Financial advisors are generally required to abide by ethical standards, such as the duty to act in a client’s best interests when giving financial advice. Advisors who attain the CFP marks are held to even higher standards, though, with all CFP certificants required to adopt CFP Board’s own more-stringent Code of Ethics and Standards of Conduct. It would stand to reason, then, that advisors who are CFP certificants would be less likely to engage in professional misconduct than their non-CFP counterparts, since they voluntarily adopt this higher standard of ethical conduct in order to use the CFP mark.

A forthcoming study by Jeff Camarda et al. in Journal of Financial Regulation, however, concludes the opposite. The paper’s authors state that based on their review of publicly available data, CFP certificants had higher levels of advisor-related misconduct than non-CFPs. Which, if true, would be a surprising and concerning revelation, particularly for CFP certificant advisors (as well as for CFP Board itself) who view the CFP marks as the ‘gold standard’ of financial planning – in large part because of the higher standards of conduct required – because of the risk to their reputation should those marks instead be associated with a higher likelihood of misconduct.

But a closer look at the data used in the study reveals issues with the authors’ conclusions. The paper examines advisory-related misconduct data for more than 625,000 FINRA-registered individuals (specifically those who have filed Form U4) and compares the rates of misconduct between CFP and non-CFP certificants. The issue, however, is that not everyone who files Form U4 is an advisor – many assistants, executives, researchers, traders, and other types of professionals are also required to register with FINRA. In fact, according to industry research, there were only about 292,000 financial advisors in total as of 2020, meaning it’s possible that less than half of the individuals used in the study were actually financial advisors. Meanwhile, the vast majority of CFP certificants are financial advisors – meaning it’s hardly surprising that CFP certificants were found to be more likely to have histories of advisory-related misconduct than other U4 filers, simply because they were much more likely to be financial advisors in the first place!

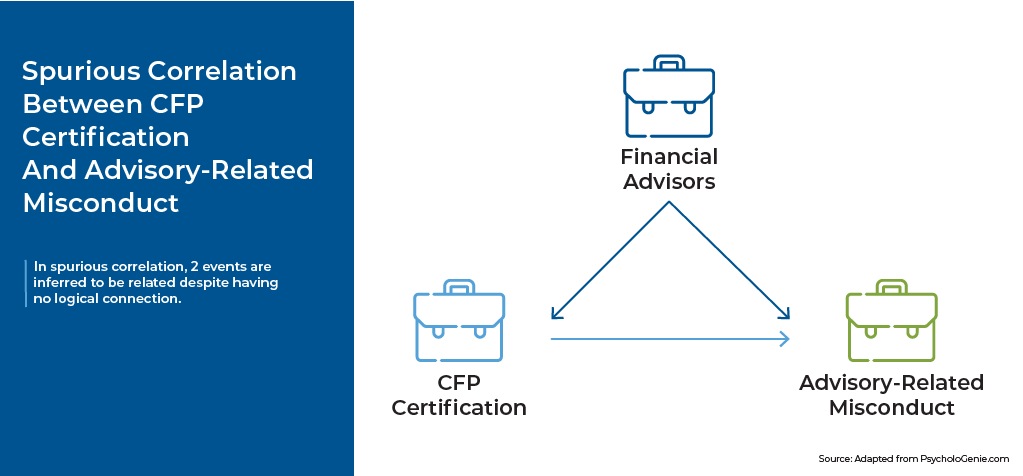

Previous research by Derek Tharp et al. attempted to identify actual financial advisors and control for other non-certification-related factors, and found (among a smaller sample size) that CFP certificants were actually less likely to have engaged in advisory-related misconduct than non-CFP professionals. Which highlights a key issue in misconduct-related research, which is that researchers’ conclusions are only as trustworthy as the data that goes into the study. Because when similar research attempts to explore rates of misconduct using other variables – such as firm size, fee models, client types, etc. – without being careful to search for unrelated factors in the data that could inadvertently skew the outcome, it can result in similarly ‘surprising’ conclusions that are really just a reflection of spurious relationships based on poor data quality rather than reality.

The key point is that even – or especially – when looking at research based on big data, it’s still important to rely on logic when interpreting the results. Sound research may certainly produce conclusions that go against intuition, but when such surprising results do occur – such as finding that CFP certificants commit misconduct at higher rates despite voluntarily adopting a higher standard of conduct than non-CFPs – it’s often the case (after a closer look at the data) that the more logical conclusion is the correct one.