news for ocean ecosystems. But nobody talks about this! And to end on my own negative, pessimistic note, I fear that a more competitive information environment is driving more efficient selection for negativity, and that’s just making everyone miserable without achieving anything useful. So I’d encourage everyone to try to be more mindful in their consumption and sharing habits — spread some good news!