Last Monday, I wrote about the global need for us to abandon meat production for food, and, instead take up plant-based diets. Many people interpreted that argument as a personal attack on their dietary freedom, which indicates they fell into a fallacy of composition trap and declined to see the global issue. As part of my series on the Degrowth agenda, the other aspect about food which is important is that we have a propensity to produce too much food and distribute what we produce unfairly. I will deal with the distributional issues in another post. Today, I want to talk about the over-abundance of food in nations which means too much land, water and other resources is devoted to its production with commensurate negative environmental consequences. One manifestation of that phenomenon is food loss and food waste, which are different terms for the segment of the food supply chain where wastage occurs. If we are serious about dealing with the environmental disaster then we have to eliminate or dramatically reduce wastage. This will require significant investments in some nations to improve storage etc and a dramatic change in other nations in terms of attitudes to aesthetics, packaging, and more.

As I learn more about the Japanese language, there is a term – もったいない (Mottainai) – that has become familiar to me.

It has multiple meanings depending on context, which is a common thing in the language (Source).

It can mean simply ‘wasteful’.

It is also taken to mean ‘more than one deserves, unworthy’.

Or ‘impious, profane, sacrilegious’.

In the context of this blog post, it is a commonplace term that environmentalists in Japan use to promote their environmental agenda (the ‘3R loop’ – see below).

I used to read the magazine – Look Japan – which was an English-language publication about Japanese matters that allowed me to understand Japanese society a bit.

I was very interested in Japan for two reasons:

1. I grew up in a household that was hostile to Japanese culture, as a result of the experiences of my parents in the Second World War. As a rebellious child I wanted to reject generational type stereotypes and instead try to understand events within the historical context.

That approach certainly didn’t please my father.

2. Later, when the massive property bubble burst in 1991, and I had already begun my academic career, I was fascinated to understand how the government and its central bank handled the crisis and prevented a major rise in unemployment.

So, English-language sources of information were crucial, given the absence of ‘Google translate’ at the time.

The magazine disappeared from the library in about 2004 from memory.

It was a monthly magazine and in its November 2002 edition there was an article – Restyling Japan: Revival of the “Mottainai” Spirit – which discussed a recently released Japanese government ‘White Paper on the Recycling Society’, designed to:

… to help end the vicious circle of mass production, mass consumption and mass disposal.

The article was about a ‘hospital for toys’ and the repair culture for broken toys that had arisen to reduce wastage and allows toys to be recycled or their use continued.

In that article they extend the meaning of ‘mottainai’:

… which loosely means “wasteful” but in its full sense conveys a feeling of awe and appreciation for the gifts of nature or the sincere conduct of other people. There is a trait among Japanese to try to use something for its entire effective life or continue to use it by repairing it. In this caring culture, people will endeavor to find new homes for possessions they no longer need. The “mottainai” principle extends to the dinner table, where many consider it rude to leave even a single grain of rice in the bowl. The concern is that this traditional trait may be lost.

I wrote about this topic in this blog post – The mass consumption era and the rise of neo-liberalism (January 7, 2016)

When I was working in Kyoto last year I discovered a massive packaging and food waste problem exists in Japan.

I wrote about it in this post – Kyoto Report No. 2 (October 18, 2022).

When I learned more about this wastage, I thought back to the ‘White Paper on the Recycling Society’ that the Japanese government had released in 2002.

I had also become familiar with the so-called ‘3R Loop’, which the Japanese government had started promoting – ‘Reduce, Reuse, and Recyle’.

The Ministry of the Environment released a White Paper in 2006 on this – Sweeping Policy Reform Towards a ‘Sound Material-Cycle Society’ Starting from Japan and Spreading over the entire Globe – The ‘3R’ Loop connecting Japan with other Countries.

The ‘3R movement’ is an intrinsic part of the discussion about ‘mottainai’.

However, the juxtaposition between these policy developments in the early 2000s and what I saw in 2022 on the ground created a curiosity.

Why are the Japanese obsessed with over-packaging everything and why do they have relatively high food wastage (the two are linked to the high value that the culture places on ‘freshness’) when they also have the concept of mottainai embedded in their cultural traditions etc.

That tension is an on-going research task for me.

Degrowth and food wastage

While it is one thing to radically change our food production techniques and composition, and as I explained in last week’s blog post – Degrowth, food and agriculture – Part 6 (February 13, 2023) – we can also ease pressure on the natural environment by consuming less through minimising wastage.

Why doesn’t the mottenai concept extend to food?

Well it sort of does in the sense that it is culturally uncool in Japan to leave food on one’s plate.

But at the same time there is massive food wastage due to the freshness anxiety.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) provides a – Food Loss and Waste Database – which “contains data and information from openly accessible databases, reports and studies measuring food loss and waste across food products, stages of the value chain, and geographical areas”.

It is a valuable resource for tracking food wastage behaviour across the globe.

It is very detailed – by product, by nation, etc.

You can learn more about this from the – The State of Food and Agriculture 2019 – report published by the FAO.

‘Food loss’ refers to wastage up to the retail level, while ‘Food waste’ covers losses at the retail and consumption level.

Losses occur due to harvesting difficulties, storage inadequacy, poor trade logistics etc.

In terms of ‘waste’, the problem of “shelf life, the need for food to meet asethetic standards in terms of colour, shape, and size” are important factors.

Labelling confusion also impacts – “best before and use by” – and poor home storage techniques.

The FAO argues that “business” and “economic” cases have to be made before “food loss and waste reduction” will be taken seriously.

This is the problem – if we see things in terms of private costs and benefits – and privilege private profit-making as the allocative model then clearly we will make different decisions than if we broaden our goals to embrace, for example, the principle of mottenai – the cultural repulsion towards wastage.

The fact that private profit is the dominant motivator is exactly why we have this wastage problem.

Even the FAO argue that there is a:

… broader case for reducing food loss and waste … [which] … looks beyond the business case to include gains that society can reap but which individual actors may not take into account.

These gains include “improved food security and nutrition” and “mitigation of environmental impacts of losing and wasting food, in particular in terms of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as well as lowering pressure on land and water resources.”

These gains will not be realised by a reliance on the ‘market’, which means that government policy intervention is required.

Intervention can “raise awareness of the benefits of reducing food loss and waste” and also impose sanctions or incentives to reduce wastage.

In terms of the environmental gains merely reducing wastage may increase supply and reduce prices, which, in turn, might increase demand.

Which defeats the purpose.

Policies need to reduce the “pressures on land” – “meat and animal products … account for 60 per cent of the land footprint associated with food loss and waste” – which is one reason for transitioning away from these products.

But, the largest GHG emissions “associated with food loss and waste” come from cereals and pulses, usually because of poor farming techniques.

The research evidence is that:

… other types of interventions result in larger reductions in some environmental impacts, e.g. improved agricultural production methods and dietary changes

So a shift to more localised production of plant food, less animal consumption and permaculture techniques are clearly required.

One of the UN – Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Indicators – relates to “Global Food Loss and Waste” and the UN publish a ‘Food Loss’ and ‘Food Waste Index’ to measure this type of wastage.

The UN note that:

The global percentage of food lost after harvesting at the farm, transport, storage, wholesale and processing levels is estimated at 13 percent in 2016 and 13.3 percent in 2020.

The UN Environment Programme publishes their – UNEP Food Waste Index Report 2021 (most recent) – which helps us understand the scale of the problem.

8-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions are associated with food that is not consumed.

Reducing food waste at retail, food service and household level can provide multi-faceted benefits for both people and the planet.

In the Report, we learn that:

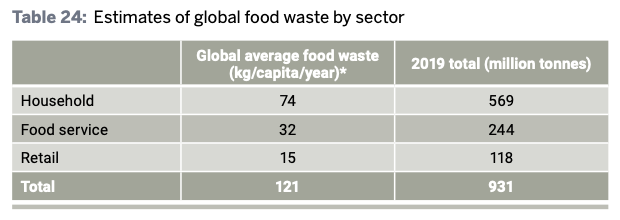

1. “around 931 million tonnes of food waste was generated in 2019, 61 per cent of which came from households, 26 per cent from food service and 13 per cent from retail. This suggests that 17 per cent of total global food production may be wasted (11 per cent in households, 5 per cent in food service and 2 per cent in retail).”

2. “Household per capita food waste generation is found to be broadly similar across country income groups, suggesting that action on food waste

is equally relevant in high, upper‐middle and lower‐middle income countries” – early studies on food waste had considered food wastage to be a problem of affluence but the latest data shows it is more generalised than that.

3. “Previous estimates of consumer food waste significantly underestimated its scale … [now we know that] … food waste at consumer level (household and food service) appears to be more than twice the previous FAO estimate”.

The irony is that while there is a lot of noise about emission reductions and lots of meetings, the major global agreements (such as the Paris Agreement) do not “mention food waste” despite the significant climate impacts that are now known.

There is also a distributional issue.

The Report estimates that while tonnes of produced food is wasted each year, there were still:

… 690 million people were hungry in 2019 … With a staggering 3 billion people that cannot afford a healthy diet

While data limitations are rife, the UN Report provides this table (Table 24) to summarise the global waste by source.

So, of the 931 million tonnes of food produced that goes to waste, 61 per cent is in the household, 26 per cent from food services and 13 per cent from retail.

In other words, there is wastage all along the supply chain that can be reduced.

The Report provides an accompanying – Database – which allows researchers to drill down into the sources of food wastage.

Back to Japan

Some points to note:

1. Japan’s imported food dependency means that so-called “food mileage” indicator (amount times distance from where produced) is relatively high – so where possible localism is best because it reduces ‘food kilometres’.

For reference, consult this report from the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries – 「フード・マイレージ」について 「フード・マイレージ」について (About Food Mileage).

2. They are reforming their ‘best-before date’ policies which relative to the rest of the world provide a very short period after production before expiry.

3. They are reforming the so-called ‘one-third rule’ (replacing with a ‘one-half’ rule) which relates to the gap between “production and best-before dates” (Source).

4. In July 2021, the Japanese Finance Corporation conducted a – Consumer Trend Survey – which showed more companies are introducing policies to reduce food loss.

It also showed that 58.8 per cent of consumers were now “making efforts to reduce food loss”, and increase of 9 points over the 2019 Survey result.

Younger Japanese were concerned about “food costs”, whereas older respondents said that “throwing away food was against their conscience”.

Younger respondents also were concerned about the environment.

So progress.

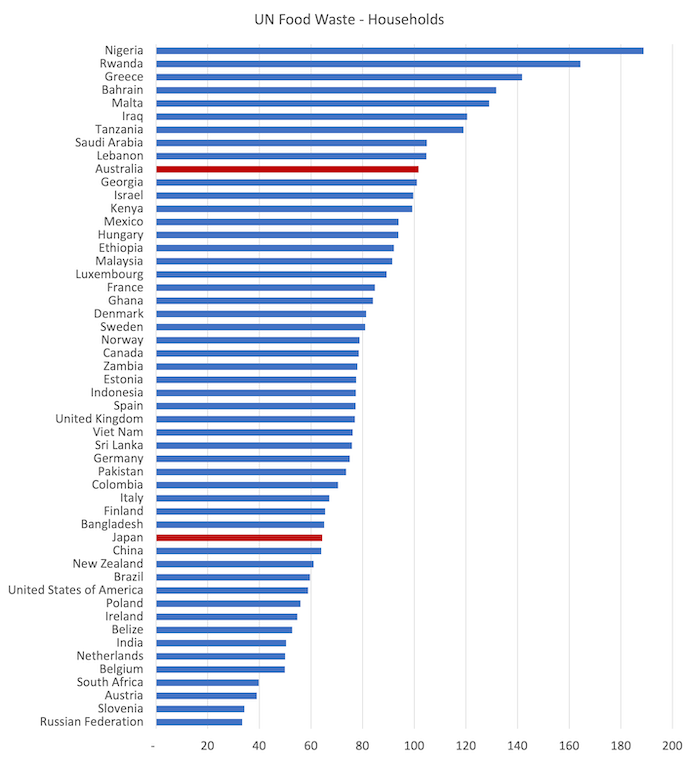

I wondered how Japan compared with other nations in this regard.

The following graph shows food loss (kg/capita/year) estimates for households from the UN data for nations were there is ‘high’ or ‘medium’ confidence in the quality of the data.

The average for this cohort was 82 in 2021.

The highest offenders probably lack proper storage and transport facilities.

But there is no excuse for Australia (one of the wealthiest nations) to be so far above average.

Japan, despite the attention of the Japanese government, is well below the average wastage.

Conclusion

I see this as a major issue in the degrowth agenda.

It is also linked to obesity and overeating.

So a good place for governments to start in this regard is to introduce massive education programs designed to curb food wastage.

In Australia, this issue is more or less invisible in the policy space.

More needs to be done.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.