I am always fascinated when seemingly random sources converge on the same concept. The current convergence involved some research I was doing centered on Dunning Kruger, Vanguard’s Tim Buckley, my partner Josh’s AI/ChatGPT post, and the general state of the market. It’s like a real-time version of “The Blind Men and the Elephant,” by John Godfrey Saxe.

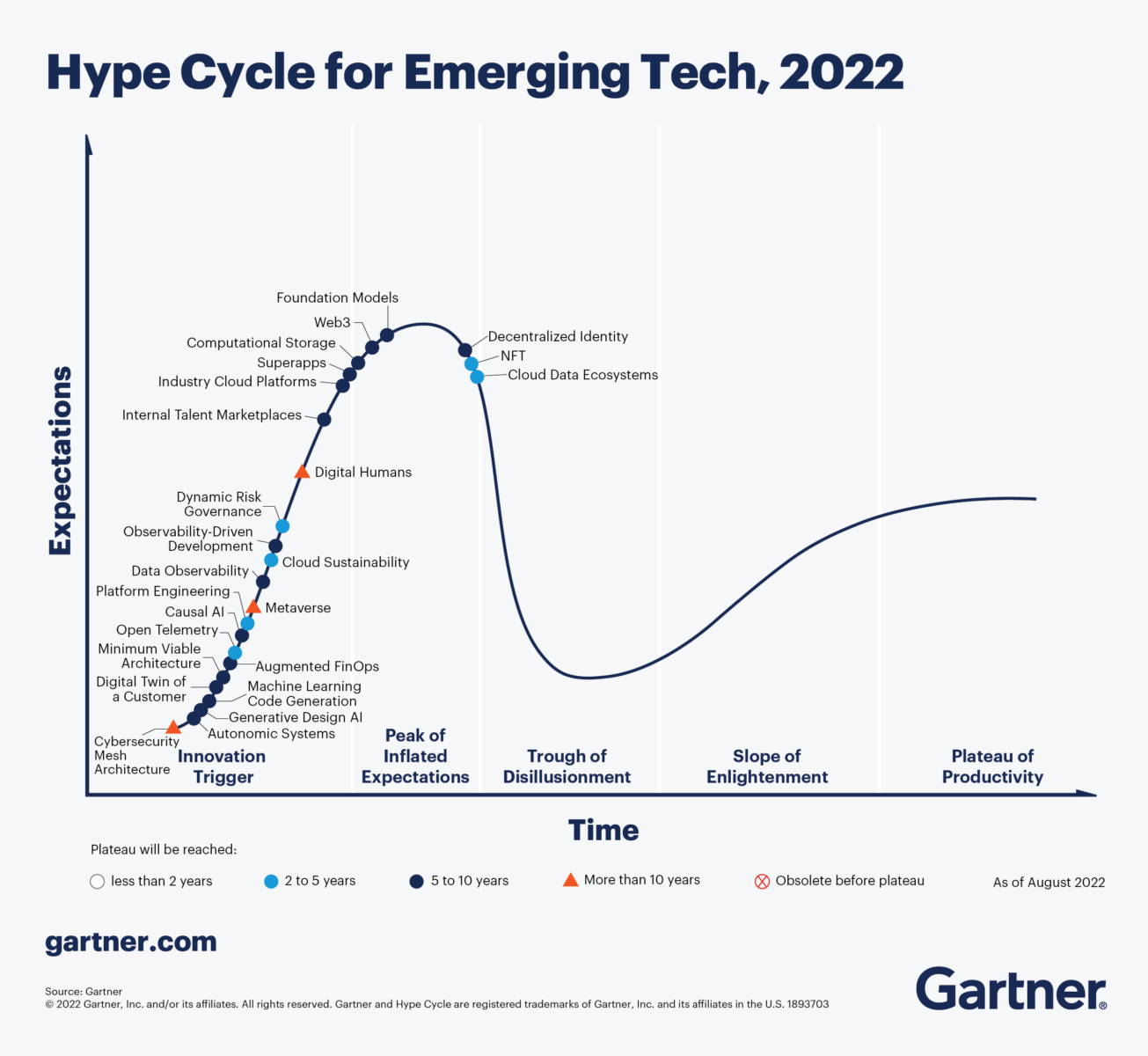

In our conversation at ETF Exchange, Buckley talked about what he learned from the errors he made early in his career: “In the 1990s, the internet was a huge innovation that was going to change how we lived and worked – but that did not mean it could not also be a tremendous bubble.” He referenced the Gartner Hype Cycle (chart at top) as an example.

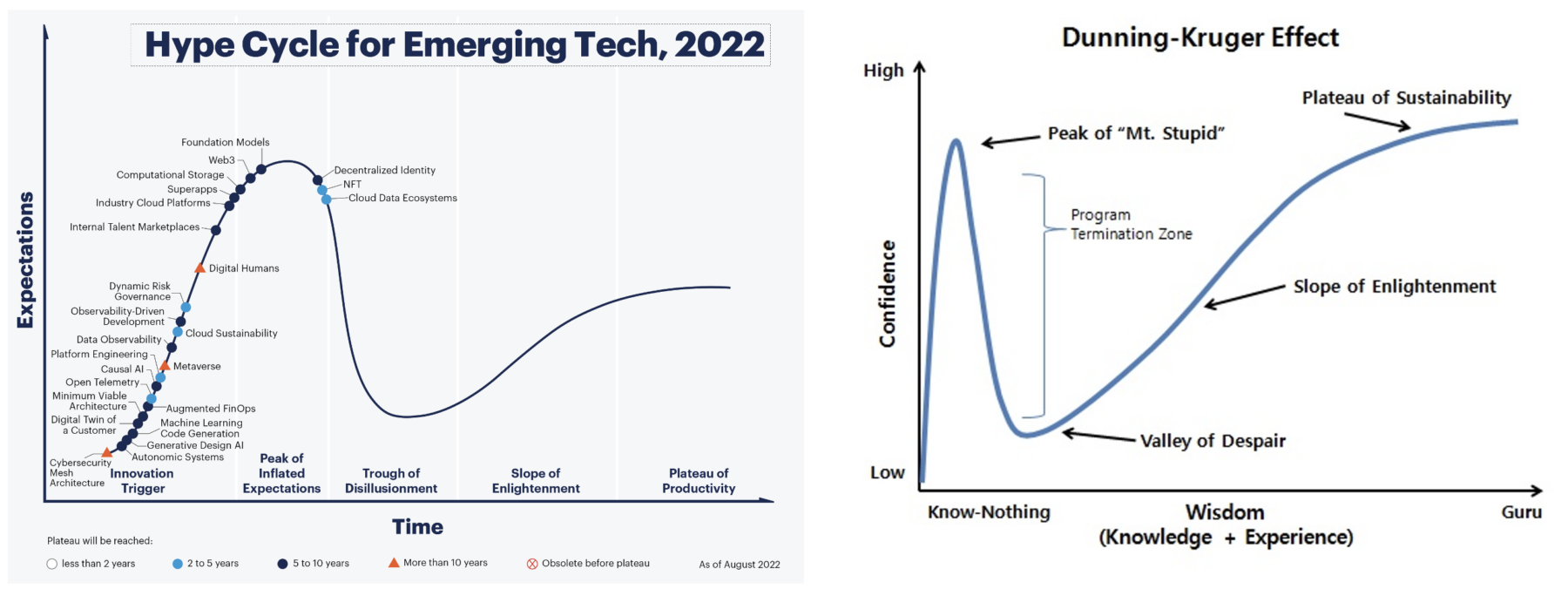

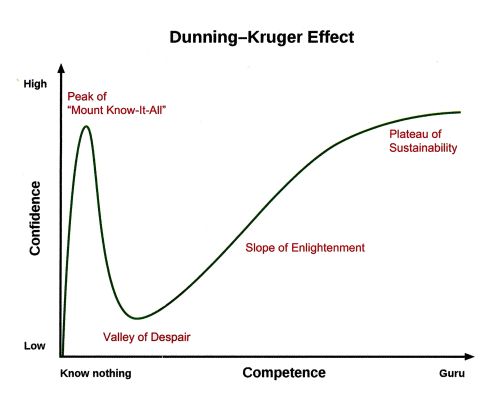

Josh’s post got me thinking along the same lines. I could not help but notice that the Gartner Hype Cycle looks remarkably similar to the Dunning Kruger effect. If you consider the two, it is unsurprising. I suspect the nexus between them is based on subject matter expertise.

Perhaps it is the “void” of experts in each that more accurately describes the connection.

Whenever a truly new and innovative technology comes along, there are a tiny number of people who have actual expertise in the space. This creates a void which is filled by opportunists who have identified a less competitive, crowded field. And so, lots of people stake their claim in the new frontier. A land rush mentality can easily develop around the new idea.

In many of the newest new things, a serious expertise is needed: Think fiber optics, software, or biotech.1 Often, the minimum required expertise is substantial and daunting, and this tends to dampen the enthusiasm of rank amateurs.

But other such new worlds were wide open. The 49ers gold rush appeared to require nothing more than a willingness to go out West and work hard. The reality was something else. Consider all of the new entrants who piled into telegraphs, railroads, radio, automobiles, dotcoms, computers and crypto. Michael Dell famously sold PCs out of his dorm room; in the early parts of the 20th century, there were endless new car companies.

Where the DK/GHC really overlap is when a new product has a low hurdle rate. I was always amused at the “expert” pitches I got from the new Social Media wizards who had few followers on Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok.2 And what precisely was your expertise in Bitcoin that allows you to predict a price of $200,000, $500k, or even a million dollars? Overconfidence leads many things to appear to be simple but are actually hard.

Nature and capitalism both despise a vacuum.

When a truly novel situation comes along, it creates a heady mix of excitement and money-making possibilities. Few experts are known to the public and the media. Hence, the wide-open field with much less competition leads to a natural desire to jump in and grab those profits.

I always wonder how much of our cognitive foibles are evolutionary baggage. Unwarranted self-confidence worked wonders on the savannah for the species hunting mammoths, even if everyone was not fortunate enough to survive the hunt and return to the cave safely. But the group, as a whole benefitted.

What worked a million years ago is not typically what works in the capital markets today…

See also:

The AI Bubble of 2023 (Reformed Broker)

Previously:

Simple, But Hard (January 30, 2023)

Masters in Business Live With Vanguard’s Tim Buckley (February 6, 2023)

__________

1. The obvious theory as to why Theranos crashed and burned, was it was fatally flawed from its inception. By relying on the vision of a person completely lacking in any skills or expertise (or even a background) involving blood technology.

2. See footnote 2, here.

The first rule of Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re in Dunning-Kruger club. pic.twitter.com/1k2slcGXYi

— Barry Ritholtz (@ritholtz) August 25, 2022

What’s New in the 2022 Gartner Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies