Last week, I discussed the December CPI print; it showed further evidence that inflation is coming down substantially. But I had to point out this was not because of the Fed, but despite their actions. If anything, they are making price increases worse. In particular, they are driving prices higher in the rental market.

Today, the Producer Price Index and Consumer Retail Sales both showed the economy is decelerating and not on an inflation-adjusted basis. Consumers have finally stopped paying up for goods, as their “revenge spending/travel” seems to have run its course (for now).

As our discussions last week suggested, most of the falloff in Goods inflation began in the middle of 2022; elevated prices in wages, autos, housing, and energy are primarily driven by a lack of workers, a shortage of semiconductors, and a tiny supply of single-family homes (elevated energy prices are war related).

The narrative I have been spinning is that the pandemic-related surge in demand overwhelmed supply constraints and that lead to price spikes. The New York Fed found that supply constraints were responsible for 40% of inflation. As the balance between consumer demand and supply normalized, price changes returned to normal. Rates, not coincidentally, were not the driver of falling CPI.

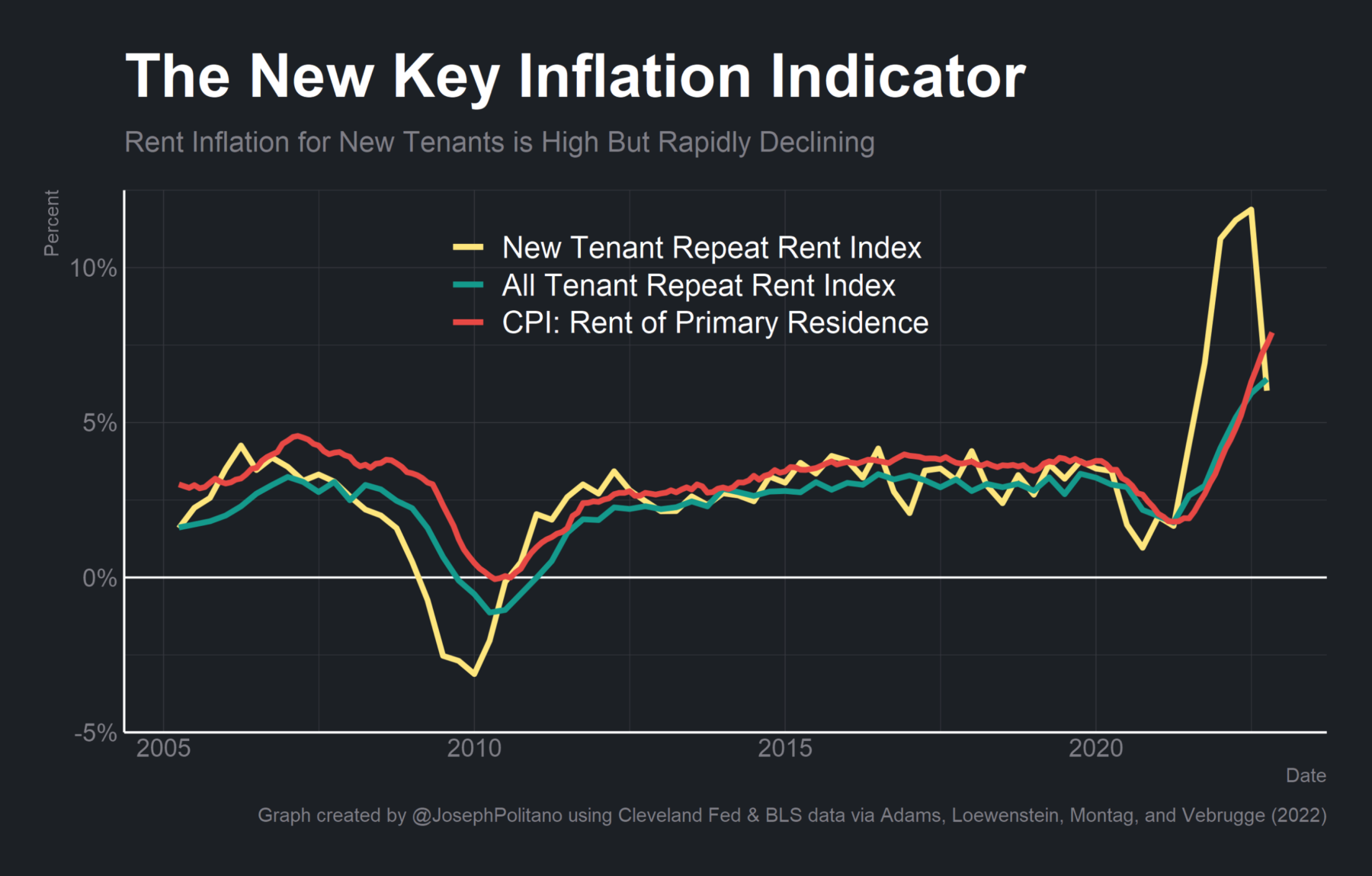

Today, the services side of inflation is primarily driven by apartment rentals (“Owners Equivalent Rent” in the CPI model). We discussed in October how higher FOMC rates drove mortgage rates. Today, the average 30-year mortgage is 6.23% – a 4-month low, but double what rates were a year ago.

Rates + the pre-pandemic lack of single-family homes + Covid home purchasing frenzy = a huge shortfall in supply. This combination has sent people who would typically be home buyers here into being rentals, sending prices surging.

I believe there are two steps the Fed can take to address this issue:

-Fix models that rely on Owner’s Equivalent Rent;

-Freeze — or Lower — Intersest Rates

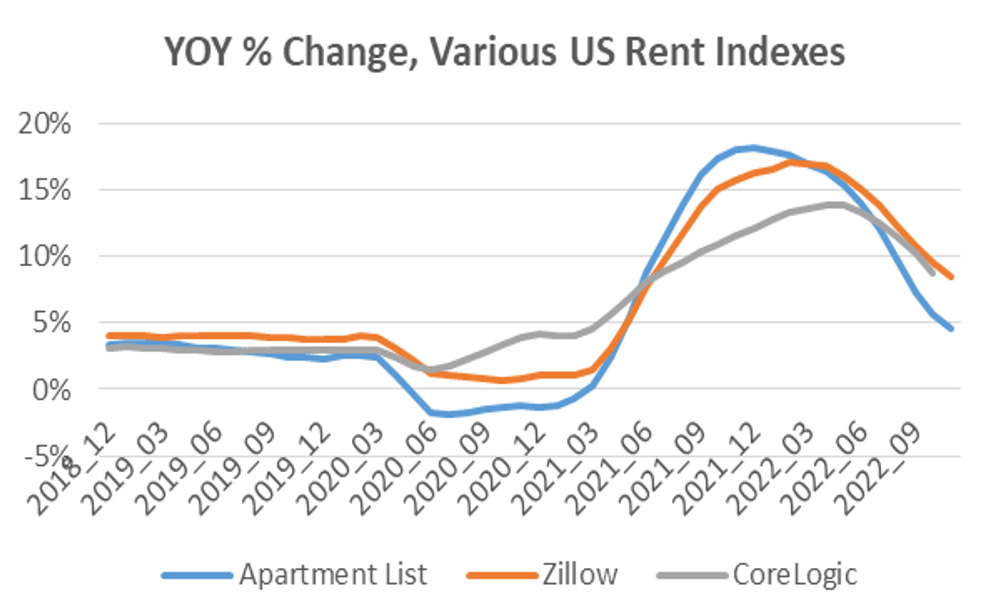

Start with the models: As the Calculated Risk chart below shows, other measures of rental prices have shown prices are decelerating. OER is assembled in a way that seems to exacerbate the lag between what is happening in the real estate market and what the BLS models show. A data-dependent central bank surely should be working off of the latest available information.

BLS periodically updates its CPI models; they seem to be aware of the issues with OER. But this does not mean the Fed should inflict pain on millions of people (especially those earning at or below median wages) because they are waiting for an update to an economic model.

Powell & Co.’s second step should be to recognize how they are impacting apartment prices. It’s pretty obvious that chasing away a substantial percentage of home buyers — especially first-time buyers — is only going to create more rental demand, sending those prices higher.

Rate increases are a blunt tool, especially when we consider the aberrational circumstances surrounding the past 3 years. Central Bankers would do well to add a little nuance to their policies. Otherwise, they are going to unnecessarily cause economic damage in their belated attempts to lower inflation.

There is not a lot the Fed can do to increase the number of workers, create more single-family homes, end the Russian war in Ukraine, produce more semiconductors, or untangle snarled supply chains. At the very least, they can stop making apartment rentals more expensive…

Previously:

Inflation Comes Down Despite the Fed (January 12, 2023)

Supply Chain Is 40% of Inflation (November 17, 2022)

Behind the Curve, Part V (November 3, 2022)

Why Is the Fed Always Late to the Party? (October 7, 2022)

How the Fed Causes (Model) Inflation (October 25, 2022)

Why Aren’t There Enough Workers? (December 9, 2022)

How Everybody Miscalculated Housing Demand (July 29, 2021)