The central function of financial innovation seems to be to separate you from your wealth. There are some honorable exceptions – low-cost broad-based index funds surely among them – but those are exceptional. Recently bright people, some with incredibly flexible moral standards, have offered you new opportunities to enrich them. The appeal of each of these hustles is the same: it’s different this time! We’ve got the secret! And we’re willing to let you in on it.

Here are three examples of things you don’t need.

Non-fungible tokens

Or, more accurately, the brilliant digital innovation that follows NFTs on the front pages of every financial website and newsfeed in the world.

NFTs are digital files that, in theory, are capable of being owned, even if others have what appear to be identical copies of them. One advocate explains it this way:

Sales history for this NFT: minted 5/1/2021 and sold 78 times since. Opened at $2,220; sold in Jan. 2022 for $238,015 and Jan. 2023 for $96,779.

NFTs are designed as way for digital files to be secured in a way that ensures ownership and creates scarcity. Like physical art an NFT can be sold but the artist can retain the copyright, or they can offer it to the buyer, or decide the on a percentage of secondary sales an owner can have. (What are NFTs?)

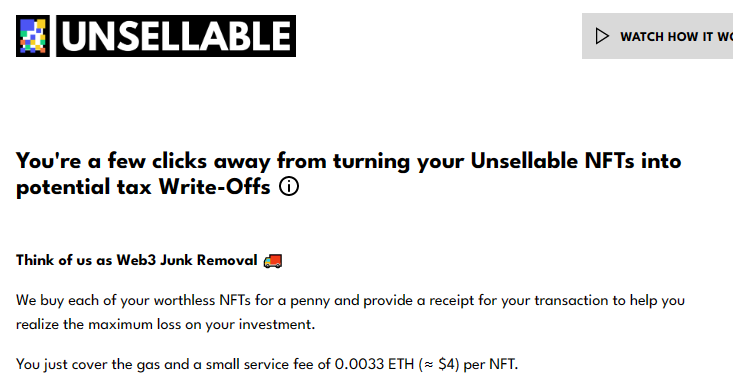

Some continue to sell for tens of thousands of dollars, but so many have crashed so completely (posting “heartbreaking losses in value”) that there’s now a marketplace for dead NFTs. The only bright side of huge investment losses is the ability to use those losses to offset taxable gains elsewhere in your portfolio, thereby reducing your taxes.

Here’s the problem: you can’t realize the loss unless there’s someone who will buy the scrap from you. Enter Unsellable, which is willing to offer you a penny for your NFT if you pay the … well, about 400 times that much to take it off your hands.

NFT advocates remain upbeat about the future of their product, which means they remain upbeat about the prospect of separating credulous investors from their wealth. I would decline the opportunity.

Fine Art for the Masses

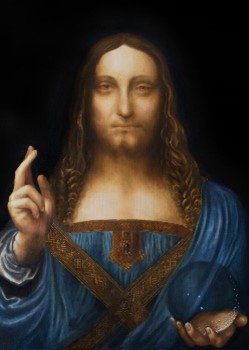

Rich people are different from you and me. They buy stuff we’re not able to. Good stuff. Hedge funds. (Which are mostly disasters.) Farmland. (Which was a great investment before it became a liquid investment class.) Small islands. (Ranging in price from a couple million to a few hundred million, they’re the ultimate illiquid holding.) Fine art. (Salvator Mundi, the da Vinci painting that recently sold for $450 million and which, as it turns out, might not actually be a da Vinci painting. But it looks good over the couch regardless.)

Rich people are different from you and me. They buy stuff we’re not able to. Good stuff. Hedge funds. (Which are mostly disasters.) Farmland. (Which was a great investment before it became a liquid investment class.) Small islands. (Ranging in price from a couple million to a few hundred million, they’re the ultimate illiquid holding.) Fine art. (Salvator Mundi, the da Vinci painting that recently sold for $450 million and which, as it turns out, might not actually be a da Vinci painting. But it looks good over the couch regardless.)

For the latter, at least, there’s now a way for little guys to get a piece of the action. MasterWorks invites you “to join an exclusive community investing in blue-chip art.” (Sidenote: if it was exclusive, they wouldn’t be inviting in the likes of you and me.) They promise a blue-chip portfolio of contemporary art, an asset class that has returned 13.8% over the past 25 years against the S&P 500’s 10.2% return. Art rises in periods of high inflation and is uncorrelated to stocks.

What possible catch might there be? First, the fund charges a 1.5% annual management fee and keeps 20% of profits, the very structure that doomed most hedge funds to mediocrity. Second, there’s no guarantee that you’ll be able to sell your shares on the secondary market at anything like their nominal value; MasterWorks plans to invest in “artists with momentum” and hold their works for 3-10 years. If you need the money sooner, you’re dependent on the secondary market.

Finally, fine art doesn’t actually make much money. RBC Wealth Management published a report on fine art as an investment class. Their conclusion was that (a) it was subject to fads and whim – contemporary art is all the rage now, but in a few years …? – and (b) it has long-term returns below the stock market’s.

Data shows that equities perform better than art over the long term. Over the past 20 years, the Mei Moses World All Art Index posted a compounded annual return of 5.3 percent versus 8.3 percent for the S&P 500 Total Return Index. That gap narrows over the past 50 years: the All Art Index returned 7.9 percent vs. 9.7 percent for the S&P Index.

Similarly, a 2013 Stanford Graduate School of Business study found that art investments don’t substantially improve the risk-return profile of a traditional portfolio. It found that the average annual return of paintings sold at auction from 1972 to 2010 was 3.5 percentage points lower than thought after adjusting for art that sold more frequently and at higher prices.

That is, the performance of “the index” is puffed up by the repeated, escalating sales of just a few super-hot pieces.

Cryptocurrency

Augustana College is located in Rock Island, Illinois, an unassuming river town that was the epicenter of national financial instability in 19th century America. If only we had a nice cryptocurrency exchange, we could repeat the feat – and repeat it for the exact same reason – in the 21st century.

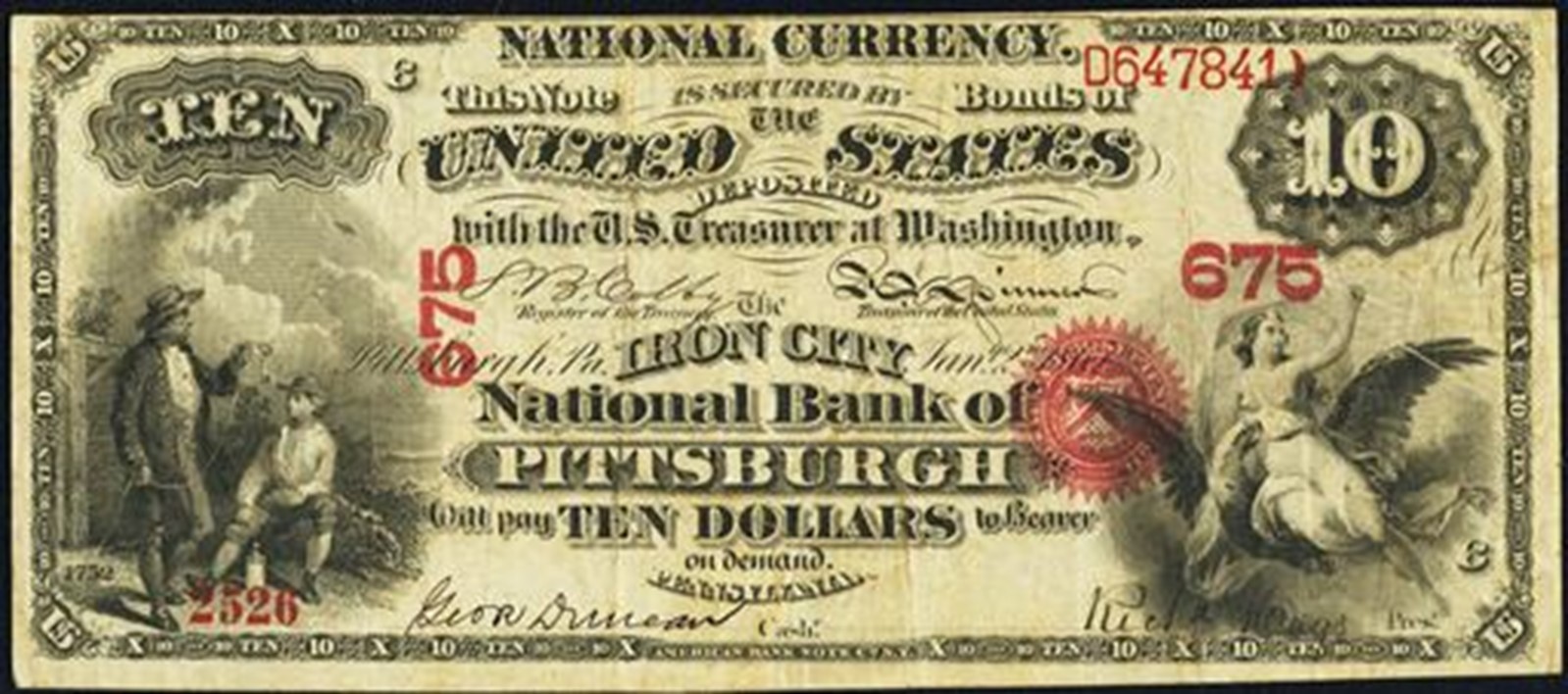

For 150 years of America’s history – from the mid-18th to late 19th century – virtually all of our money was funny money, sketchy scrip that offered more aesthetic than financial appeal. In pre-revolutionary America we were, in theory, using British money … but that meant that we were dependent on the British treasury to mint and ship enough coin to meet our needs. They did not. Early fans of financial engineering found a workaround: banks and businesses would simply print paper money carrying the face value of British coins. In theory, a bank with ₤100 of gold in its vault could issue an equivalent amount of paper pence, ha’pence, tuppence, and thruppence.

The suspicion, of course, was that a bank with rather less than ₤100 of gold might still have issued ₤100 of dodgy scrip, which made people reluctant to accept the money at face value.

The problem escalated after we won independence and didn’t have the vast British treasury to back our currency. (Reportedly, the folks in post-Brexit England have stumbled upon that same epiphany: sometimes, your grand political gestures really come back to bite you in the bum. The Guardian, 12/2/22, offered a sad piece on that slowly dawning realization: “As reality does its work, even those previously sympathetic to the Brexit cause look at it through new eyes. Suddenly the various stats that were once a blur begin to form a pattern.”) Without a national currency backed by a national treasury, money became almost entirely de-fi. That is, the US experienced the “decentralized finance” model celebrated by crypto-evangelists. Hundreds of banks printed their own currency, or, more correctly, hundreds of banks turned to The Rock Island National Bank of Rock Island to print their currency for them.

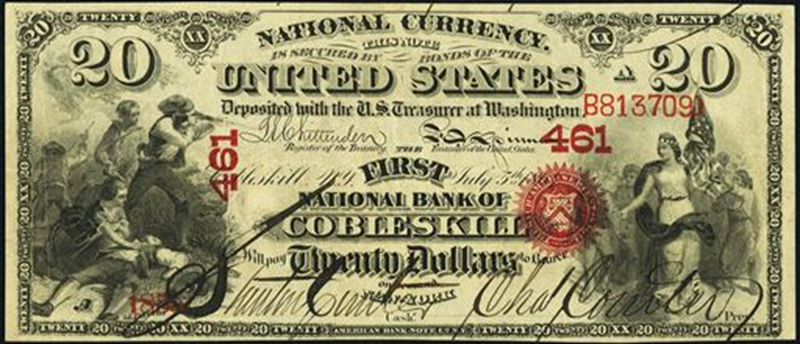

Chip, whose academic career included a stint as one of the Fighting Tigers of Cobleskill, wanted us to share this Rock Island artwork with you as well.

The label “national currency” was … shall we say, aspirational? But then again, so was the term “bank.”

The two problems with private currency are strikingly modern: (1) people didn’t trust it, and (2) people were right not to trust it. A merchant in Cleveland might value a Cobleskill dollar at $.80 even if they didn’t doubt the First National Bank of Cobleskill, while a more skeptical soul in Baltimore might offer just $.60 for it. Since banks were neither insured nor regulated, they failed with some regularity, and their failures often created a contagion across the sector. When a bank failed, all of its currency became worthless, and all of its depositors’ accounts went to zero.

The first major American depression, called the Panic of 1819, lasted until 1821. The Panic of 1837 was the second-longest American depression, lasting roughly six years until 1843, with effects ranging from suicides to bank collapses. The Panic of 1857 triggered a stock market collapse and the liquidation of 900 mercantile firms and lasted until 1859.

The Federal Reserve picks up the summary for the period from the Civil War until the creation of the Federal Reserve:

Between 1863 and 1913, eight banking panics occurred in the money center of Manhattan. The panics in 1884, 1890, 1899, 1901, and 1908 were confined to New York and nearby cities and states. The panics in 1873, 1893, and 1907 spread throughout the nation. Regional panics also struck the midwestern states of Illinois, Minnesota, and Wisconsin in 1896; the mid-Atlantic states of Pennsylvania and Maryland in 1903; and Chicago in 1905. (Banking Panics of the Gilded Age)

We offer this extended history for the benefit of those who think events like the FTX collapse and the evaporation of trillions of value in the cryptocurrency markets are just “growing pains” that will soon pass. The mess created by private money in the 19th century lasted … well, a century and wasn’t resolved until the federal government stepped in and nationalized the issuance of currency, regulated banks, and created deposit insurance. From 2008 through 2015, for example, more than 500 US banks failed, but their depositors were protected by government insurance.

In short, the history of decentralized finance is a history of wild instability and failure. While you might hope “it’s different this time,” you need to be able to offer a concrete reason for why the problems of decentralization can be overcome. The government can’t come riding to your rescue, and some economists strongly argue that it shouldn’t even try: “let crypto burn” is, in their minds, far safer for the economy than letting crypto creep into the real economy.

Here’s the most responsible strategy for folks speculating in cryptocurrencies: in setting up your portfolio, enter the value of your crypto account at zero and keep it there. Crypto criminals stole $2 billion from accounts in 2022; Bitcoin dropped 60% in the year. The crypto universe lost over a trillion, and you’re heir to all of that. So recognize that $50,000 spent on any one of the 10,000 currencies in circulation might well be $50,000 flushed down the drain. If that’s appalling on the face, don’t buy it.

Bottom line

Desperate people do stupid things. Unscrupulous – and sometimes just careless – people help them do it. The most common “stupid thing” is believing in magical solutions to long-standing problems. NFTs were one. Crypto trading is surely another.

Don’t do that.

Don’t become “desperate people.” Live modestly. Invest regularly. Keep down your expenses, both personal (SUVs? Really? To go to the mall?) and portfolio. Gloat more about the money you’ve saved than the money you’ve spent. Plan for modest real returns in a diversified portfolio. Put down your phone. Get outside. Remember how to cook. Celebrate time with family.

Do that.