Why does the United States struggle to create cost-effective rail infrastructure? Why do non-NYC American cities have such a hard time attracting mass transit ridership?

On one level, these are deep and complicated questions. But one thing I want to say to the growing community of people who are interested in them is that American agencies don’t deliver on these goals because this country’s high-level governance constructs don’t say they should deliver on them. Of course you won’t find a grant guideline that specifically says “don’t focus on delivering high ridership at an effective cost.” But wasting money is really, really easy when nobody is specifically telling you not to.

It’s no secret that the California High-Speed Rail Authority is not prioritizing cost-effectiveness; they openly brag about their emphasis on other goals, like small business participation and the creation of good-paying jobs.

Looking at the big picture of California’s high-speed rail fiasco, I don’t think the problem is too many small-business set-asides or excessively generous wages to the construction crew. But slow, expensive projects don’t become unbearably slow and unbearably expensive thanks to one big bad call — it’s the accretion of lots and lots of small bad calls. And that’s what happens with any kind of coordinating principle for their strategy. I can’t promise you that the CAHSR project would have gone great if the authority had a clear mandate to maximize riders per dollar spent from the beginning. But I can tell you that if agencies aren’t explicitly told to prioritize investing in projects that will generate high ridership, you are guaranteed to end up with a poor ratio of dollars spent to riders served.

And I think most people don’t fully appreciate the extent to which ridership is not prioritized by American transit agencies or in the structure of American transit grants.

In his book “Human Transit,” Jarrett Walker introduces the idea of a ridership vs. coverage tradeoff in planning a city’s bus network.

A bus system offers a lot of flexibility, but it comes with high operating costs because each bus needs a driver. So one question that cities face is whether to prioritize frequent service on the most promising routes to maximize ridership or extensive geographic coverage (lots of routes) to maximize the number of people who live near a bus stop. This same tradeoff recurs with the question of how frequently the bus should stop. I, very conveniently, live a block and a half from a bus stop. If that stop were eliminated, I’d have to walk 3.5 blocks instead. I’d obviously prefer the shorter walk, but eliminating half the stops along the route would mean the bus could move faster, which would make it more appealing to riders. And because the bus could move faster, it could run more frequently without hiring more drivers, which would also make it more appealing to riders.

For me personally, keeping the stop closest to my house is optimal, but the people who live by the stop 3.5 blocks away obviously feel the same way about their stop. The principled point, though, is that having the bus stopped every 600 (or even 800) meters rather than every 300 meters would generate higher ridership. The downside is that eliminating specific stops would piss specific people off, and they’d complain.

Walker runs a transit planning consulting business, and he leads a process that illuminates tradeoffs without necessarily prescribing any particular solution.

But I’m a columnist and I’m here to say that it’s a shame that so many cities spend non-trivial sums of money on bus systems that few people ride. Even if the transit agencies had clear mandates to prioritize increasing ridership, they would of course make mistakes — nobody’s judgment is flawless and the United States of America does not have a culture of strong and successful transit agencies. But every agency’s existing personnel are good enough at their jobs to see that some pro-ridership changes are being left on the table due to considerations like “I don’t want to get yelled at at a community meeting.” Telling agencies to prioritize ridership would result in ridership going up, and over time, it would also create an agency culture focused on improving ridership and learning what strategies do and do not work.

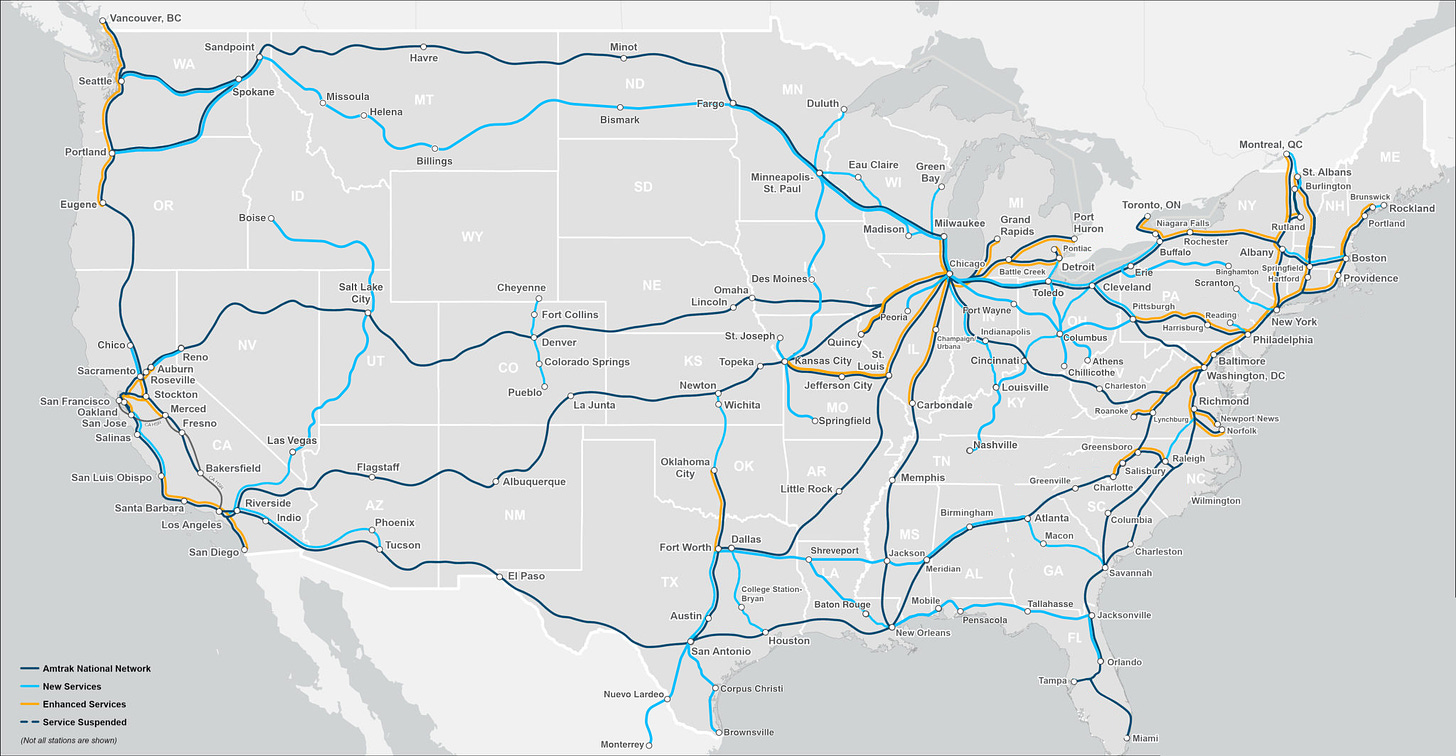

A good illustration of the ridership/coverage tradeoff in practice is offered by the Amtrak wish list map I criticized back in December (“Amtrak Should Build a Good Train”).

Amtrak often puts me in a bad mood, and at the time I wrote that “Amtrak released their new vision for passenger rail expansion in the United States, and I don’t really know what to say except that it sucks.”

A more measured way of putting it is that Amtrak staff and I have different views on the relative importance of ridership vs. coverage. Amtrak does not currently have a strong mandate to prioritize ridership in its planning, and so they don’t prioritize ridership in their planning. There is a lot of scope for reasonable people to disagree about exactly which investments would be the ridership-maximizing ones. But what Amtrak is doing with this map isn’t putting forward a plausible hypothesis about how to maximize ridership. They’re also not putting forward a really stupid hypothesis about how to maximize ridership. They are simply not trying to maximize ridership. And as a result, their plan, if implemented, would not generate very many train riders.

On the Northeast Corridor, meanwhile, Amtrak does have a good number of riders, and the fares are pretty steep even though the Acela falls far short of a European or Asian high-speed rail standard.

One thing I’ve been wondering is whether they shouldn’t eliminate the cafe car from the NEC trainsets. If you replaced the cafe car with an additional passenger car, you could sell more tickets. It’s true that you’d lose some cafe revenue, but the ticket sales would also generate revenue.

Of course people like the cafe car. I like the cafe car! And it’s conceivable that eliminating the cafe car would do so much to tank demand that it would be counterproductive and reduce ridership, even though it would increase capacity. But Amtrak doesn’t have some model that says “eliminating cafe cars to increase capacity would backfire by tanking demand for rail travel.” It’s just that they don’t have a mandate to maximize ridership, so they don’t ask questions like “could we increase ridership by eliminating cafe cars?” It’s obvious that if you eliminated them people would complain, so absent a clear mandate to guide change, it doesn’t happen.

I’m a big fan of the work of the Transit Cost Project, a small team at the NYU Marron Institute that’s produced some in-depth reports on why American transit projects seem so comparatively expensive.

But the more work they do, the clearer it seems to me that the big meta-reason is just that nobody is trying to make the projects cost-effective. They had a great case study out of Boston where the Green Line Extension went so far over budget that it got canceled and then re-launched in a cheaper way. One key to reducing costs was eliminating plans to build large custom stations and going with simple bare-bones ones instead. So why did they propose the large stations in the first place? I have no idea. The existing and well-used Green Line stations are incredibly bare-bones. There was nothing in the local transit tradition to suggest that the extension needed large grand ones. All else being equal, people might prefer a really grand station to a bare-bones one, but there was no MBTA modeling that claimed this expenditure would make the system dramatically more appealing. They simply weren’t asking the question “what will the ridership impact of this spending be?” because American transit agencies aren’t in the habit of asking those questions.

Here’s Alon Levy, one of the main movers behind the Transit Cost Project, describing some of the sources of expense in New York’s Second Avenue Subway project. As you can see, the basic answer to the question “why did this cost so much?” is that at every turn the MTA chose to do expensive things:

Another $11 million is surplus extraction at a single park, the Marx Brothers Playground. As is common for subway projects around the world, the New York MTA used neighborhood parks to stage station entrances where appropriate. Normally, this is free. However, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation viewed this as a great opportunity to get other people’s money; the MTA had to pay NYC Parks $11 million to use one section of the playground, which the latter agency viewed as a great success in getting money. Neither agency viewed the process as contentious; it just cost money.

But both of these examples are eclipsed by the choice of construction method for the stations. Again in order to be a good neighbor, the MTA decided to mine two of the project’s three stations, instead of opening up Second Avenue to build cut-and-cover digs. Mined stations cost extra, according to people we’ve spoken to at a number of agencies; in New York, the best benchmark is that these two stations cost the same as cut-and-cover 96th Street, a nearly 50% longer dig.

Moreover, the stations were built oversize, for reasons that largely come from planner laziness. The operating side of the subway, New York City Transit, demanded extravagant back-of-the-house function spaces, with each team having its own rooms, rather than the shared rooms typical of older stations or of subway digs in more frugal countries. The spaces were then placed to the front and back of the platform, enlarging the digs; the more conventional place for such spaces is above the platform, where there is room between the deep construction level and the street.

Thanks to the work that Alon and other outsiders have done on these problems, a growing number of people in the federal government have begun prodding American agencies about their costs. But what agencies tend to hear when they get these questions is an allegation that they are overpaying for things. So to the accusation that they spent too much on SAS stations, the MTA basically argues that on a per cubic foot of blasting basis, what they pay is reasonable and largely reflects the fact that the United States is a high-wage country. Similarly, the MBTA’s grand stations on the Green Line Extension weren’t overpriced in the sense that you could have built the exact same thing for much less money. They were overpriced in the sense that the amount of money spent on them was disproportionate to their actual utility.

But agencies don’t make smart cost/benefit decisions in part because they don’t have a clear mandate about what’s supposed to go in the denominator of that ratio.

The reason agencies don’t have a single mandate to promote ridership is, of course, that there are other things that people want to consider — things like environmental benefits, racial and socioeconomic equity, and economic development.

But I think that in the 21st-century United States of America, a basic ridership goal is a decent proxy for all that other stuff. This is not necessarily the case in all places. India has 59 cars per 1000 people, and even a gigantic city like Mumbai only has three operational metro lines (they are building more). In other words, a very broad swathe of the Indian population has neither a car nor access to quality mass transit, which means it’s plausible that many potential mass transit projects would attract high ridership without serving the most marginalized communities. The United States just isn’t like that. The carless Americans who also don’t live near good transit are a very marginalized group, so a ridership goal naturally has a thumb on the scale in favor of finding concentrations of low-income people to serve. But beyond that, even if a specific high-ridership project doesn’t have a particularly low-income service population, building functional mass transit networks is good egalitarian public policy, and if you pursue high ridership goals, you will create functional networks.

The same is true for environmental and economic development goals. You can create jury-rigged examples of a bus route that displaces bike riders and has no emissions benefit or something. But if you look at the Chicago/D.C./Boston/San Francisco/Philadelphia tier of American transit cities, it’s just clearly the case that any substantial increase in ridership would mean lower emissions. And you could try to claim that Amtrak’s plan for a slow, infrequent train between Cleveland and Columbus will promote some important economic development goal, but ask yourself: how that could possibly be the case if nobody rides the train?

Now again, I’m happy to concede that across the entire possibility space, you could imagine a situation in which one route maximizes ridership but a slightly different version maximizes economic development goals or equity goals or environmental goals. But those divergences would in practice be either pretty rare or pretty small. On the whole, a significant increase in transit ridership would be egalitarian and good for sustainability and economic development. And importantly, telling agencies to try to hit a half-dozen different goals — equity benefits, environmental benefits, economic development benefits, but also job-creation benefits, stuff for small businesses, improvements to the Marx Brothers Playground, etc. — doesn’t ensure that all those things will be done simultaneously. What it ensures is that, with no principled way to evaluate projects or say no to things, costs explode.

Simplicity is often a virtue. Building high ridership projects isn’t the only conceivable goal for transportation infrastructure, but in meeting that goal, I think transit agencies would make a lot of progress on other goals as well.

But most importantly, by setting themselves a clear and simple task — spend money on things that people will use — they stand a chance of actually achieving the goal. Should we build a subway tunnel under Second Avenue? Yes, it seems like a lot of people would use that even if it was expensive to build. But should we blast the stations or do cut-and-cover? Blasting would cost a lot more and has no ridership benefit. The case for blasting is the neighbors would like it better. And it’s not that we should necessarily be indifferent to the neighbors, but in this case, we are building them the gift of a brand new subway line. If they insist on doing it in a more costly way, that makes the proposal less cost-effective and reduces the odds that it will pop to the top of the list. But say we do settle on blasting; do we blast bigger stations or smaller ones? Well, the stations shouldn’t be tiny to the point of imperiling ridership. But we shouldn’t spend money on features that don’t have commensurate benefits in terms of making people want to use the train.

This wouldn’t automatically fix all problems; agencies that don’t have experience building cost-effective projects would still struggle. But people are very capable of learning.

At the end of the day, though, things don’t change for no reason and people don’t make decisions that risk getting them yelled at during community meetings just because they read some blogs. American agencies don’t prioritize ridership in their decision-making, and the grant programs that sustain them don’t tell them to prioritize ridership. Instead, everyone works with very complicated multi-criteria processes that sound nice but in practice are clearly failing. It’s time to try something else.