This week, the British Broadcasting Commission (BBC) released the results of an independent review into its coverage of economic matters – Review of the impartiality of BBC coverage of taxation, public spending, government borrowing and debt – which was completed in November 2022. The problem is that the Investigation conducted by this Review, while interesting and providing some good analysis, misses the overall source of the bias that our public broadcasters have fallen into. The problem is not that they might be favouring political positions of one party or another. Rather, the implicit framing and language they use to discuss economic matters is largely flawed itself. And the journalists who uncritically use these concepts and terms just perpetuate the fiction and mislead their audiences.

The Review was commissioned by the broadcaster in April 2022 and was conducted by Michael Blastland, who is a writer and former BBC current affairs presenter and Andrew Dilnot, who is an economist and was formerly the Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the UK Statistics Authority.

So mainstream economics voices conducting a review into mainstream coverage, which I don’t think is a good start.

In context, the BBC is like a lot of public broadcasters, and the ABC is an exemplar in this regard.

An exemplar of bias in the coverage of economic matters and particularly in terms of the way understandings (or fictions) relating to the capacities of currency-issuing governments are transmitted to their readership, watchers and listeners.

The way in which these public broadcasters have bowed to neoliberal political pressure and constrained the platform they give to so-called experts, while excluding others who actually know things about these matters has become very notable over the last few decades.

There is massive political interference at the top level of these institutions which rely, largely on public funding either directly (in the case of the ABC, or indirectly via the licence fee in the case of BBC) for their on-going operations.

I have first-hand experience of this.

Previously, for example, the ABC would get independent academic researchers to provide commentary on economic matters.

Then, around the 2000s, that changed and progressively commercial bank economists would be wheeled in for daily financial updates, replete with their company logos in the background.

The ABC didn’t tell their audience that these ‘experts’ had vested interests in the sorts of things they were commenting about – for example, interest rate speculation.

So the commercial banks were given the platform to push their profit ambitions masquerading as informed reporting.

A senior ABC official told me once that the reason they made this shift was because it was hard getting into contact with academics and the bank economists were always there and willing.

Of course they were.

But the rationale also paled thin given that in the time I am talking about we all have had mobile phones and can be contacted 24/7 basically.

I know that various government officials at various times have pressured various broadcasters who invite me to comment occassionally (less than they used to) to stop having my voice heard.

So it was interesting to read the ‘independent report’ into the BBC.

They enquiry concluded that:

… significant interests and perspectives on tax, public spending, government borrowing and debt could be better served by BBC output and were not protected by a simpler model of political impartiality. We would not call this bias … We did not find evidence of wilful bias …

If it is not bias then what is it?

For a person locked into a particular paradigm in economics, like the mainstream New Keynesian macro approach, it would be difficult for them to detect bias anyway.

The Review was seeing bias in terms of whether it supported Conservative or Labour viewpoints – that is there send of ‘impartiality’ – “to favour particular political positions” – whereas I adopt a much broader concept of bias.

In my reckoning, economics itself, the theoretical and empirical frameworks used etc, is a contested field.

Using terms such as ‘budget’ in reference to government fiscal positions is biased.

How?

While in general usage (from the Oxford Dictionary), the term ‘budget’ refers to some “estimate of income and expenditure for a set period of time”, if you consult the Dictionary you will see the qualify that definition with an example: “keep within the household budget” (Source).

Why is that problematic?

It is because the focus of understanding shifts to our experiences in running our own financial affairs, which provide no knowledge that would allow us to understand the fiscal capacities of the currency-issuing government.

We are financially constrained in our spending choices.

The currency-issuing government is not.

So the bias enters not because commentary favours some political position – Conservative or Labour or whatever – but is intrinsically built into the concepts deployed in the commentary, the tools used to assembling reports, and the language used in those reports.

There is also clear political bias that is possible.

But the bias I am referring to goes much deeper than that.

It is related to the uncritical acceptance of metaphors, language, concepts etc that are in themselves loaded in an ideological sense.

Marxists used to complain about the ‘bias’ in national accounting structures.

Why?

Because the way in which national statisticians assembled the National Income and Product Accounts under international conventions exclude statistical estimates of ‘surplus value’ for example, which is a central concept in Marxian analysis.

That is an example of the hidden or unstated bias in the way we report things which transcends merely supporting one political party more than another.

This sort of implicit bias manifests in who the broadcasters give the platform to, how they express the information, and more.

The term ‘wilful’ is interesting.

I thought about my readings of John Locke when I studied philosophy, in particular his treatment of consent.

Accordingly, we are considered to become part of some society with attendant obligations not usually by directly stating so but by our tacit actions.

He considered the fact that an individual walks along a road provided by the government means they are consenting to the legitimacy of that government and all that goes with that.

‘Wilful’ usually means some deliberate or intentional act.

But if a person is using the national broadscasting platform and the coverage that provides to report on particular specialist topics such as fiscal or economic matters, then they are intentionally holding themselves out as qualified to do so and they present to their audiences in that way.

If, in fact, they are not qualified to do so, or are using the language and constructs of only one economics paradigm, without acknowledging the contested nature of the topic within the academy, then in my view they are wilful, even if only tacitly (through ignorance).

The BBC Report found that:

… too many journalists lack understanding of basic economics or lack confidence reporting it.

I have identified the trend where reporters or presenters, presumably pressured by deadlines and the need to get stuff out every day, take a press release from some institution (think tank, etc) and essentially summarise/paraphrase it as if it is knowledge.

The lack of critical scrutiny of the information and the willingness to merely ‘disseminate’ it further is wilful in my view.

The BBC Report acknowledges this sort of problem:

In the period of this review, it particularly affected debt. Some journalists seem to feel instinctively that debt is simply bad, full stop, and don’t appear to realise this can be contested and contestable.

I would broaden that critique to encompass almost all commentary that we see on our public broadcasters.

Sensationalising headlines and claims such as:

1. The deficit black hole.

2. Maxing out credit cards.

3. eye watering government debt.

and all the loaded language that regularly is broadcast in one way or another by our national broadcasting institutions.

The BBC Report noted the “temptation to hype” to keep the BBC audience from boredom is an example of impartiality.

But it is again also implicitly accepting a particularly paradigmic construction which is also the problem.

The ‘black hole’ terminology and its ilk is explicitly designed by mainstream economists to elicit a sense of stress, of panic, or urgency.

Black holes are dangerous, right!

When journalists then adopt this terminology – and they do it regularly in their written and oral reporting – then they become part of the ideological agenda set by the mainstream economics academy, which then serves particular ideological agendas over others.

The BBC Report also notes that:

Too often, it’s not clear from a report that fiscal policy decisions are also political choices; they’re not inevitable, it’s just that governments like to present them that way. The language of necessity takes subtle forms; if the BBC adopts it, it can sound perilously close to policy endorsement.

How often have you heard (or read) a journalist reporting that the ‘government must now focus on budget repair’?

The language and construction has two problems:

1. The problem identified by the BBC report in the previous quote.

2. The problem with the concept of ‘budget repair’, which is a nonsensical term that implies that any deficit is problematic and ‘repair’ means heading back to surplus, without any additional context being provided (such as the spending and saving decisions of the non-government sector).

Again, the problem I identify is broader than the one the BBC report focuses on.

The BBC Report also highlights the state of ignorance among the BBC audience:

We were disturbed by how many people said they didn’t understand the coverage. In our audience research, most had no comment about impartiality on fiscal policy because they didn’t know what the stories meant …

So the issue is accessibility as well as message.

Having a reporter who doesn’t understand the issue themselves attempt to interview some ‘expert’ is usually a train wreck.

I have watched countless interviews, where the journalist (some very highly regarded ones) repeatedly question a politician, thinking they are building to the ‘gotcha’ moment which will bring them celebrity, when all they are doing is perpetuating the fiction.

Questions like ‘you are going to have increase taxes aren’t you to pay for that?’ repeated ad nausea during an interview with a politician who doesn’t want to talk about taxes at all, just leave the audience with a simple message – government spending uses our taxes and we resent it.

It might appear to be ‘hard hitting’ and all the other terms used to describe these combative style interchanges but from my perspective all that is achieved is that audience has the fictional world of mainstream macroeconomics reinforced.

The BBC Report was trying to find “evidence that BBC coverage of fiscal policy is overall too left or right” when the real bias is the presumption that a currency-issuing government such as the British government is financially constrained and all the fictional logic than then flows from that.

Even if the coverage is neutral to ‘left or right’, the damage is done by what is implicit – it impacts on the type of questions asked in interviews, in the words and metaphors that are used in the reporting and more.

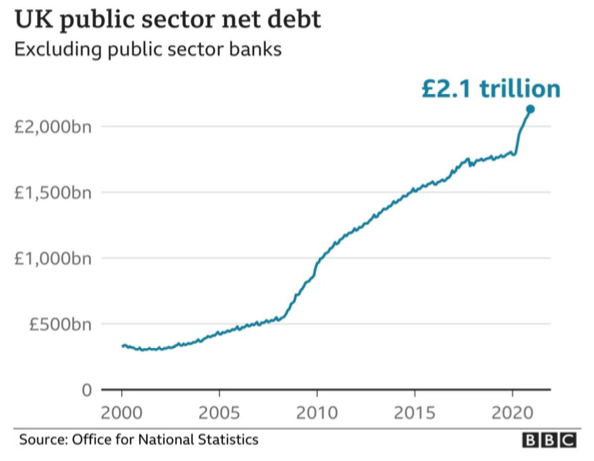

The BBC Report presents an example derived from ONS data on public sector net debt (I republish their graph (from page 7)).

They note that the graph is just factual – so what is the problem? Their reply to that question is:

The problem is there are different ways of framing them.

Yes, but the BBC Report misses the essential point in questioning various aspects of the graph because their framing just reinforces the neoliberal bias:

1. Is the graph “adjusted for inflation” – without relating it to real resource availability.

2. “£s alone don’t tell you how serious a debt is unless you also know about the resources to finance it” – implying that the debt might be serious under some ‘financing’ options.

3. “If national income grows, which it usually does, the same sum of debt will become a smaller percentage of it and generally less worrying” – implying that as some level is it worrying.

4. “the state can usually cope with more debt as it grows richer, just like you” – the household budget analogy, flawed at the most elemental level.

They go on to reinforce the household budget analogy (for example, why is 100 per cent public debt ratio a problem when “many of us could borrow from a bank or building society for a house” 4.5 times that much).

Again, debt “can be ruinous for countries as for people”.

The real problem as I see it is that no reporter ever points out that the national debt is just past fiscal deficits that have not yet been fully taxed away – leaving net financial assets in the non-government sector, which provides the wherewithal for that sector to buy public bonds as a way of diversifying their wealth portfolio.

So the funds to buy the debt come from government.

Have you ever heard anyone on the BBC explain that reality?

That is where the biased framing comes from.

We are trained to think of public debt in the same way we think of our own mortgage or credit card.

And the BBC perpetuate that flawed reasoning.

The BBC Report does have a not on “household analogies” and states:

That states don’t tend to retire or die, or pay off their debts entirely, is one way national debt is not like household or personal debt, not like a credit card for example …

Which misses the point really.

The state is the currency issuer, the household the currency user.

One has a financial constraint, the other can never be so constrained.

Once you understand that then the questions you ask and the answers you accept become vastly different.

It is not that the states “don’t tend to retire or die, or pay off their debts entirely”.

That is true but not the fundamental point of difference.

Conclusion

There is a lot more in the BBC Report that is very interesting but I have written enough today.

My overall reaction is that the Investigators themselves cannot really see through the mainstream smog – they nearly do – but leave the reader uneducated as to the real source of bias in our public reporting.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.