The BBC intends to

commission reviews on impartiality in various subject areas, and last

week it published its first on

fiscal policy (taxes, spending, government debt and

all that) written by Michael Blastland and Andrew Dilnot. I think

it’s a good report, and the BBC’s coverage in this area would be

a lot better if its suggestions were widely followed. As I coined the term mediamacro to signify the disconnect between macroeconomic knowledge and what was said in the media, I very much welcome this attempt to bridge that gap. However at the

end I want to note two fundamental problems, one of which at least

the authors could not avoid.

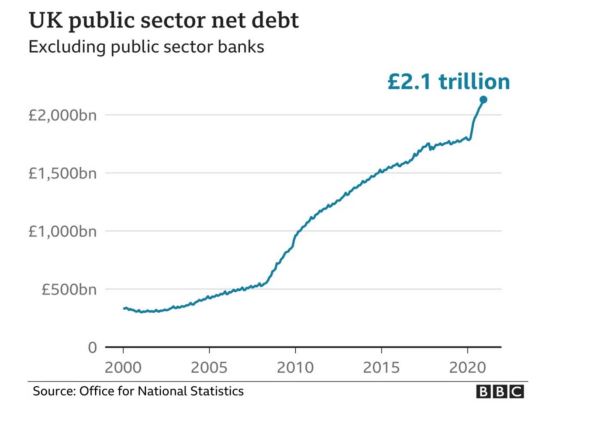

The report starts

brilliantly with a chart published by the BBC. Although this just plots ONS data, it is biased. Why?

For most people this

chart looks scary, and there is a danger that this is why it was

presented this way. (Laziness may be another reason.) I and most

other economists would say it is highly misleading because debt is

not normalised (divided by some other economic variable, like GDP).

The way the report describes this is that “it brings a high risk to

impartiality and can lead to the appearance of bias”.

Both economists and

the report are right. If you look at the path over time of debt

divided by GDP (as you should) the picture looks a lot less scary, especially if you

take the series back to just after WWII. By presenting this chart,

the BBC was both misleading and biased, even though it was just

presenting data. The report then goes on to criticise more general

alarmism in reporting about government debt. In reporting there is

too often a presumption that debt is bad, and more debt is always

worse. I would just say that presumption is wrong, while the report

would say that views differ, and that to assume its bad is therefore

biased. [1]

To say that the

government is not like a household and therefore household analogies

should never be used is too strong. Sometimes these analogies can be

useful and helpful for audiences. However at other times they can be

terribly misleading, as my blog pointed out many times during the

austerity period. The report rightly says that “it helps to know

that household analogies are dangerous territory, intensely

contested, and can easily mislead.”

Some may say that

using household analogies represents deliberate political bias by

journalists. The report suggests, and I think this is correct, that

it normally represents ignorance. Most political reporters are not

economists, and the breadth of what they cover means that they end up

being experts in little except who is up and who is down in a

political pecking order. It is worth quoting the report on this:

“It’s clear to

us that political perspectives can be partial, neglecting others.

Political journalists can likewise miss or misunderstand or

underweight economic perspectives. We could simply say that’s why

the BBC has other specialists. But if they’re all bound from the

outset to work within a political frame that shapes the choice of

subjects, interviewees, the running order, the line of questioning

and the shape of the story – perhaps squeezing it into binary

politics – how much can other specialists really exercise influential

judgement? A risk is the BBC overlooks interests that lack current

political salience.”

I think the report

isolates a key problem here, and one whose scope goes well beyond

fiscal issues, but it ducks exploring the fundamental reasons for it.

Its recommendation here is really little more than ‘must try

harder’. As I have suggested elsewhere, the problem lies in an

explicit hierarchy which puts Westminster politics in the most narrow

sense (who is up, who is down) above all else. To take a very recent

example, the government can only get away with claiming that higher

public sector pay will increase inflation because it knows that

political journalists won’t subject the claim to the ridicule it

deserves because these journalists don’t know it’s ridiculous (HT Tim Bale).

This may seem like

bias. Journalists will too often adopt a political frame provided by

the government because they are ignorant that other frames are

possible. The report is rightly critical of reporting that says, for

example, that a rising deficit means the government will have to cut

spending. What it should do is report that a rising deficit will mean

the government will say it has to cut spending, but other choices

like higher taxes or accepting higher borrowing are possible.

As the reports says:

“Governments often claim their choices are acts of necessity; this

does not make them so.” It also points out that reference to the

government’s fiscal rules can invoke similar dangers, because

the rules are themselves contestable and contested. They may be rules

for the government (although for this government frequently

broken and revised), but not rules for society.

More generally the

report talks about the dangers of journalists projecting a consensus

where none exists except perhaps between the two main parties. It

suggests that

“in economics we

think there’s a case for a small shift in the balance of perceived

risks towards more breadth of expert view. We mentioned a well-known

academic who felt his views on debt were largely ignored during

austerity, and who many might now say had a reasonable argument.”

That could be me, as

I did give evidence to the report, but of course it could have been

countless other economists. I personally would say we need much more

than a small shift towards more expert views.

Now to the two elephants. The report doesn’t

say that over the 2009-16 period the

BBC, along with the rest of the broadcast media, made a colossal

mistake in adopting the line that reducing the deficit

was the most important priority for fiscal policy. This was not at first a failure of treating a political consensus as an

economic one: initially Labour opposed the extent of austerity. It is

possible to argue that this mistake had profound consequences, not

only in pushing Labour towards the government’s position, but also

in influencing the 2015 election, and after 2015 in creating the

space for Corbyn to become Labour leader. Whatever you think of those

consequences, it all stemmed from the broadcast media getting the

economics completely wrong.

That is the first

elephant in the room that the report fails to confront head on. It is

important because the media’s near consensus that austerity was

necessary was not just the result of ignorance on the part of

political journalists. If you read Mike

Berry’s book, for example, it is clear that the

austerity consensus included the economic journalists at the time. As

I have pointed out in my

own book, the evidence suggests the majority of

academic economists always disagreed with austerity, and by 2015 that

majority was a consensus. The reason for this disconnect between

economic journalists and state of the art knowledge over the

austerity period is not addressed in the report.

Why did most economic journalists adopt the media consensus that reducing the deficit was more important than ensuring a swift recovery from the deepest recession since WWII? I have written about the influence of economists employed by City firms in my book, and I have also written more recently (at the time I talked to the authors of this report) about the origins of mediamacro. But the fact remains that, even after publishing my blog, none of the economic journalists working for the broadcast media ever contacted me about austerity. [2] That either suggests huge arrogance by journalists about their own intellectual abilities, or more probably it reflects that getting the economics right was both not important and also possibly dangerous for the journalists concerned. [3]

The second elephant is one which the report could not avoid,

and that is in adopting impartiality as the overriding frame of

reference. I have written about this in detail here,

but its biggest problem is that the truth becomes of secondary importance.

Impartiality seems to be defined in terms of what people think, even if what

they think is just wrong. So under impartiality, anti-vaxxers

should get some air-time, as should climate change deniers.

To see how

disastrous this impartiality framework is, you only need to look at

the Brexit referendum. The BBC, following impartiality, gave equal

airtime to both sides whenever the economic consequences were discussed, and drew back from calling out obvious

lies that largely came from the Leave side. On the economics of Brexit

there was as close to a consensus among academic economists as you will ever

get, and the BBC mostly ignored it. Arguably the consequences of

that failure have been with us ever since, because the academic consensus was right. [4]

So it is quite

plausible that two major errors in the way the BBC has treated

economic issues have had a crucial role in political developments

since 2010, with the terrible consequences we see today. If the BBC

follows the report’s recommendations its reporting will certainly

improve, but it remains only a first step to correcting the

disastrous errors that the BBC and others made over the last fourteen

years.

[1] There is a way

of making this point, popular among some, which carries risk. The

argument is that government debt represents someone else’s wealth,

and we normally think wealth going up is a good thing, not a bad

thing. All true, but most people do not own government debt directly,

and even those who own it indirectly may be unaware of that, so it

remains the case for these people that government debt is a potential

liability and not an asset.

[2] Why should they have contacted me? Because at the time I was one of a small number of senior UK academics working on monetary/fiscal interaction, and austerity was all about monetary/fiscal interaction. I had a track record of advising the Bank of England and the Treasury, and on major policy issues my advice had been right.

[3] If you think dangerous is too strong a word, can I remind you what happened to Stephanie Flanders when she made the obvious point that strong employment growth coupled with weak output growth was problematic because it implied weak productivity growth. I’m also fond of this post I wrote on that.

[4] I used to think the media making political impartiality more important than knowledge was peculiar to economics, but the pandemic showed it was not.