Today, I am over committed and have to travel some, and, luckily, we have a guest blogger in the guise of Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University who has been one of my regular research colleagues over a long period of time. He indicated that he would like to contribute occasionally and that provides some diversity of voice although the focus remains on advancing our understanding of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and its applications. Today he is going to talk about the current concerns about the provision of regional banking services.

Anyway, over to Scott.

The banks are screwing our communities and it is time to do something

Over the past month or so we have once again witnessed the ugly truth about the Australian banking sector.

The four big banks, who serve a large proportion of the Australian population, have been out and about trumpeting their annual performance.

We have been hit with headlines such as:

1. Commonwealth Bank profit jumps to $5.15bn amid rising interest rates (February 15, 2023).

2. Banks hurtle to record profits turbocharged by Reserve Bank pandemic help (February 21, 2023).

3. Another of big four banks posts record profits in wake of interest rate hikes (February 16, 2023).

The Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia was clearly impressed with the performance of the banks when he told the government at the presentation of the Annual Report 2021-22, that it was (Source):

… important in the long term to have ‘strong’ banks that are turning a profit, even though it may be hard to hear for people in the grips of skyrocketing mortgage repayments.

And more galling, he went on to say that:

I know it’s hard for people to accept when they’re suffering … but the country is better off having strong, resilient banks that can provide the financial services that we need.

From our politicians, there was barely a peep, except for some rumblings about the bank’s unwillingness to pass higher interest rates onto deposit holders and a shallow call from the Federal Treasurer for the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) (Source):

… to look into how banks set interest rates for savers, including differences in interest rate increases between bank deposits and home loans.

Apparently, he was driven to this decision because:

… he understands why Australians are ‘furious’ with banks that have raised mortgages but not passed on higher interest rates to deposit holders.

Of course, there will nothing done.

The Royal Commission in Banking recently found they lied to, cheated and stole funds from their clients, but nothing substantial has been done about any of that.

The big four banks meanwhile talk about the negative impacts of borrowing costs and the challenging business environment using typically meaningless phrases like ‘significant economic headwinds’ and off-setting criticism by talking up their community engagement.

According to one of our largest privately owned banks, which used to be fully owned by the public (Source):

CommBank community grants help ‘take the pressure off’ Australian charities

(For non-Australian readers, “CommBank” is short for the Commonwealth Bank, which was once government owned and was privatised by the Australian government between 1991 and 1996).

So this is the typical ‘social responsibility’ whitewash that marketing spin doctors in corporations pump out on a daily basis.

Look how nice we are to our communities!

Typical neo-liberal profit-driven stuff.

They pay huge executive salaries and make a profit for shareholders and use diversion tactics to shift people’s attention away from the issues.

The broader community is seeing through the bank’s diversionary tactics

From the average punter there was the expected and justified hue and cry about the greed of the banks with social media lit up with complaints about profit-gouging from the ridiculous and greedy banks.

The banks claim they are helping their local communities, but the reality is that their business model is designed to screw every last cent out of the consumers they entice through their doors.

Alongside the angst about the bank’s profits has been the growing outrage about the removal of services and branches from local communities.

The general flavour of these concerns can be seen in the video from the Australian Broadcasting Commision which was published on March 2, 2023 under the title: Banks told to put people before profits amid regional closures.

There have been a myriad of articles recently in the media about these issues, including, for example:

1. Westpac to close branches despite Senate inquiry plea (February 14, 2023).

2. A third of the nation’s bank branches have shut in the past five years — for people in the country, that’s a huge problem (March 2, 2023).

3. Regional bank closures have SA locals buying safes, scared for safety as MP calls for banks to do ‘right thing’ (February 22, 2023).

The general vibe is that the banks are screwing over communities across the country!

The concern about regional bank closures has emerged in light of the release of data by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) and some subsequent media attention.

For context APRA

… is an independent statutory authority that supervises institutions across banking, insurance and superannuation and promotes financial system stability in Australia.

As part of my broader data collection activities, I have recently investigated APRA’s Authorised Deposit-Taking Institutions Point of Presence data set, which is available – HERE).

The data set is essentially a count of banking services-point of presence- across Australia presented at an aggregated geographically level.

APRA collects this data as part of its usual operations, and although the accuracy of the data has been questioned it does make for some interesting data mining.

The data that has been causing the most anguish relates to the figures at broad metropolitan and regional/rural levels, also known as remoteness levels.

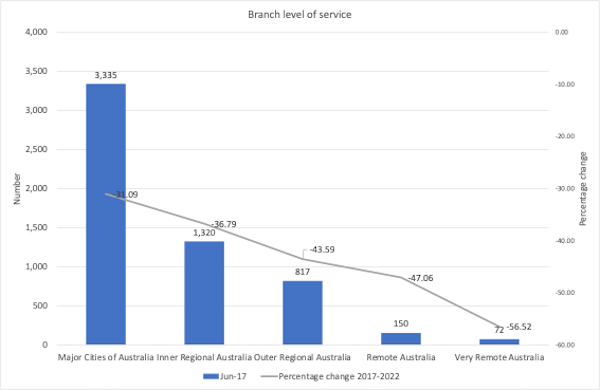

Eyeballing the data collated between 2017 and 2022 provides a relatively clear picture of what has been happening in recent years.

In a nutshell, the number of bank branches has fallen significantly across the board, especially in non-metropolitan regions.

So, as has been well reported, the banks are slowly withdrawing services from communities, especially in the regions.

This data got me thinking about how these patterns might be reflected in other measures of regional social and economic performance.

Some regular readers might recall that Bill and I have recently received significant three-year funding for a large Australian Research Council project looking at how regions across Australia can be differentiated in terms of employment and economic resilience.

The project uses the economic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic as a backdrop.

The genesis of the project, which has taken a couple of years to come into being (such is the nature of research funding in academia), can be seen in this blog post – Using a regional lens reveals the uneven impact of the COVID employment crash (February 11, 2021).

We also published a pilot paper in the Australasian Journal of Regional Studies in 2022 – see the blog post with the embedded article: – Regional employment resilience capacity during Australia’s early covid-19 public health response: An analysis of the payroll jobs index data series (March 15, 2023).

You can download the published paper via that page.

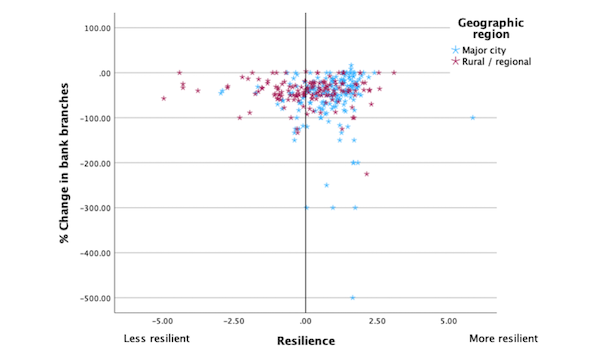

This pilot work only measures resilience during the early stages of the COVID-19 economic slowdown but adding the banking data to our data on regional resilience allows us to consider any patterns in the data.

The following graph plots the percentage change in bank branches by employment resilience, with the data points divided between metropolitan and rural/ regional communities.

Although the patterns are not yet 100 per cent clear, the take-home message from this graph would appear to be that:

- Metropolitan regions were relatively more resilient (a finding identified in our paper)

- Although bank branch closures impacted communities across the board, the relative over-representation of rural/regional communities in the less resilient category suggests that these places will be impacted far more due to the removal of face-to-face banking services in their less resilient local economies.

How these patterns have played out in the longer term will be an interesting piece of our ongoing research puzzle, but the early signs certainly are not good.

The decline in regional banking has been on a slow-burn since the 1980s when the banking sector was deregulated.

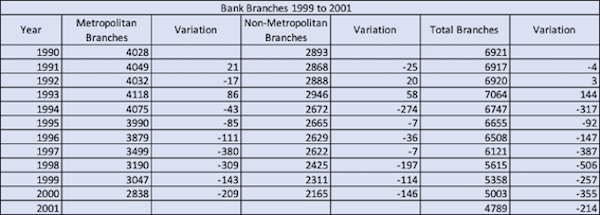

The data in the table is taken from a 2004 Inquiry conducted by the Australian Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services – Money Matters in the Bush: Inquiry into the Level of Banking and Financial Services in Rural, Regional and Remote Areas of Australia.

Chapter 2 – Bank branch closures in rural, regional and remote Australia – produced Table 2.1, which we reproduce below:

The accompanying discussion noted that:

The above statistics show that the fall in the number of branches is most significant in metropolitan areas. Even so, the loss in non-metropolitan areas has been substantial. Of the more than 2,000 bank branches that have closed since June 1993 well over 750 were in non-metropolitan areas. Furthermore, the loss of full banking services as provided by a bank branch can be felt most keenly in rural, regional and remote Australia where in some cases the closure of a branch has left communities without a banking facility in their district.

So we knew in 2004 that this was becoming a problem yet nothing has been done about it.

Surely the fact that banks have been reducing services consistently over time would have raised the ire of most people who engage with the modern banking system. Given it is still going on, apparently not.

In academic circles sociologists, geographers and others have talked about the impact of declining service provision in regional communities for years.

Yet mainstream economists have only talked about efficient markets and optimal outcomes for all.

The withdrawal of services such as banks from regional Australia has been linked to the social and economic erosion of community life in these places.

In this 2008 paper published in the gernal Australian Geographical Studies (October 9, 2008) – Financial Exclusion in Rural and Remote New South Wales, Australia: a Geography of Bank Branch Rationalisation, 1981–98 (paywalled) – the authors state in their introduction:

The provision of financial services in rural Australia is a significant public policy issue, reflected in the high level of media and political interest in the recent spate of branch closures.

Sounds familiar.

They also note that although the banks argued that branch closures in rural and remote locations were due to declining customer numbers, there was in fact little correlation between demographic patterns (that is, population growth or decline) and branch closures.

In fact, they find that:

… corporate-level responses to increased competition within the financial system are significantly more important in deciding rural access to banking services than local and regional population trends. Indeed, two thirds of rural localities that have lost branches had experienced healthy population growth during the study period.

Except, there is a dearth of competition in the banking sector as evidenced by their ability in the current period to gouge profits and hold deposit rates down while cashing in on the RBA interest rate hikes.

Of course, the banks run the ‘competition’ line – even today.

The reasons might have changed (less demand for cash rather than declining numbers) but the outcomes are the same.

The banks just blame it on the changing customer base or a change in preferences.

At the end of the day, the profit motive remains the number one driver and customers come second!

The government’s reaction?

It would be fair to expect that the federal government might have something meaningful to say about how banks treat communities nationwide.

But to date, the government’s modus operandi seems to follow a familiar pathway.

1. Provide the media with an inane soundbite that suggests you are going to take the issue seriously.

2. Order an inquiry.

3. Then allow the banks to return to business as usual.

We have seen this time-and-time again.

For example in the late 1990s the Liberal National Party established an inquiry into regional banking through the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, Finance and Public Administration – Regional Banking Services: Money too Far Away (March 1999)- to:

… report on alternative means of providing banking and like services in regional and remote Australia to those currently delivered through the traditional bank branch network.

The recommendations contained the usual banal list of suggestions.

The 2004 Report from the Australian Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services – Money Matters in the Bush: Inquiry into the Level of Banking and Financial Services in Rural, Regional and Remote Areas of Australia – noted above, summarised the findings of that 1999 exercise as follows:

The report strongly encouraged service providers, governments and communities to work together to develop strategies aimed at ensuring that rural and regional communities have access to the financial services they need.

What?

Business went on as usual and the political crisis at the time was ‘solved’ by claiming there had been an ‘inquiry’.

Clearly much not happened and we are back at a similar juncture.

The 2004 Inquiry, itself focused on:

- Options for making additional banking services available to rural and regional communities, including the potential for shared banking facilities;

- Options for expansion of banking facilities through non traditional channels including new technologies;

- The level of service currently available to rural and regional residents; and

- International experiences and policies designed to enhance and improve the quality of rural banking services.

Looking through the Report we read the same kinds of outcomes as the previous report with comments and recommendations including:

- The Committee believes that ensuring the provision of adequate banking and financial services to regional, rural and remote Australia is the joint responsibility of the financial services sector and government with the active involvement of the community;

- Strengthen the protocol governing branch closures by, inter alia, requiring banks when considering branch closures to consult with the community and to release a community impact statement;

- An undertaking that banks will take all reasonable measures to educate customers in the use and benefits of accessing banking services through new technologies; and

- Further, that the code will offer practical guidance on some of the measures that banks could take to ensure that they are effective in meeting this commitment.

And so it goes!

The most recent report was published on September 20, 2022 – Regional Banking Task Force – Final Report – which was the work of the Australian Treasury and the Task Force included the big banks, some peak lobby groups, who typically support the big banks, Australia Post (who want to compete but are not allowed to) and local government representatives.

Looking at the Final Task Force Report we read the same kind of comments and recommendations that were around 20 years ago.

- Banks can do more to communicate and consult with individuals and communities when closing a regional branch;

- When branches do close, alternatives like Bank@Post can assist to maintain banking services;

- It is important to maintain access to cash, which is crucial for many in regional Australia; and

- People experiencing vulnerability face particular challenges and need support in accessing banking services.

Enough is enough, no!

Sorry, there is more.

The Australian Senate has now launched an inquiry –

On February 8, 2023, the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee of the Australian Senate has launched a new inquiry into Bank closures in regional Australia = which must report by December 1, 2023.

Don’t get too excited though.

It is highly likely that the final outcome will just reflect the part outcomes.

That is, nothing of substance will emerge.

In other words, situation normal.

Why are we bothering?

The government of the day could have saved a lot of time and just changed the date on the report.

Also, let’s face it, the massively funded and lengthy – The Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry – which was established in December 2017 and published its final report on February 1, 2019 – hasn’t exactly led to any significant policy changes despite, as noted above, finding appalling and criminal behaviour of the banking sector.

If a Royal Commission doesn’t get anywhere, how can a ‘task force’ or two with the cops investigating cops, get anywhere, especially, given the political funding rules that exist in Australia – you know, the ones that allow corporations to effectively buy votes.

Ok. Time we did something about this!

Instead of tiptoeing around the issues as is currently happening, we need some meaningful action.

It is surprising that consumers put up with this type of behaviour by the banks.

Over a decade ago (May 30, 2011), the Guardian UK author Madeleine Bunting asked the question – Outrage at the banks is everywhere, so why aren’t there riots on the streets?.

Good question!

As part of discussions that Bill and I had with Noel Pearson and others looking at pursuing a Just Urgent and Sustainable Transition in Australia, it was clear that one of the pillars to guide the country’s future should be banking for the people.

In other words, a bank that has at its heart the welfare of its customers (not shareholders, directors or CEOs) and is owned by the Australian people /government.

In several early posts (following the GFC), Bill has mused about such a change to how banking services should be provided.

In his blog post from 2010 – Nationalising the banks (October 26, 2010) – he makes the point that:

… banks are public institutions given they are guaranteed by the government. But there is a tension between their public nature and the fact that the management of the banks claim their loyalty lies to their shareholders (and their own salaries) …

The solution to the tension is to socialise both the gains and losses of the banking sector. In that sense, nationalisation of the banking system is a sound principle to aim for. This would eliminate the dysfunctional, anti-social pursuit of private profit and ensure these special “public” institutions serve public purpose at all times.

In a later post – A case for public banking (July 17, 2013) – he considers research on the impact of bank shocks on investment and draws the conclusion that:

… short of bank nationalisation, the findings provide support for the creation of public banks which utilise the currency monopoly enjoyed by government to provide a more stable environment for business firms during times of crisis in the private banking sector.

So, given all the ongoing angst about banks and their lack of support for communities across the country (regional and rural communities mostly, but everywhere really) and given the government’s lack of insightful discussion around the problems, there seems to be only one smart solution – a true people’s bank!

One of the suggestions that has been doing the rounds lately has been giving Australia Post a full banking licence.

Turning the post office into a bank.

It is a win-win.

Communities will be served by a publicly owned bank and Australia Post will be able to reimagine itself, especially given the recent anxiety over its future (Source).

Returning to Bill’s post titled Nationalising the banks (October 26, 2010) – we can see the possibilities.

One option that has been suggested recently which does not involve nationalisation would aim to beat the big banks at their own game. Someone said the other day that the Australian government just has to utter two words – Australia Post. See this article (October 23, 2010) – One sure way to knock the banks into line – for more discussion on that idea.

And:

Australia Post is still a government agency and has offices in every neighbourhood. It could easily be transformed to offer banking services which would force some competition on the big four private banks.

Further, he wrote:

In this Melbourne Age article such a plan is discussed. It would “inject competition into banking, as well as providing an alternative future for Australia Post branches as their traditional postal business declined” …

the element opposing this option is that “If [Australia Post] becomes a bank, it then becomes a government-owned bank and the government would have to capitalise it”.

So what? The Australian government could always ensure there is enough capital for its bank. The reality is that the Government stands by to guarantee the private banks anyway – no major financial institution in Australia will be allowed to collapse. Given the Australia government is sovereign in its own currency it faces no financial constraints in either respect. The question is not whether the government can afford to bail out or underwrite private banking but rather whether it should.

Conclusion

It sounds like a great idea.

We only need the government to realise that they can do it without all the usual handwringing that goes along with this.

The banks will complain for sure. I can hear it now … unlevel playing field, big government interfering in the free market etc etc.

But the government isn’t beholden to the big banks and their greedy CEOs, but they are beholden to Australian communities and the people who live, work and play in them.

About time they realised that and took some action!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.